Pentagon Orders Portrait of Robert E. Lee to be Reinstalled at West Point

The Pentagon is restoring a portrait of Confederate general Robert E. Lee and has ordered its reinstallation in the library at the United States Military Academy at West Point. The painting hung in the library for 70 years before it was ordered removed as a result of a survey conducted by the Naming Commission in 2022.

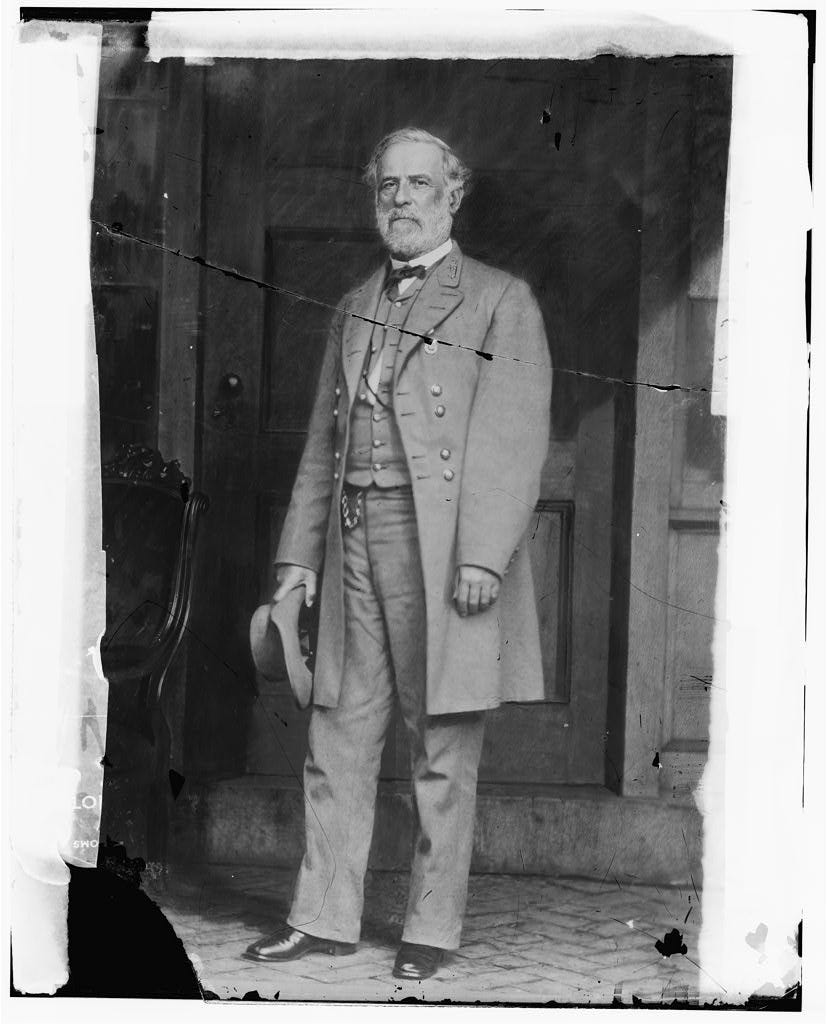

Robert E. Lee was a graduate of West Point and superintendent of the school from Sept. 1, 1852, to March 31, 1855. Lee resigned his commission in the United States Army following the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861 and took command of Virginia military forces before emerging as the Confederacy’s most successful general.

The question of whether graduates or former students at West Point deserve to be honored has divided the academy in much the same way that the subject of Confederate monuments and memorials has divided the general public. The Lee portrait is not just about a Confederate general, but about the evolution of Civil War memory at West Point.

Ty Seidule, who served as vice chair for the Naming Commission, covers this issue thoroughly in his book, Robert E. Lee and Me, which explores his own personal journey of coming to terms with the legacy of the Lost Cause and Robert E. Lee.

We should start by acknowledging that, with few exceptions, neither Lee nor the Confederacy were honored at West Point during the nineteenth century. According to Seidule:

The Civil War became the greatest crisis in the academy’s history, just as it was the greatest crisis in the nation’s history. In 1861 and 1863, Congress debated bills to close West Point completely. While those bills failed to muster a majority, they left a lasting impression. West Point refused to memorialize Lee and the men in gray in the nineteenth century because Congress and the nation blamed the academy for its graduates’ decision to fight agains the United States. (p. 185)

This began to change in the new century, following the Spanish-American War, and as an expression of sectional reconciliation. In 1902 former Confederate general James Longstreet was invited to take part in West Point’s centennial celebration, largely, according to Seidule because after the war he joined the Republican Party and “endorsed biracial politics.”

Mark your calendars! Join the Civil War Memory book group on October 19 at 8PM EST for a discussion of Elizabeth Varon’s new biography of James Longstreet. It’s a chance to discuss this book with a vibrant and smart group as well as the author, who will be joining us.

All you need to do is upgrade to a paid subscription and read the book. Hope to see you.

It was not until 1931 that West Point honored Robert E. Lee with the help of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The UDC first donated three glass cases to be filled by plaques honoring the annual winner of the Robert E. Lee prize in mathematics.

The second was a painting depicting Lee in his U.S. Army lieutenant colonel’s uniform during his tenure as superintendant of the academy.

The UDC wanted the portrait to show Lee wearing the uniform of the Confederate States of America, but the army’s chief of staff refused to countenance a portrait of Lee in gray at West Point. The army would allow Lee to be honored for his time in blue, but not yet for his leadership in a rebellion. (p. 193)

Seidule credits this change as reflecting Lee’s improved reputation among white Americans as well as Jim Crow segregation. It was no accident that the UDC’s welcome coincided with the return of the first African-American cadets in roughly fifty years.

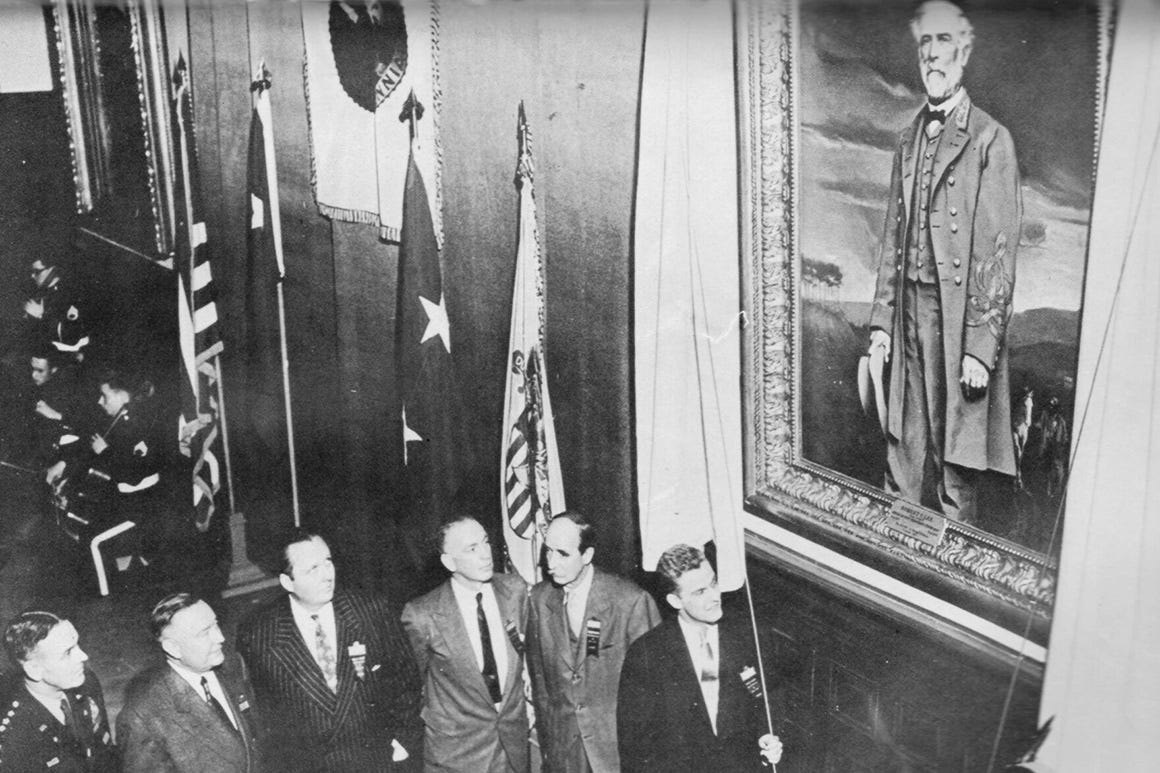

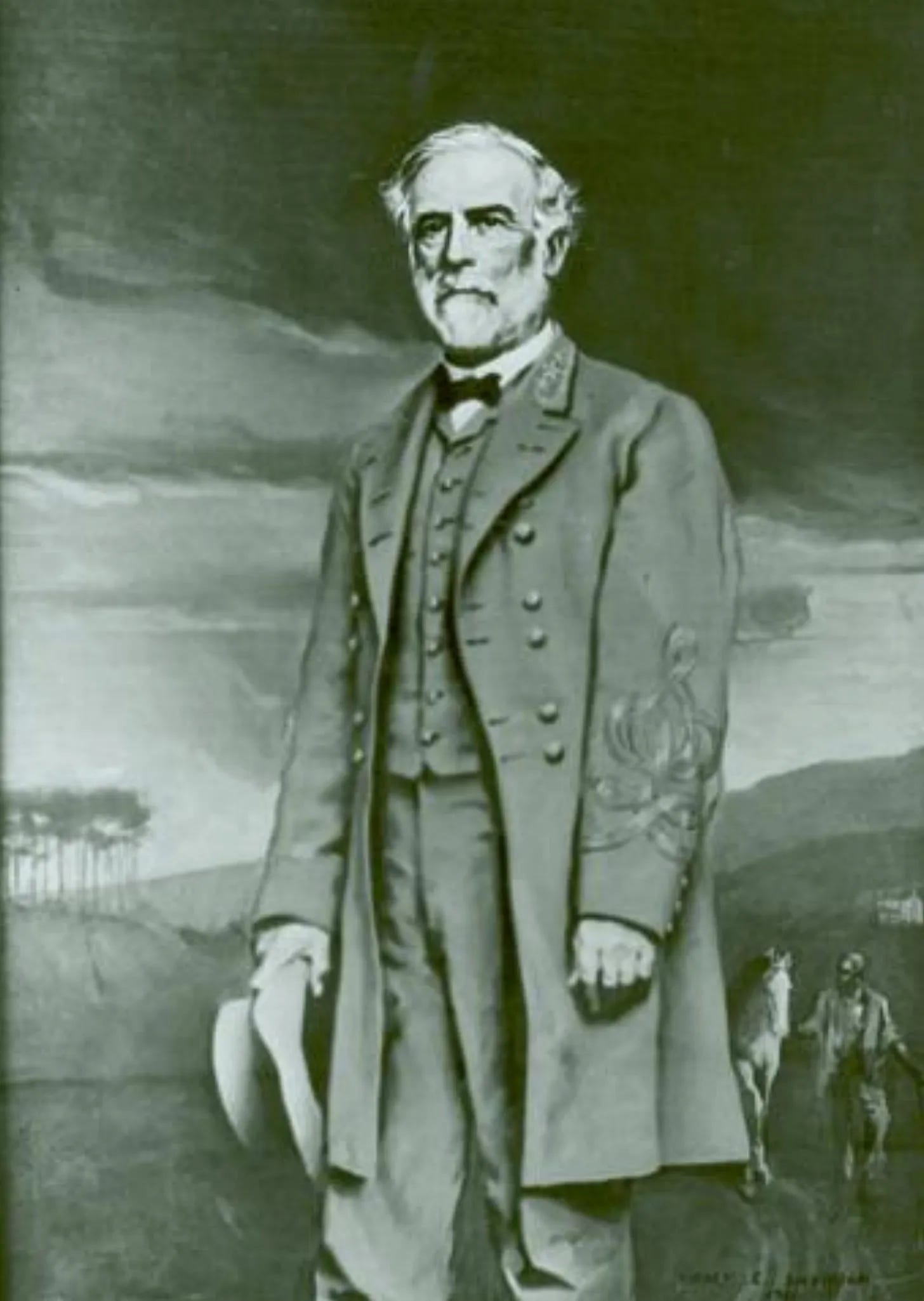

Twenty-years later the portrait that is currently in the spotlight arrived at West Point. Secretary of the Army Gordon Gray, a North Carolinan, ordered that the painting be hung to “symbolize the end of sectional difference” following World War II. The portait of Lee,” writes Seidule, “shows him resplendent in his formal gray uniform with yellow piping on the sleeve and three stars in a wreath on his collar, designating a general of the army of the Confederate States of America.” (p. 197)

Seidule argues that the placement of the painting in 1951 had everything to do with tensions over race relations.

The Korean War raged in 1950. At the same time, the army tried to slow roll implementatin of racial integration ordered by Harry Truman on July 26, 1948, in Executive Order 9981. The military has trumpeted its role in bringing racial equality to America, but the history is far more complex and less flattering. Neither uniformed leadership nor Gray wanted to integrate the army. In fact, the previous secretary of the army, Kenneth Royall, had been forced into retirement because he would not integrate quickly enough. Only the personnel requirements of the Korean War forced the army to integrate. Segregated units wasted manpower. (pp. 197-98)

Sidney Dickinson, born in Connecticut and trained in New York City, was given the commission to paint Lee. He chose to base his portrait on a photograph of Lee taken by Matthew Brady in Richmond following his surrender at Appomattox.

Interestingly, Dickinson painted African Americans while living in Alabama in 1917 and 1918, but chose not to depict them through the lens of racial stereotypes or the Lost Cause tradition.

This seems to stand in contrast to how Dickinson depicts what appears in the background of the Lee portrait to be a body servant. Seidule believes that Dickinson intended to portray “an emancipated man, not an enslaved servant…moving toward an uncertain but free future. Lee and the slave economy he fought to protect and expand diminsh like the setting sun.” (p. 199)

Seidule may be right about this, but it looks to me like the Black man is following Lee with his horse Traveller. If he is emancipated he still clearly embodies the Lost Cause trope of the “loyal slave”—the message being that even after freedom, former slaves remained loyal to their former enslavers and the Confederacy.

The painting was located in the academy’s library on a wall opposite a portrait of Ulysses S. Grant.

In addition to this story, the Trump administration has decided that Ashli Babbitt, the 35-year-old Air Force veteran, who stormed the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021 with thousands of other rioters to prevent the certification of a presidential election, deserves a military funeral. Babbitt was killed that day by police officers defending the Capitol, but since then has been transformed into a martyr by Republicans and Trump supporters.

Both Robert E. Lee and Babbitt are now being held up by our government as moral exemplars for West Point and other military academy graduates to emulate.

So much for the military’s Oath of Allegiance.

It’s important, it seems to me, to stipulate yet again that Ty Seidule is not only a retired Army brigadier general, but was also a combat Army officer for a decade before he became a PhD historian at Ohio State and moved to the West Point history department, which he eventually chaired. He has plenty of special standing, in other words, to talk about honoring Lee. I hope that Gen. Seidule considers going public about this and about that now-removed but proposed to be restored Arlington anti-reconciliation monument if those threats evolve beyond the level of Trump zealots’ dishonorable trash talk.

Portraits of traitors now. Who is next Benedict Arnold? He has some history with West Point too.