I have a friend and fellow history teacher who is working on a classroom project that asks each student to select an item to interpret for a museum about the Lost Cause. The students must also explain their choice for the exhibit. It’s a reminder of the amazing teaching that takes place in classrooms across the country each and every day and I absolutely love this idea.

Of course, she asked me to think about what I would contribute to such a project and I thought it would make for a perfect open thread post for all of you to consider. Today we are going to make our own Lost Cause museum one document and artifact at a time.

I’ve considered a number of items over the past few days, but I decided to go with something that is right in my wheel house and which brings together a number of different threads from the Lost Cause narrative.

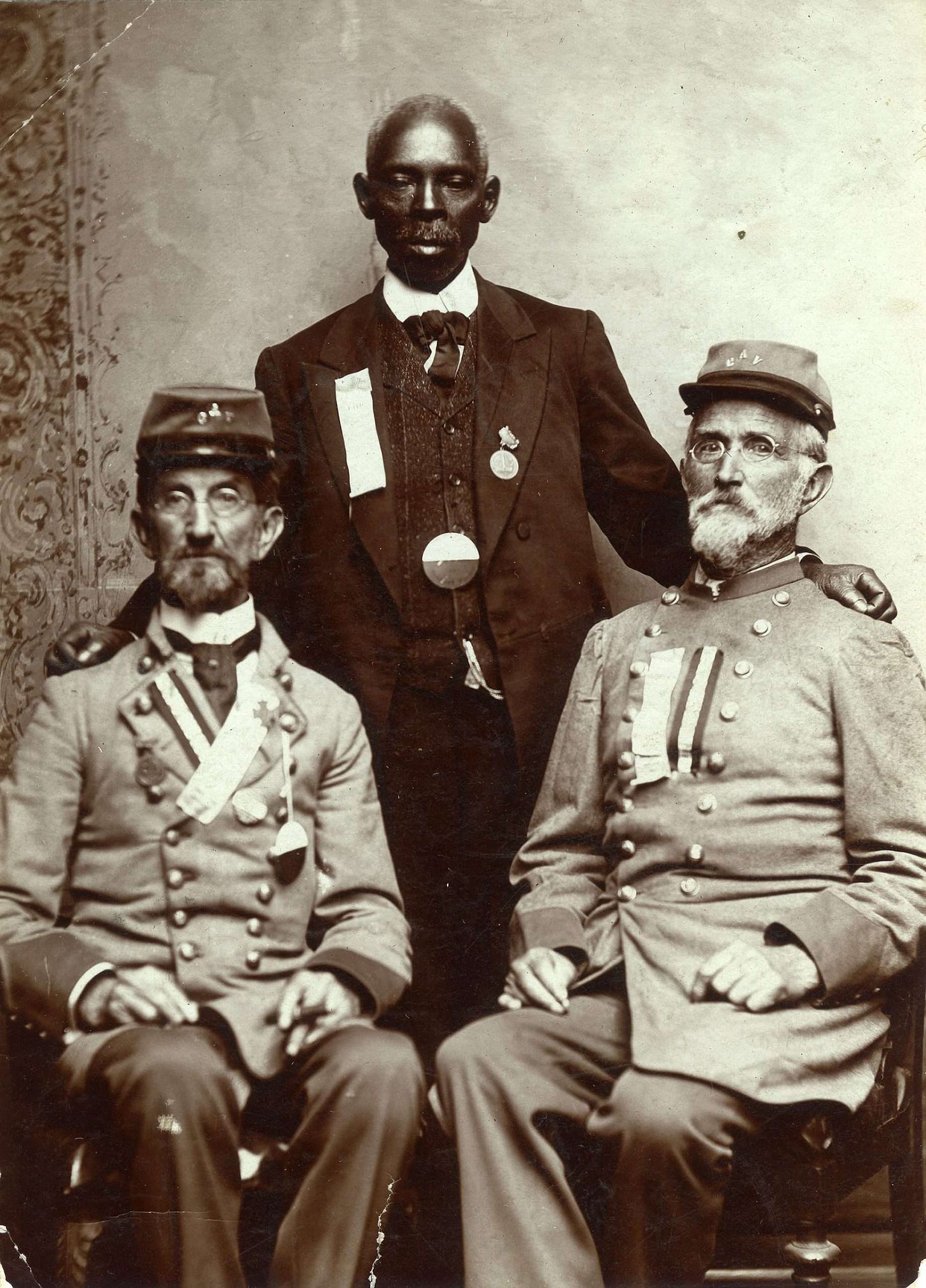

This is one of the few photographs of Confederate veterans posing alongside their former body servants. Confederate veterans were front and center in the Lost Cause narrative through the first two decades of the twentieth century. This particular photograph was likely taken during the United Confederate Veterans reunion in Richmond, Virginia in 1907.

These men were the living reminders of the antebellum South, the war years, and Reconstruction.

UCV reunions often attracted tens of thousands of people from around the country. They were not only a reminder of the past, but served as a benchmark for a new generation of white southerners who never experienced the war or the perceived threats that whites attached to Reconstruction and who would serve as a rudder for a region struggling to embrace modernity.

The African American man also plays a crucial role in this image. Virginia revised its state constitution in 1903 barring the majority of African Americans from voting. This came after a flurry of Black political activity during the years of Readjuster Party control, led by former Confederate general William Mahone.

The understanding of this man as a former “faithful slave” or body servant may have reinforced the paternalistic outlook of the former slaveholding class and former Confederates generally, but this man also performed a specific role at reunions and other veterans events for a younger generation of white southerners. The performance of these elderly men for audiences with their wartime stories of fidelity to their former masters and the Confederacy symbolized a kind of deference that white southerners expected from Black southerners as Jim Crow segregation solidified across the South.

If African Americans had always been loyal to their masters and never sought freedom, the argument went, they could continue to be relegated to second class status.

The Lost Cause was never about a dead past, but remained a potent weapon in the re-ordering of race relations following Reconstruction that lasted well into the twentieth century.

Of course, as I argue in Searching for Black Confederates, these photographs have come to prop up a modern-day version of the Lost Cause by suggesting that these images depict Black soldiers or “Black Confederates”—a term that was rarely used during and even after the war. Real Confederates would find any interpretation of this photograph, outside of the master-slave relationship, as truly bizarre and wrong-headed.

This misguided and self-serving interpretation brings into sharp relief the distinction between history and memory.

OK, what about you? What document or artifact would you like to contribute to our Lost Cause museum? And don’t forget to explain your choice.

Thanks.

I choose the book written by Dr. Hunter McGuire and George L. Christian, "The Confederate Cause and Conduct in the War Between the States" (1907). It was prepared as a History report for the Confederate Veterans of Virginia and is particularly interesting (I think) to schoolteachers as these men examined the current textbooks being used to tell the history of the Civil War and found them "replete with error and misrepresentation." McGuire's first chapter: "Slavery Not the Cause of War." I wonder how much this book actually influenced textbooks later published in Virginia.

Everything listed so far is great.

I would say that there should be a room in the museum for late 20th century Lost Cause examples, and I'd put in the center of it the General Lee car from Dukes of Hazard.

Popular culture is such an important part of Lost Cause mythology. The fact that a relatively popular TV show had a car named after Robert E Lee, with a confederate flag on its roof, and the people that owned the car and drove it were the good guys presents a perfect picture of lost cause mythology in the 70s and 80s. I know as a kid I had a matchbox car of the General Lee.

I'd also add to this room jerseys from what used to be an annual College Football bowl game - the Blue vs Gray game. This was a college football all star game that was played (usually around Christmas) between all star players from southern states vs all stars from northern states. There was often civil war imagery around the game, and it was played all the way to the early 2000s.

I'm sure there are other cultural items like these that could show the softening of attitudes toward Lost Cause mythology, but these two came to mind first. I'd argue that the prevalence of cultural items like these contributed to an attitude that embraced Shelby Foote in Ken Burns Civil War - after all, he was just a good ol' boy...