You can’t open up a major newspaper today without reading a steady stream of op-eds lamenting the end of democracy in the United States or come across a poll predicting a civil war in the next few years. There is a balm for such doom and gloom predictions: It’s called history.

This morning I caught part of an interview between Mehdi Hasan and former Republican Congressman Joe Walsh. Early on in the interview Hasan asks Walsh, “Do you worry about civil war?” Walsh offered the following in response: “The MAGA base, they're welcoming violence... Trump wants violence, MAGA wants violence. I just don't think the American people fully understand the unprecedented moment we’re in.

There is certainly much to be worried about. We can’t go a day without reading about violent incidents taking place around the country.

But “unprecedented”? Really?

The point isn’t to suggest that these are not serious problems or that we shouldn’t be addressing them. We most certainly should, but we also need to do a better job of placing them in historical context. Somehow, in this mode of thought we lose all sight of history and context.

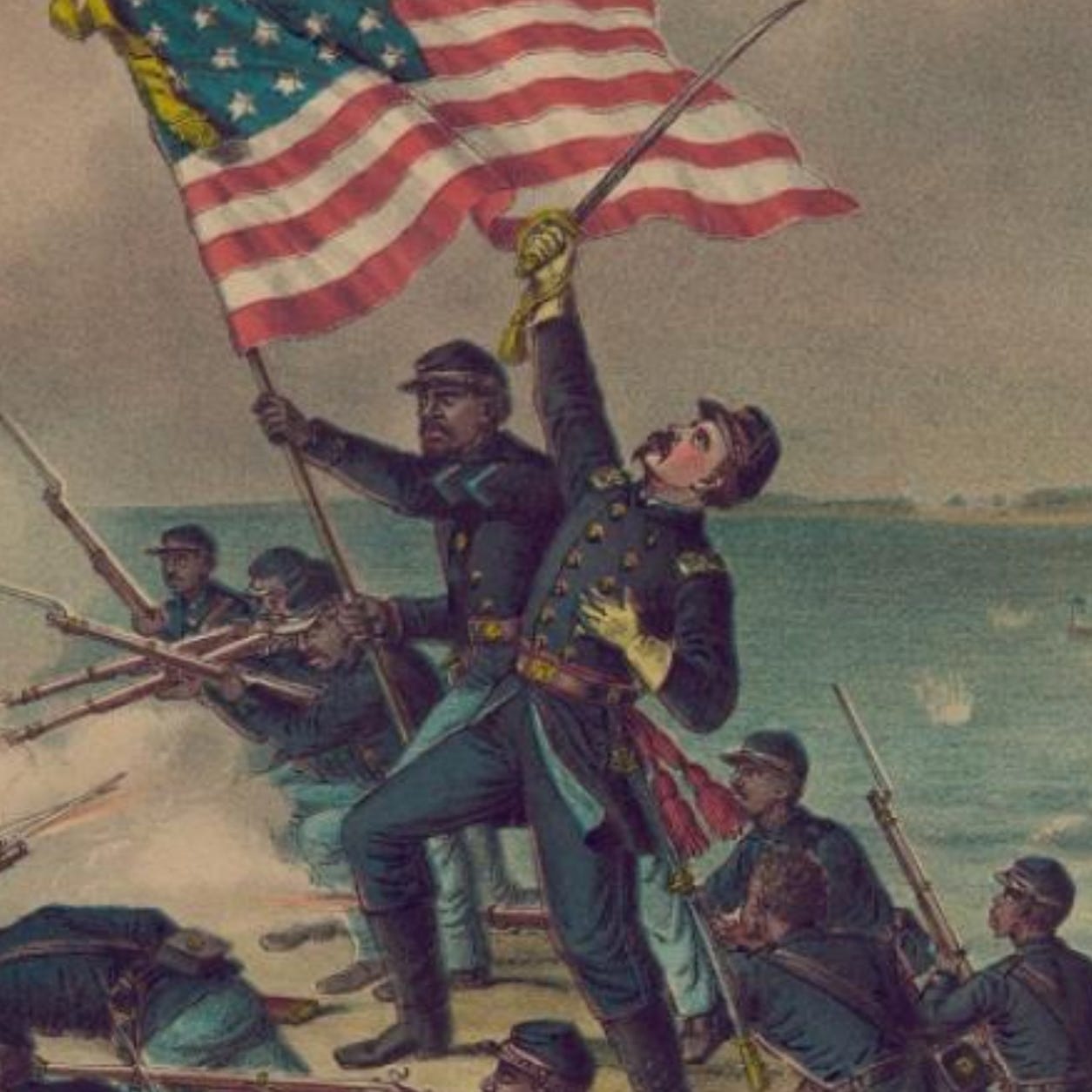

I suspect that most people who are predicting another civil war have an image in their mind of our own Civil War. Who can blame them. We are obsessed with our civil war. Arguably, no other moment in American history looms larger in our popular imagination than the Civil War, but perhaps this is exactly why we are so easily led astray.

The problem isn’t that we don’t know enough about the conditions that led to war in 1861 and which cost roughly 750,000 lives in four short years, though that is certainly lacking, it’s that we don’t seem to know anything about any other moment in our history.

The point here is that history often takes a back seat in these moments when everything appears to be in decline.

I’ve recommended Jon Grinspan’s wonderful book about the second half of the nineteenth century titled, The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865-1915, before. Grinspan tells this story through the lives of radical congressman William “Pig Iron” Kelley and his daughter, Florence Kelly. Early in the book, he writes the following:

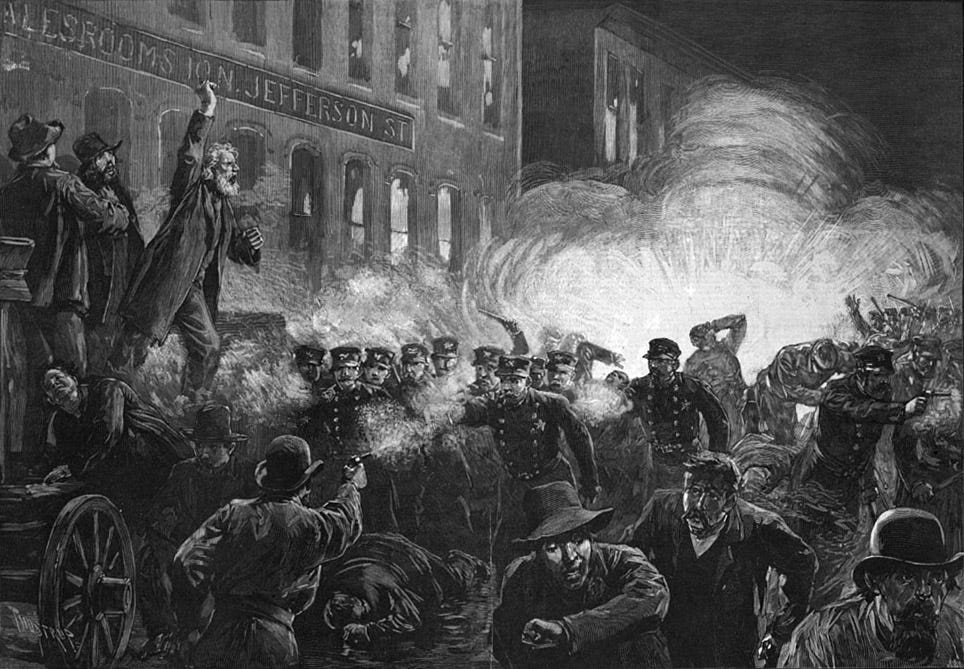

Americans claim that we are more divided than we have been since the Civil War, but forget that the lifetime after the civil War saw the loudest, roughest political campaigns in our history. From the 1860s through the early 1900s, presidential elections drew the highest turnouts ever reached, were decided by the closest margins, and witnessed the the most political violence. Racist terrorism during Reconstruction, political machines that often operated as organized crime syndicates, and the brutal suppression of labor movements made this the deadliest era in American political history. The nation experienced one impeachment, two presidential elections “won” by the loser of the popular vote, and three presidential assassinations. Control of Congress rocketed back and forth, but neither party seemed capable of tackling the systemic issues disrupting Americans’ lives. Driving it all, a tribal partisanship captivated the public, folding racial, ethnic, and religious identities into two warring hosts. (p. x)

According to Grinspan, we are not living through unprecedented times. “It’s not that our problems are the same as those of the late nineteenth century—often they are strikingly different—but that the era in between was so unusual.” (p. xii)

Grinspan offers a vantage point from which we can look more closely at how a period that witnessed a certain amount of progress on various fronts came about. More importantly, it is a reminder that nothing is inevitable.

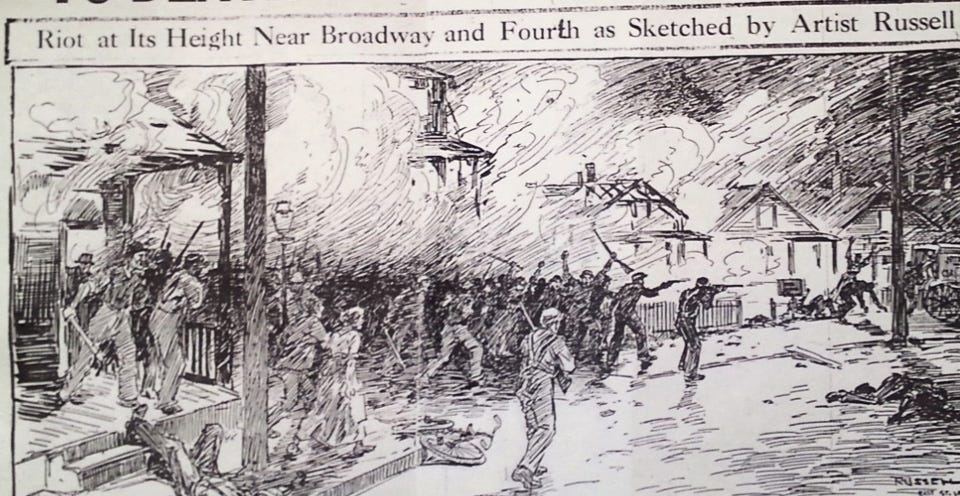

It’s a reminder that our history is filled with moments of intense violence, much of it racial such as the East St. Louis massacre in July 1917 and the Tulsa race massacre just a few years later in 1921.

Spend some time and read about the intense violence directed at Chinese immigrants in California beginning in the 1850s and culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Michael Willrich’s new book, American Anarchy: The Epic Struggle between Immigrant Radicals and the US Government at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century does a great job of exploring the many violent clashes between anarchists and the federal government in the early twentieth century that inspired the rise of the civil-liberties movement.

I can’t help but think of Frederick Douglass as someone who, at the end of his long life, had every reason to be pessimistic for the nation’s future. Step back and consider the dramatic changes he had witnessed. Born into slavery, Douglass eventually freed himself and became one of the leading abolitionists in the North. Douglass pointed to the nation’s hypocrisy in its celebration as a freedom loving nation. He lived long enough to see his two sons fight to end the institution of slavery. In the years that followed, Douglass campaigned for civil rights for women and African Americans, and stood up against a growing nativism in response to an influx of immigrants.

He also lived long enough to see the gradual erosion of Black civil rights in the last years of his life.

Douglass’s defiance was on full display in one of his last major speeches delivered in Washington, D.C. on January 9, 1894.

Though it may strike down the weak to-day, it will strike down the strong to-morrow. Not a breeze comes to us now from the late rebellious States that is not tainted and freighted with negro blood. In its thirst for blood and its rage for vengeance, the mob has blindly, boldly and defiantly supplanted sheriffs, constables and police. It has assumed all the functions of civil authority. It laughs at legal processes, courts and juries, and its redhanded murderers range abroad unchecked and unchallenged by law or by public opinion. Prison walls and iron bars are no protection to the innocent or guilty, if the mob is in pursuit of negroes accused of crime. Jail doors are battered down in the presence of unresisting jailors, and the accused, awaiting trial in the courts of law are dragged out and hanged, shot, stabbed or burned to death as the blind and irresponsible mob may elect. We claim to be a Christian country and a highly civilized nation, yet, I fearlessly affirm that there is nothing in the history of savages to surpass the blood chilling horrors and fiendish excesses perpetrated against the colored people by the so-called enlightened' and Christian people of the South. It is commonly thought that only the lowest and most disgusting birds and beasts, such as buzzards, vultures and hyenas, will gloat over and prey upon dead bodies, but the Southern mob in its rage feeds its vengeance by shooting, stabbing and burning when their victims are dead.

It must have been a difficult speech to write and deliver as Douglass was forced to respond to many of the very same arguments that racist Americans had posed to the idea of Black civil rights throughout the entire nineteenth century.

And yet Douglass somehow managed to end his speech by reminding his audience of the power of the nation’s founding ideals.

But, my friends, I must stop. Time and strength are not equal to the task before me. But could I be heard by this great nation, I would call to mind the sublime and glorious truths with which, at its birth, it saluted a listening world. Its voice then, was as the trump of an archangel, summoning hoary forms of oppression and time honored tyranny, to judgement. Crowned heads heard it and shrieked. Toiling millions heard it and clapped their hands for joy. It announced the advent of a nation, based upon human brotherhood and the self-evident truths of liberty and equality. Its mission was the redemption of the world from the bondage of ages. Apply these sublime and glorious truths to the situation now before you. Put away your race prejudice. Banish the idea that one class must rule over another.

Recognize the fact that the rights of the humblest citizen are as worthy of protection as are those of the highest, and your problem will be solved; and, whatever may be in store for it in the future, whether prosperity, or adversity; whether it shall have foes without, or foes within, whether there shall be peace, or war; based upon the eternal principles of truth, justice and humanity, and with no class having any cause of complaint or grievance, your Republic will stand and flourish forever.

His faith in the nation’s future wasn’t completely extinguished, even as he watched as the door on Black civil rights was quickly closing. We know how long it took for it to begin to open again.

I am certainly not here to tell anyone how they should feel about the United States or how to assess its future. What I would suggest is that our knee-jerk predictions of civil war reveal a tendency to see violence as somehow the exception in American life or the result of an assumption that Americans are inherently a more peaceful people compared to other nations.

Perhaps this is a relic of our long embrace of ‘American Exceptionalism.’

It’s helpful to remember that we didn’t just magically arrive at this moment, that our history is full of highs and lows, sharp turns, and long retreats.

And, yes, much of it is bathed in blood.

Excellent essay. Political violence -- sometimes barbaric -- has been with us almost since the country's founding. Our failure, or inability, to remember it and incorporate it into our understanding of our history is remarkable, so wedded are we to the mythic notion of the U.S. as an always (and positively) exceptional nation. I also recommended thefine Grinspan book which you cite.

Thanks, Kevin - it's a bleak kind of optimism, but I needed to read that passage from Douglass today.