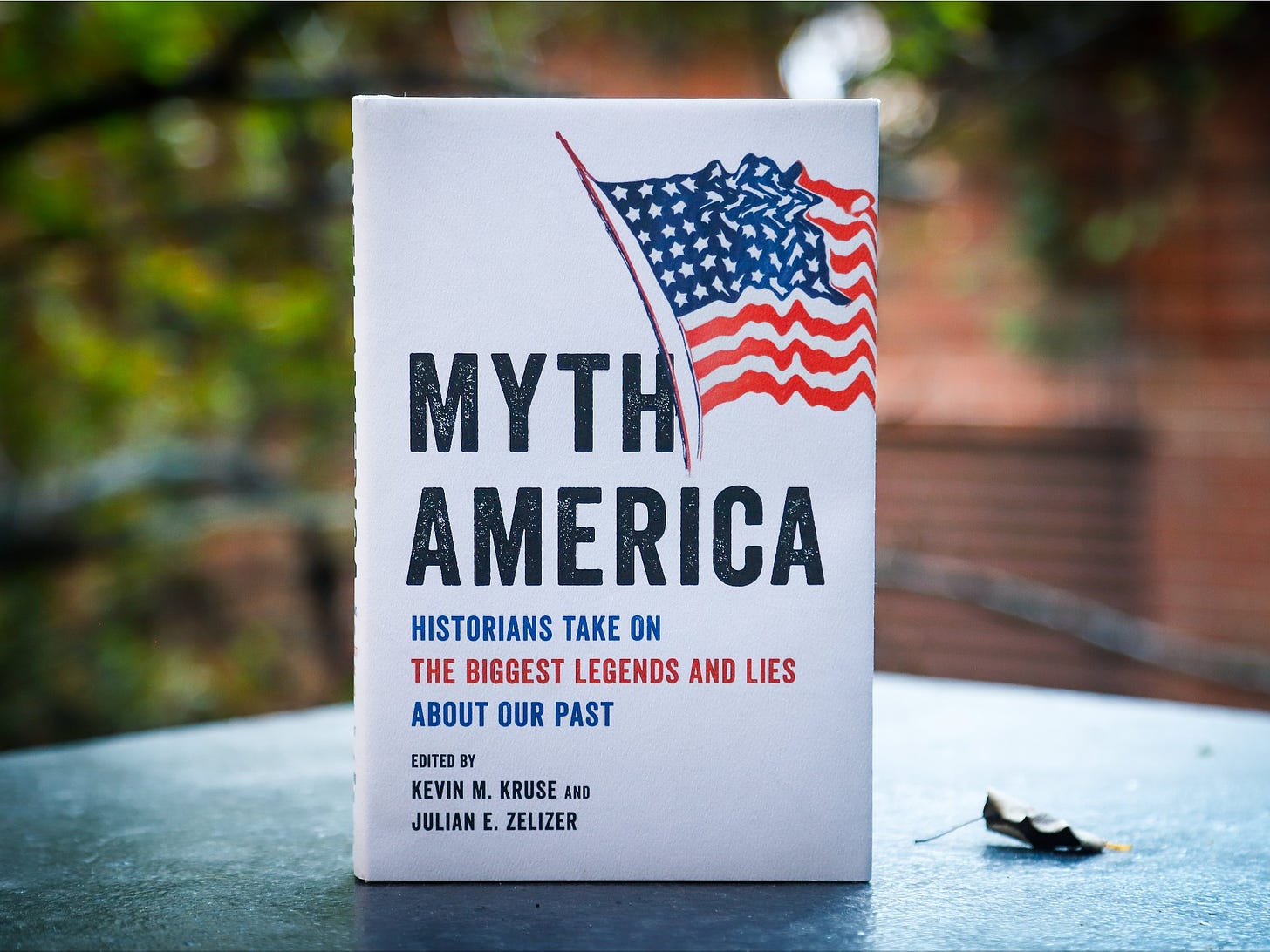

I am currently making my way through Kevin M. Kruse’s and Julian E. Zelizer’s new collection of essays, titled, Myth America: Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past. The book brings together some of the best historians to challenge various distortions and myths about the American past.

Overall, the essays are well written. As someone familiar with the scholarship of many of the authors, I can say that the chapters offer an accessible and helpful introduction to their respective fields of study.

As someone who has long been interested in memory and myth, I was particularly interested in how Kruse and Zelizer frame this project and introduce the essays.

While the introduction is helpful, it left me with a few questions and concerns. The editors acknowledge that there is nothing new about the mythologizing of the American past, but they place a great deal of emphasis on the assault on truth from within “the conservative movement in general and the Trump administration in particular.” We all remember White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s claims of record attendance at Trump’s inauguration in January 2017.

The former president butchered American history more times than I can count and his sycophantic supporters encouraged him every step of the way. It was nauseating.

According to Kruse and Zelizer, “The Trump presidency pushed the country to this crisis point, but it was able to do so only because of two large-scale changes that have in recent years given the right-wing myths a huge platform and an accordingly large impact on American life.” Those two factors include the rise and expansion of conservative media and social media.

There is no question that the Trump years and the ongoing fight to control how certain aspects of American history are taught in public schools has encouraged and reinforced bad history. It is also true that conservative media and the Internet have given life to old and new myths about our past.

However, this emphasis on Trump and the Republican Party doesn’t fully capture the claims of some of the essays in this volume. Karen Cox’s chapter on the Lost Cause is a reminder that myth making about the Civil War era itself has a long and complicated history that, in many ways, transcends the history of both political parties.

As recently as the 1990s, Democrats embraced aspects of the Lost Cause to advance their own political agendas.

Eric Rauchway hesitates to describe the assumption that the New Deal was a failure as a myth in his contribution and admits that it is “not a tale tightly woven in the American story.”

His essay, as well as some of the others, raises the question of how a historical myth is defined and who has the authority to define it as opposed to a difference in interpretation and emphasis.

My larger concern is that readers will finish the introduction and this fine collection of essays with the belief that myth making about the American past exists solely among Republicans and conservatives. By extension, somehow Democrats and liberals exist outside this confusing and chaotic world of social media and misinformation and enjoy some sort of privileged access to historical truth and interpretation.

Is there a book to be written or edited about the ways in which liberals mythologize and distort the American past?

Though I am confident that this was not their intent, the framing appears to pit academic historians against Republicans and their conservative allies. I am not sure this is such a good look for academic historians, especially if the goal is to encourage Americans to think more critically or carefully about the past.

This is where the emphasis should be placed, as the editors themselves briefly acknowledge.

Despite the fact that the term revisionist history is often thrown around by nonhistorians as an insult, in truth all good historical work is at heart “revisionist” in that it uses new finding from the archives or new perspectives from historians to improve, to perfect—and, yes, to revise—our understanding of the past.

This points to the real challenge that historians face in combating untruths and historical myths in today’s political and cultural climate.

Most people simply do not understand how historical scholarship is crafted as well as why and how it is revised over time. It is a problem that is exacerbated by the Internet, where anyone can publish anything about history without any guard rails. The failure to make digital media literacy a priority throughout k-12 education means that most people today have little ability to effectively search for and evaluate information online.

As someone who has worked hard in the classroom, in my published work, and in public presentations to challenge some of the most popular myths about the Civil War and the Confederacy, I have never seen myself as waging a defense of historical truth against Republicans or conservatives generally.

Certainly, the Black Confederate myth (an extension of the “loyal slave” myth), which was first introduced in the 1970s, continues to be propagated by conservative reactionaries, but most of what I’ve encountered over the years are people who are simply misinformed or are incapable of adequately interpreting primary sources that they’ve found online.

They are not pushing a particular political agenda and I think I would have found even less success in my public-facing efforts over the years if I had approached the many Civil War myths and distortions in such a way.

These comments shouldn’t in any way steer anyone away from reading this book. Like I said up top, it’s a fine collection and I applaud Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer for bringing such a talented group of historians together in one book.

Kevin, you’ve done some excellent teaching here, as always. And between you, Dr. Joanne Freeman, and the Washington Post, I’ll now have to buy this book.

As a librarian, I will tell you that people have many reasons for not finishing books they’ve started. And many do not read introductions but go straight to the first chapter, or essay in this case. I’ll be checking my Hernando County, Florida, public library system to see how many copies they purchase, since 45% of registered voters here are Republican and only 26% Democrat (I get lonely down here).

As a loyal Republican wife who quit the GOP when dt came down that brass, not gold, escalator, I can tell you that my many family members who still support dt, including my beloved husband of forty-six years, will not read this book. However, they WIIL hear my opinions which become informed by this book. And I think that is a good goal for any academic historians.

In my rube opinion, you may well believe you never “approached the many Civil War myths and distortions in such a way” but I have seen you both tried and convicted of being just another liberal trying to tear down the South, so what you may or may not intend readers to think has no bearing on what they think.

This is where many err, again IMO. It was political then and it is political now and you cannot change that. The fact that the conservatives fighting for slavery were Democrats then (and for decades after) and those fighting for the myths of confederacy now are mostly Republicans is simply the truth. Not admitting that fact and the political exploitation leaves too much history out.