Last week I was interviewed by my friend Stan Deaton from the Georgia Historical Society. I thoroughly enjoyed our discussion and hope you will have a chance to take a listen. That said, I was disappointed with my response to his final question about my hopes for the upcoming Semisesquicentennial. In fact, I think I totally dropped the ball in my response.

If you don’t know, the United States Semiquincentennial, also called Sestercentennial or Quarter Millennial, will mark the 250th year of the “nation’s birth” in 1776. My less than satisfactory response is, in large part, a reflection of my sense of uncertainty and even doubt that a national commemoration is even possible.

This is unfortunate, because I actually believe that such moments are opportunities to remind ourselves of a shared history and shared values. One could argue that we need this reminder now more than ever.

Congress created the America250 Commission, which promises to “tell the American story through videos and the most inclusive commemoration in our history.” That’s a tall order. A number of organizations here in Boston are hard at work in marking the anniversaries of key events leading up to independence. I suspect that cities and states are at different stages in their planning as well.

We are in the midst of a bitter debate over how to think about and even teach American history, especially the history of slavery and the long history of racism and white supremacy. Numerous polls, however, suggest that a majority of Americans believe that the teaching of these subjects is important, but activists on the extreme left and right always seem to find a way to drown out these voices in their insistence on reducing American history in one way or the other.

If the debate seems more intense, it’s important to remember that it is nothing new. Politics, consumerism, and activism were all present during the nation’s bicentennial. As historian Tammy S. Gordon writes:

Several historical processes—consumerism among them—had aligned by July 4, 1776, to make the idea of the public as a relatively homogeneous unit an antiquated one. First, the civil rights movement had made a profound impact on American culture, and chipped away at the dominant notion of an American cultural consensus. Counter-culturalists and feminists picked up the banner by pointing out that Americans needed less conformity to white, male, middle-class norms and more experimentation in behavior, belief systems, and expressions. Historians, particularly those innovating in the new social history, were part of this change. Second, changes in marketing, specifically the shift in the late 1950s from mass marketing to target marketing, stressed Americans’ differences from one another by creating marketing and products for individual lifestyles. Third, American politics was starting to decentralize, for the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the economic woes of the early 1970s forced Americans to question the expansion of the federal government since the New Deal and look for alternatives. (p. 5)

Perhaps we should be focused more locally in bringing Americans together over the next few years.

That seems to be the lesson that Gordon learned in researching her book:

The results were sometimes unpredictable: while attendance at large-scale events disappointed planners, Americans enthusiastically embraced other activites: local history, folklore, genealogy, television coverage of national commemorative events, and bicentennial-themed shopping. Citizens participated heavily in community events, public art initiatives, community improvement projects, and historical projects in churches, schools, museums, and historic sites. While a centralized nationalistic focus led by the federal goverment nevery fully surfaced, the people embraced other forms of commemoration. A lack of fervent nationalism as expressed in the more centralized celebration of 1876 did not necessarily equate with apathy in 1976. As a whole, Americans engaged diversely and broadly in the commemoration. (p. 9)

We should probably keep this in mind moving forward.

The federal government was probably wise not to form a Civil War sesquiecentennial commission as it did for the centennial in the early 1960s, but that didn’t prevent individual states and a host of other institutions across the country from putting together a highly educational commemoration. The National Park Service and the state of Virginia led the way. Many of these events directly addressed the tough questions surrounding race and slavery, even in places like the former capital of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia.

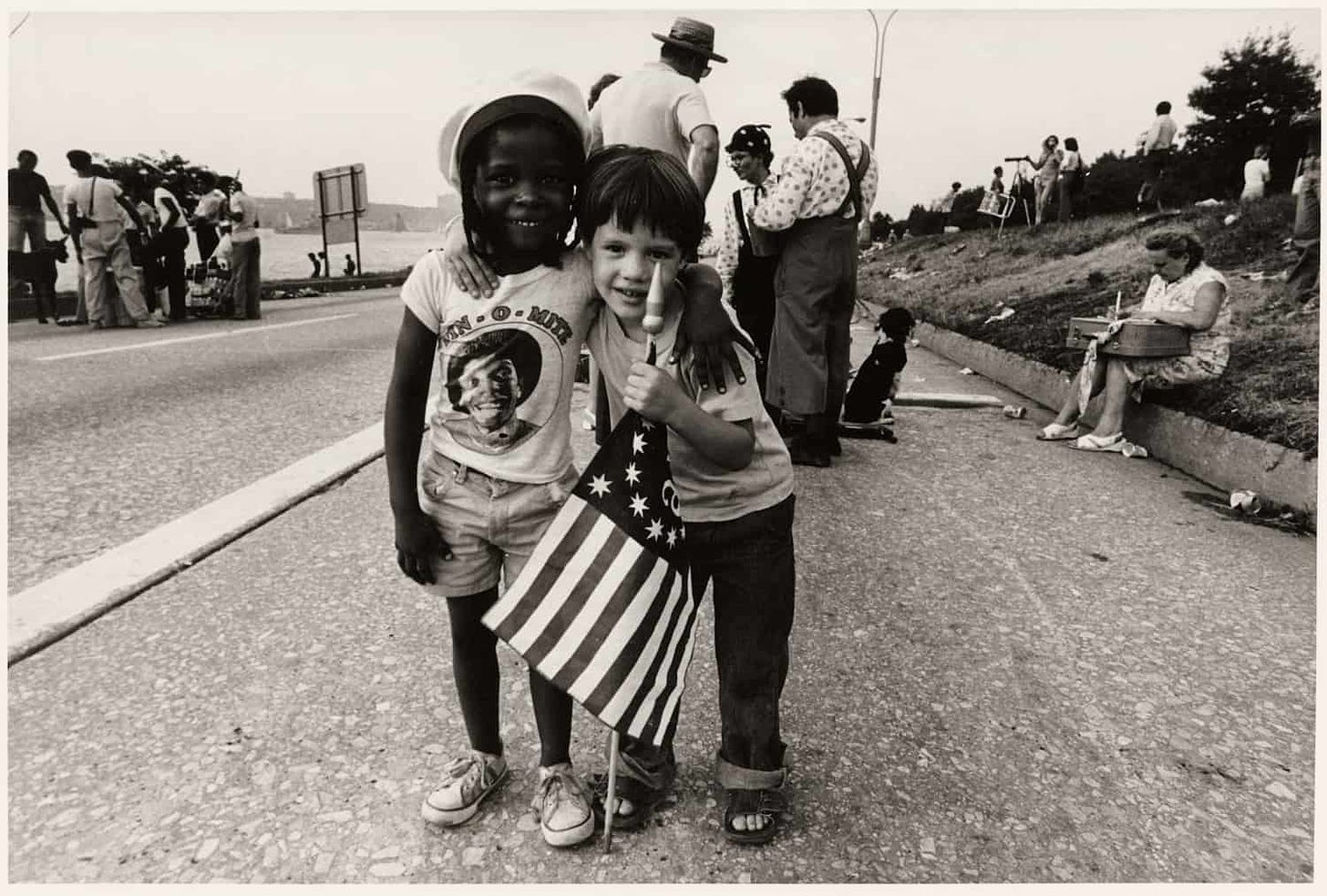

Whether we can achieve the same level of success in connection with the founding of this nation has yet to be determined, but I remain optimistic. There are ways to bring people together from different backgrounds to reflect on important questions that we may disagree about and at the same time acknowledge a shared history and set of values that we all hold dear.

I hope that Americans, who choose to take part in upcoming semisesquicentennial events, are challenged intellectually and are given the opportunity to find meaning in the past that informs their own lives and helps to connect them with the diversity that has always defined this nation.

I hope we can come together as a nation to observe the 250th anniversary of the founding. American

history is going through a rough period that will probably continue for some time to come. It doesn't tell the story that many in the country would like it to tell in the way that many want it told. I think this is true whether one is on the political right, the political left or in the center. But there is a story there that needs to be told and celebrated. The founding vision for this country was radical, for the late 18th century. It scared the bejesus out of the ruling elites in Europe. But it was narrow and exclusive and relied on enslaved people. And, fortunately over the last two and a half centuries we have expanded that vision, not as fast or as completely as we should have but we have expanded it and we are still expanding it. I don't think it will ever be complete. And, I think you make a positive contribution to telling this story

Quoting Ty Seidule, "I want more history". The more (accurate) stories that are included in our national story, the richer and more truthful it will be.