Moving Beyond the Empty Pedestal

How should communities reimagine public spaces where Confederate monuments once stood?

Confederate monuments are no longer coming down, but the hundreds that have been removed have left empty spaces in cities and towns across the country. For many communities, the question of how to utilize these spaces and whether new monuments should be dedicated remains an open question.

Emily Watlington sums up what is at stake in reappropriating these public spaces in the wake of the most recent round of removals following the police murder of George Floyd in 2020:

Ever since, I have eagerly awaited what might take their place. How, I wondered, might we represent American history anew, grappling honestly with slavery and genocide? Would a new wave of sculptures lean toward figuration? Would they be abstract? Would they be temporary or permanent? Would they honor brave survivors and heroes, or mourn tragic losses?

It’s been almost five years now, and the question has changed: it’s no longer how the monuments will look, but whether there will be very many at all. Committee after committee has been formed and disbanded, while the plinths and on Richmond’s Monument Avenue remain empty. Committees are unable to reach consensus not only in the South.

The question of how to move forward is a political hot potato that many communities are simply not ready to address. Watlington offers a number of examples of recent commemorative efforst in places like Montgomery, Alabama through EJI’s memorial to the victims of lynchings and the University of Virginia’s new memorial honoring enslaved workers, who helped to bring Jefferson’s vision to fruition, but these are additions to the memorial landscape rather than replacements.

Cities like Richmond, Virginia—the former capital of the Confederacy— and numerous other communities still need to decide what, if anything, will be added to the sites, where Confederate monuments once stood.

Whatever else goes into these public discussions, I highly recommend that commissions charged with this important project utilize their student populations.

Unfortunately, student voices have been largely absent from public discussions concerning these issues. This is a curious omission given that these discussions have been framed largely around the question of how communities should move forward from these relics of Confederate memory. Sadly, the very people who will have to live with these decisions have been ignored or not engaged directly.

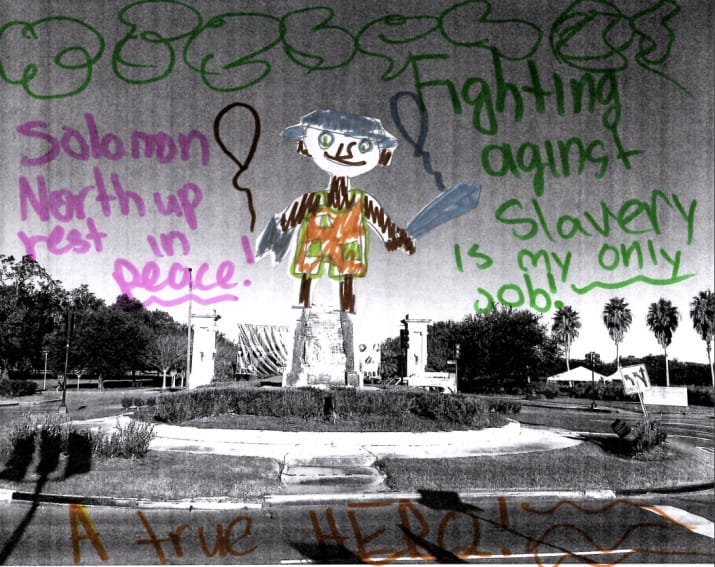

The one notable exception to this is New Orleans, which removed four monuments in 2017. Shortly thereafter, students, mainly third graders, were offered to reimagine these public spaces with new monuments. Aided by 826 New Orleans, which supports efforts to improve students’ reading and thinking skills, the results speak for themselves.

Students thought carefully and broadly about ways to commemorate their city’s history and culture. While a monument to Solomon Northup and Ruby Bridges makes perfect sense for historical reasons, students also singled out regional foods such as crawfish and beignets as worthy of commemoration.

The result of their efforts was a book that featured student artwork and thoughts about how to move forward with new monuments and other commemorative forms.

One of the reasons why I value student input is that compared to previous generations they are now learning a much richer and more inclusive history of the United States. Changes to the curriculum are a reminder that history education is itself a process of remembering and forgetting. Rather than view the removal of monuments as tantamount to erasing the past, students can show us the way forward by highlighting individuals and events that have been overlooked, deserve to be recognized and that have the potential to unite the community.

There is likely even more opportunity in soliciting the input from middle and high school students. I suggested one approach back in 2017.

City and town commissions should send out invitations to every public and private school throughout the community. Each school will send representatives from grades ranging from the 5th through 12th grades. These students will take part in a day-long discussion around the the question of how their community should commemorate the past at sites that have witnessed the removal of monuments. They will need to be provided with plenty of direction, historical background and other relevant information as a foundation for these discussions.

Small working groups should be formed that each reflect the racial, ethnic, and economic diversity of their respective communities. These small groups will encourage students to listen to one another and engage with their peers from very different backgrounds and perspectives about the present and past. Their conversations will ultimately culminate in suggestions, arrived at by consensus within each group, about how to move forward.

Watlington emphasizes the work of Bryan Stevenson and James McAnally, who have helped to transform their respective communities through the development of new commemorative spaces. Their results are impressive and break new ground in public commemoration of the past, but most places will need to find inspiration elsewhere.

Soliciting advice from local students is a grassroots approach that has the potential to impose legitimacy on an otherwise divisive and politically fraught process. No doubt, the anticipation of such challenges has prevented some communities from engaging in this important work, but perhaps our children can show us the way forward.

This was an excellent piece by Ms. Watlington, and pulled together a lot of useful threads on the need for imagination in public commemoration. One interesting sidelight is that her comment about re-recting monuments on the "plinths" or bases of one-time Confederate-themed monuments is now purely metaphorical as far as Richmond is concerned. The bases of the Lee, Jackson, Stuart, Maury and Confederate Soldier and Sailors monuments are gone in their entirety. Anything new in those places (other than the Jackson monument, which is now roadway) will be literally from the ground up.

“They will need to be provided with plenty of direction, historical background and other relevant information as a foundation for these discussions.”

Great idea. I’d like to see this done with the lightest touch possible so the kids can be as free as we can make it from heavy-handed indoctrination.