Moses Didn't Serve the Confederacy. He Survived It

Remembering one of the thousands of enslaved men who took part in the battle of Gettysburg on this 160th anniversary.

This weekend thousands of visitors will visit the Gettysburg battlefield on this 160th anniversary. They will walk “Pickett’s Charge,” peer over the rocks in the Devil’s Den, and read the inscriptions on a monument or two.

Very few, if any, visitors will have the opportunity to consider the experiences of the thousands of enslaved men who were forced to accompany Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia into the free state of Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863. This is unfortunate because understanding the experiences of these men and the fact that they were on the battlefield during the three days of fighting can help us to truly appreciate the significance of the battle in American history.

Today I want to focus on one particular man by the name of Moses, who was enslaved by Col. Clement A. Evans of the Thirty-First Georgia Regiment.

He wrote the following in a diary entry in January 1864:

The day’s history would be incomplete without the mention of the advent of Moses to his accustomed place of cook, hostler & servitor-general. He has just returned after a month’s absence from the army at home entering upon his duties here at once. Moses, an old family servant, is utterly spoiled. He regards himself as my guardian, thinking doubtless that but for him I would have been lost long ago. I appreciate his fidelity and shall reward his services by affording him after the war a serene old age.

Black as the ace of spades in color, and my bondsman and slave for life, yet he is happier than Greeley, Beecher, or Lincoln. It would be cruelty to give him his freedom and in fighting to retain my right of property over him, his children and fellow bondsmen. I contend but for their happiness. He went with me through the Pennsylvania Campaign last year, being well apprised that he had but to remain in order to be free. I offered him there the choice of remaining or returning and he scouted the idea of living among Yankees. While Moses thinks his is not so good as a Southern white man, yet he feels immeasurable superiority over the Yankee whites.

He rode his horse with serene dignity through the streets of Gettysburg and York dressed in full Yankee blue often giving to the gaping Pennsylvanians a stiff military salute. Once he stopped at a house by the wayside to get some butter and was overpowered by the attentions of some Dutch damsels of the place. He came away offended at the familiarity they had presumed to treat him with. I cannot boast much of his courage. Bursting shells demoralize him, and the singing Minie ball quickens the first law of his nature to wit, self-preservation. But I will say for him that he fears no danger if he is told I am wounded.

Once he came to me on the false rumor of my being wounded, and at Gettysburg he came also to the very line where I was. He manifests great apprehensions for my safety. Said he once: ‘They have shot you twice & shot all about you many times; some of these times if you don’t care, they will shoot you bad, & then what will become of me.

I have been this minute in speaking of Moses, because he came into the service with me, and prefers enduring these campaigns rather than the more comfortable labor at home. Possibly his name may occasionally occur in these pages to be hereafter written. But, should it not, let him ever be remembered for his fidelity.

While we know plenty about Evans, we learn very little about Moses from this entry. Like most of the body servants or camp slaves attached to Confederate armies during the war, we must rely almost exclusively on the written accounts of their owners.

Having read hundreds of such accounts there is little in Evans’s diary that is unique in his characterization of Moses. He was faithful to the end, thought little of his own safety, and risked his life for his master on more than one occasion. I have no doubt that Evans was sincere in what he wrote, but it tells us very little about how Moses viewed slavery and the time in the army as a body servant.

But if we listen closely we can glean a little bit about Moses’s war. We know that Moses traveled a great deal between camp and home and clearly knew how to handle a horse.

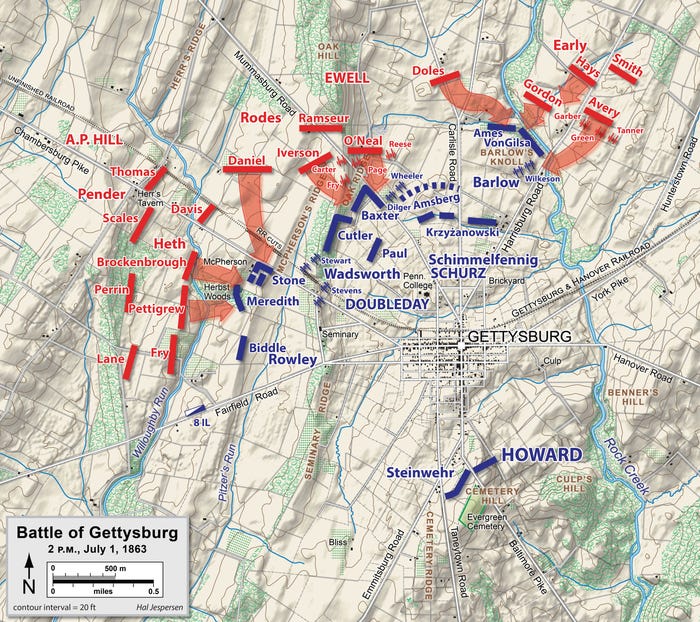

During the Gettysburg Campaign the Thirty-First Georgia was attached to John B. Gordon’s Brigade, Jubal Early’s Division of the Second Corps and was one of the first units to enter Pennsylvania in late June 1863.

He likely wore parts of a uniform picked up from a captured or dead United States soldier. This was not uncommon and may have made it easier for Moses to see himself as a military man and may also help to explain Evan’s description of a self-assured Moses on his horse riding through Gettysburg and York.

It is difficult to explain Moses’s supposed “fidelity” toward Evans during the campaign. As one of the first regiments to enter Pennsylvania, Evans likely would have heard about or even witnessed the rounding up of hundreds of free Black men, women, and children to be sent back into the Confederacy as slaves.

What calculations, if any, did he make about what would best guarantee his safety, we can only speculate.

Moses traveled as far as Wrightsville, PA before returning with the rest of Early’s division to link up with Lee’s army near Gettysburg by July 1. During the previous year the regiment had seen action at Gaines’ Mill, Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Second Winchester. Moses was no stranger to the battlefield.

Moses may have assisted Evans at some point during the regiment’s assault against the Union XI Corps at Barlow’s Knoll on the first day of fighting.

Perhaps Moses knelt alongside his owner looking out at East Cemetery Hill later that evening in anticipation of an attack that never came and that has fueled speculation ever since.

We can also do little more than speculate as to why Moses risked his life at Gettysburg and elsewhere and why he remained with Evans. We should resist Evan’s self-serving explanation of unquestioned loyalty. As one of the last regiments to recross the Potomac following the failed Confederate assaults on July 3, Moses may have witnessed enslaved men fleeing toward Union lines or elsewhere.

We know that Moses did not join them. It is likely that Moses had family and friends back in Georgia that he yearened to return to at some point. Perhaps he decided that the dangers of freedom were more risky than his current situation.

Understanding the roles that the thousands of body servants and impressed slaves assumed in the Army of Northern Virginia is essential to fully understanding how an army of roughly 75,000 was able to move, survive, and carry out its orders.

But remembering Moses can also help us to better appreciate Gettysburg’s overall significance. This is something that visitors should keep in mind the next time they are standing at the Virginia monument and trying to imagine a successful Confederate assault on July 3 or debating what might have happend had “Stonewall” Jackson carried out a night time assault against Union positions on Cemetery Hill.

These what-ifs stir the imagination, but ignore their consequences for real people.

The lives of thousands of enslaved people hung in the balanace at Gettysburg and for the remainder of the life of the Army of Northern Virginia. A Confederate victory at Gettysburg and an independent Confederacy would have meant the continued enslavement of Moses, his family, and millions of enslaved people.

Something to remember for the next time you visit Gettysburg or any Civil War battlefield.

At 10:30 on July 3rd, I will be leading a tour about enslaved men in in the Army of Northern Virginia. This walk is sponsored by CWI and the NPS. We will be meeting at the Lee monument. Your call to remember the enslaved has been answered!

I am pleased to see that Moses is getting attention on your blog after I shared the Evans diary entry with you. Reading against the grain when examining the Evans diary offers a unique opportunity to explore how a slave navigated life in the ranks. And to think that the NPS is sponsoring a tour on enslaved men on the anniversary of Picketts charge speaks to sweeping interpretive shifts at NPS sites . And to know that people of all perspectives can be part of the conversation tomorrow, that no one is going to be banned from attending the walk , and that free speech will be respected fulfills the promise of public history. I am very excited about tomorrow ‘s program as it builds upon our good work with Jill Titus at CWI last June. Pete

"Perhaps he decided that the dangers of freedom were more risky than his current situation."

The "devil-you-know."

It's an individual calculation, and easily understandable in those terms, even if we know next to nothing about Moses' own perspective. Making that choice certainly doesn't tell us a great deal about what Moses actually wanted, or his supposed commitment to either Clement Evans or the Confederacy.