Monuments and Memory at Gettysburg: Another Way to Interpret the Pickett-Pettigrew Assault

[Pulled this post from the archive on this 160th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg and “Pickett’s Charge.” (Originally published on April 21, 2017)]

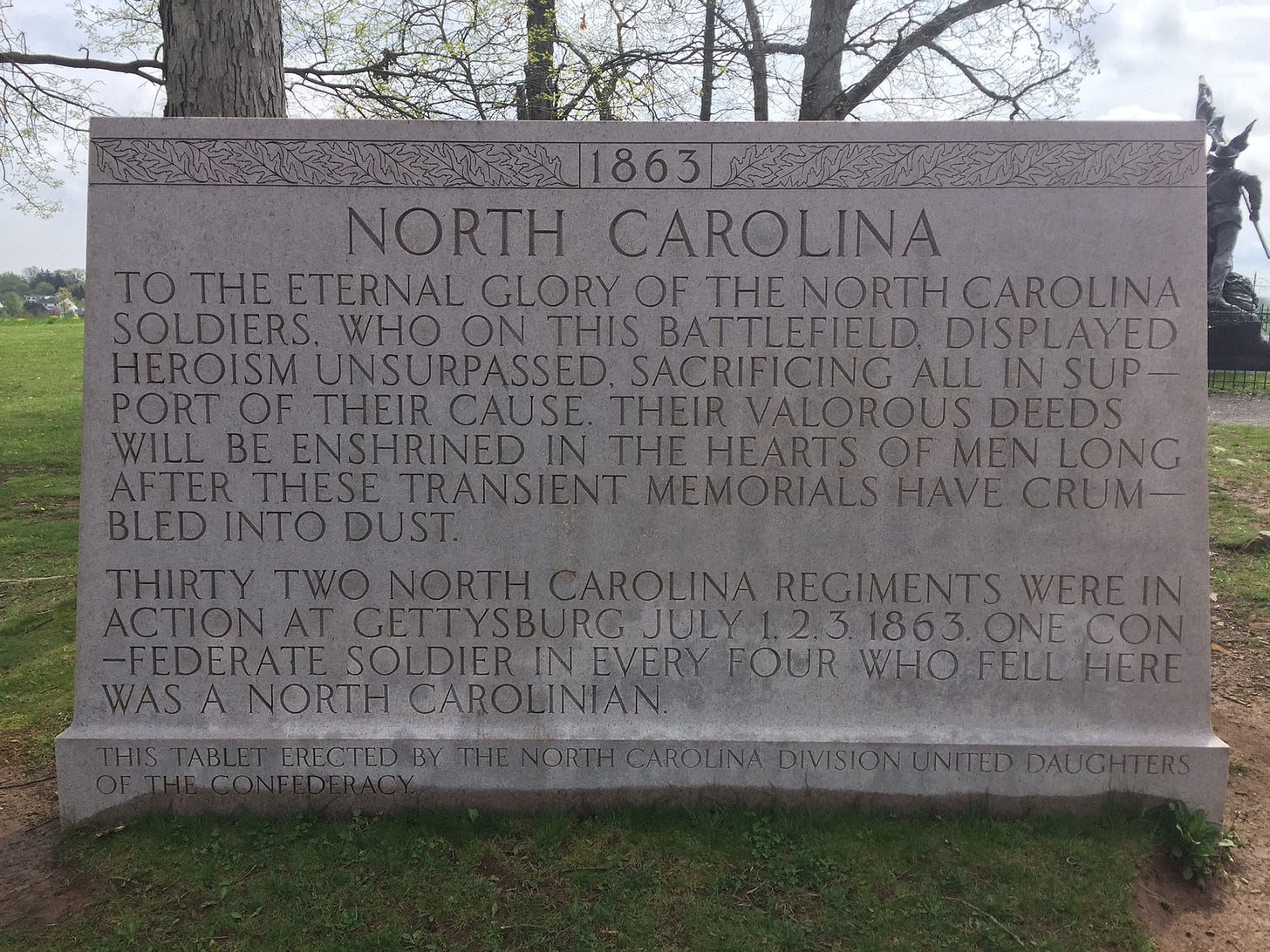

This morning I spent some time reflecting at the North Carolina monument along Confederate Avenue at the Gettysburg National Military Park. I was thinking specifically about the entry points for engaging students on the battlefield. After a few minutes a group of high school students gathered around the monument with a guide.

He said nothing about the monument and for close to 20 minutes recounted in great detail the fighting that took place on July 3, 1863. At most half the group was paying attention and as the talk continued more and more tuned out. At the end the guide asked if there were any questions and the group walked back to their bus.

Now don't get me wrong, students and visitors alike need to understand what happened on the battlefield, including how the decisions made by commanders shaped the outcome of the battle and the experiences of the soldiers themselves.

The Gettysburg battlefield offers some wonderful opportunities to talk about the ebb and flow of battle, but I would suggest that students do not need a great deal of detail. In fact, I suspect that students lose most of this knowledge within a few hours of departing the field.

Before proceeding let me suggest that the most important decision that a teacher needs to make before bringing students to a place like Gettysburg is what they want their students to learn. This may seem obvious, but I've seen too many teachers hand over that responsibility to others.

If possible, contact your guide beforehand to help frame their time on the battlefield. What kinds of questions do you want students to consider? How will this trip reinforce what has been and/or will be discussed in the classroom? If you want students to think about the big questions surrounding American freedom, don't rely solely on Morgan Freeman in the visitor center's introductory movie. There are plenty of ways to bring these questions onto the battlefield itself.

OK, back to the North Carolina monument. In this case the guide missed a wonderful opportunity to connect the North Carolina monument with how we remember and memorialize soldiers and the impact of the battle on the very people who owned the land on which the fighting occurred.

Here is how I have approached it in my own teaching.

First, I would orient students to this specific spot on the battlefield and provide a basic overview of what happened on July 3, including the participation of North Carolinians in the Pickett-Pettigrew assault. Then I would have students read and reflect on the tablet accompanying the monument. What are the keywords or phrases that stand out? What are visitors expected to believe about these soldiers? What exactly is the “cause” that is referenced here?

Now move to the monument itself, which in my mind is one of the most impressive on the entire battlefield. You may want to mention that its sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, carved Mount Rushmore and was also a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Have students reflect on how the monument reinforces the meaning of the tablet just discussed. What features of the monument stand out and what emotions do you believe the sculptor hope to invoke?

The entire monument highlights the desperate and dangerous forward momentum of the rank and file. These men are committed to sacrificing everything to achieve victory. At some point ask students to suggest what the kneeling soldier is pointing at. After considering a few suggestions point the group to the Bryan Farm along Cemetery Ridge.

Abraham Bryan, a free black man, purchased this farm in 1857. During the last week of June, Bryan, along with much of the rest of the black population in and around Gettysburg, fled as Lee's army entered Pennsylvania. As soon as the Army of Northern Virginia entered the state they were ordered to capture as many fugitive slaves as possible and send them back south. These advance units made little distinction between former slaves and free blacks.

Throughout this campaign Lee's army functioned as slave catchers. The presence of the Confederate army threatened the very freedom of this community, who chose to build their lives just a few miles north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

On July 3, 1863, Confederates were now poised to attack across the property owned by this free black man.

Like other residents of the town, Bryan returned to a devastated home and farm. He eventually filed a claim with the federal government, but only a small portion of the damage was covered. Bryan sold his property in 1869. [For more on Bryan and the African-American experience, read Margaret Creighton's Colors of Courage: Gettysburg's Forgotten History: Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War's Defining Battle]

Now return to the North Carolina monument and tablet with your students. How, if at all, does the story of the Bryan family alter the meaning of this monument? How might Abraham Bryan and the rest of the black community have responded to such a declaration during the dedication ceremony in 1929 within site of their former home? Can these two sites be reconciled?

You will rarely see visitors stop for a significant amount of time at the Bryan farm, but I would suggest that it is just as important as any other site on the battlefield. Including the Bryan family should not be understood simply as broadening the historical narrative. It is, unfortunately, still a matter of uncovering a lost past.

I am very interested in placing specific sites in relationship and even in tension with one another as a way to understand not just the Gettysburg battle, but its broader significance in American history. There was something at stake in this battle for the entire country and you can begin to understand it on the field itself.

I would suggest that guides do not write lesson plans, which would certainly have altered this presentation. You have written a great lesson plan here. You even make me miss teaching 8th graders - I would have loved to have taught my Texas kids this one, virtually of course.

Regarding the painting you shared. The area where the rebels are standing looks so flat. Until I stood at the Virginia monument and looked east toward the Meade monument, I’d not realized how literally uphill the Pickett-Pettigrew assault was. I understand the Federal soldiers were chanting “Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!” The rebels only charged once and gave it up as a bad job. I wonder how the percentage of KIA and wounded compare in those two actions.