On Tuesday I had the honor and pleasure of taking part in what is likely the first ever battlefield tour at Gettysburg National Military Park focused entirely on the experiences of African Americans, including the thousands of enslaved Black laborers who toiled in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia throughout the campaign.

I joined my dear friends and colleagues Peter Carmichael and Jill Ogline Titus for a 4-hour tour that explored some of the most complex and difficult questions surrounding the campaign specifically and the Civil War more broadly. Our goal was not only to show that you can tell these stories on the battlefield, but that they are absolutely essential to understanding what took place and how the campaign unfolded.

In other words, these stores are not simply part of some curious side show that can be easily ignored.

Though we had carefully planned the tour in advance, none of us had any sense of how it would unfold or the reception of the audience.

One of the challenges of leading a tour like this is that there are very few site-specific locations to utilize. You have to be creative and use your imagination to try to tie these stories to the landscape.

Our first stop took us to Oak Ridge overlooking the roads approaching Gettysburg from the west to discuss what the approach of the Army of Northern Virginia meant to the African American community in the town as well as their kidnapping by Confederates in other parts of south central Pennsylvania.

I took the opportunity to help the group visualize the thousands of enslaved men in Lee’s army that functioned as body servants or camp slaves and laborers in various military departments. These men were not serving the Confederacy. They were attempting to survive it.

I also wanted participants to understand from the outset that every Confederate soldier and officer—regardless of whether he owned slaves—understood that their ability to carry out this campaign was dependent on slavery.

We used the Hankey Farm (private property) where Jill did a brillliant job of sharing individual stories of how local Blacks experienced the battle and their interactions with Confederates.

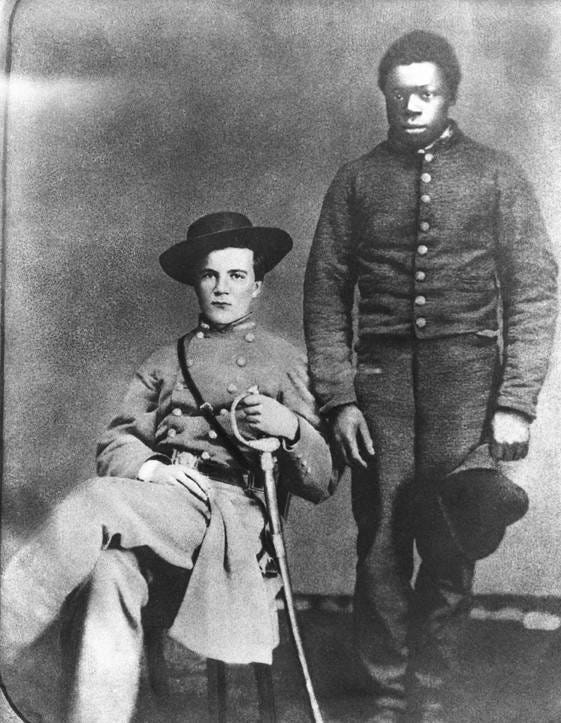

Along Willoughby Run Peter discussed the story of Henry King Burgwyn, Jr. and his body servant or camp slave Kincien. I used photographs of master and slave to flesh out their understanding of honor, manhood, and mastery as well as their assumption that the presence of enslaved in the army constituted one of its great strengths or to use the words of Alexander Stephens, the army’s “cornerstone.”

At the edge of Spangler Woods on the field of “Pickett’s Charge” we shared the stories of the relationship between Edward Porter Alexander and his slave Charley as well as Clement Evans and his slave Moses.

I am embarrassed to admit that I was unfamiliar with Evans’s account before this tour. It beautifully captures how he viewed his enslaved servant and Evans’s inability to see this man as fully human.

Evans wrote the following in a diary entry from January 1864:

The day’s history would be incomplete without the mention of the advent of Moses to his accustomed place of cook, hostler & servitor-general. He has just returned after a month’s absence from the army at home entering upon his duties here at once. Moses, an old family servant, is utterly spoiled. He regards himself as my guardian, thinking doubtless that but for him I would have been lost long ago. I appreciate his fidelity and shall reward his services by affording him after the war a serene old age.

Black as the ace of spades in color, and my bondsman and slave for life, yet he is happier than Greeley, Beecher, or Lincoln. It would be cruelty to give him his freedom and in fighting to retain my right of property over him, his children and fellow bondsmen. I contend but for their happiness. He went with me through the Pennsylvania Campaign last year, being well apprised that he had but to remain in order to be free. I offered him there the choice of remaining or returning and he scouted the idea of living among Yankees. While Moses thinks his is not so good as a Southern white man, yet he feels immeasurable superiority over the Yankee whites.

He rode his horse with serene dignity through the streets of Gettysburg and York dressed in full Yankee blue often giving to the gaping Pennsylvanians a stiff military salute. Once he stopped at a house by the wayside to get some butter and was overpowered by the attentions of some Dutch damsels of the place. He came away offended at the familiarity they had presumed to threat him with. I cannot boast much of his courage. Bursting shells demoralize him, and the singing Minie ball quickens the first law of his nature to wit, self-preservation. But I will say for him that he fears no danger if he is told I am wounded.

Once he came to me on the false rumor of my being wounded, and at Gettysburg he came also to the very line where I was. He manifests great apprehensions for my safety. Said he once: ‘They have shot you twice & shot all about you many times; some of these times if you don’t care, they will shoot you bad, & then what will become of me.

I have been this minute in speaking of Moses, because he came into the service with me, and prefers enduring these campaigns rather than the more comfortable labor at home. Possibly his name may occassionally occur in these pages to be hereafter written. But, should it not, let him ever be remembered for his fidelity.

I will leave it to you to interpret this incredibly rich source. For now, I will point out that this is a wonderful reminder of the warime origins of the Lost Cause.

Finally, we spent some time at the Virginia Memorial to talk about the presence of former camp servants at the monument’s dedication and the broader place of these men in Confederate commemorations throughout the postwar period.

The response from the participants was overwhelmingly positive. People approached me right up until the end of the conference to share their appreciation or to continue the discussion. Their questions and willingness to engage in discussion went far to making this such an enjoyable and educational experience.

From the outset, I had conceived of my book Searching for Black Confederates as a way to think about and even tour battlefield sites like Gettysburg. What a thrill to see it play out in practice.

Thanks to Peter and Jill for helping to make it possible. I hope we have the opportunity to do this tour again in the future.

Kevin,

You were superb on Tuesday as was Jill. To see so many people interested in the stories of enslaved men (we had a full bus, and I bet we could have filled two) reaffirmed my strong belief that Civil War enthusiasts want to hear a wide range of stories. I was also struck by the level of their engagement, impressed by their questions, and pleased that they gave us (me) a little push back. And to populate the battlefield with enslaved people felt like we were reclaiming the landscape for historical actors who had been silenced.

We go back a long way, and if someone had told us in the early 1990s that the day would come when we would lead a tour about slavery on the Gettysburg battlefield, we would have said keep dreaming. What we did with Jill is a powerful reminder of how far the field has come. And let's not forget our NPS colleagues who have been working hard on this front (John Hennessy at Fredericksburg for example, Emanuel Dabney at Petersburg, Keith Snyder at Antietam, and the list goes on).

And finally, I really appreciated your framing the Confederate slave experience as not fighting in the field, but trying to survive in Southern armies. I hope my colleague Scott Hancock succeeds in getting a monument to enslaved people at Gettysburg--and one that reminds all visitors that black men--both slave and free- had a strong presence during the battle.

Interpreting enslaved Confederates with you and Jill was really special, and the experience will undoubtedly rank as one of the high points in my teaching career. And I even got you to go out to the Garry Owen for a drink. But your admission that you once loved the Grateful Dead was disturbing. Any band that promotes the wearing of tie dye shirts is suspect. Listen to the Hold Steady. In time you will come to worship them. (worship might be a little strong)

Pete

I am going to squeeze in a third opinion here. In my life, nothing has ever been "black and white"!

I cannot find an analogy to this phenomenon, something that has been hiding in clear sight, well, since 1619. The history of my family, my clan, as Japanese for in my case three (now five) generations, in the span SINCE this civil war has been incredible and very contrasting. My ancestors came over into slave-comparable occupations (e.g., cane plantation labor) and my relatives practice a broad spread of occupations. My wife's last career was as a longtime staffer of the twice-elected Speaker of the House. Three uncles and my father-in-law served in, and received the Congressional Gold Medal for serving in the WW2 100/442/MIS units.

Myself, I was born in Georgetown, Washington, DC, in 1948.

My parents met and married and otherwise lived in a total of five of FDR's WW2 concentration camps. I am now 75 and have spent my life - since 1963 - trying to discover first the fact, then the shades of that meaning. My parents' generation had to argue for the right to fight in WW2, then the lucky ones merely died fighting in the 100/442/MIS. After one uncle passed on in 1985, my aunt told me he suffered from screaming PTSD all his life.

Japanese Americans maybe were the luckiest non-Anglo-Saxon race. We only started arriving in 1868, not 1619; nor were we standing on the shores in October 1492 to greet Chris.

My mother reacted to the war with rage. She grew up on a poor farm the eldest daughter. Japanese sexism so oppressed her that it seemed racism didn't seriously oppress her until her frightened parents burned everything precious after Pearl Harbor. When they were forced to self-deport to the first of the concentration camps, her mother's health broke. She died of hypertension in the second concentration camp; my mom vented the blame on FDR and 30 years later she still cursed him: the Great White Father.

As a post-WW2 child, my parents always brought me up to be paranoid, to be polite to Caucasians. Frankly, the racism and pressure were unbearable. My father was a Christian convert. I'm still angry.

To summarize and place this in context: I cannot believe how African Americans, virtually every single one of them, could live centuries playing Stepin' Fetchit'. Certainly, employees learn this behavior for a period of the day. A lot of learned behavior is chalked up to "manners". In reading my mother's clan history, a bad attitude was a deep character trait, but RHIP.

I cannot fathom how enslaved men and women and their offspring managed to live dual lives, perhaps multiple lives, entirely to eke out daily existences. Perhaps history will never tease this out.

I believe it is essential for everyone to make the effort. At least, everyone of good will. I am sure there will be a lot of supposition and conjecture without basis, but that's humanity.

I went on a pilgrimage to the Arkansas site of my parents' last two concentration camps last month. While there, I met with (I'm overstating this a tad) George Takei and we started a mitzvah for Rosalie Gould, the onetime mayor of the town of McGeehee, where Rohwer had a tiny cemetery. (George was a child-inmate at Jerome, the other camp, and now there is a talking monument featuring his voice.) Forty years ago, she had the town start to refurbish the site including the two concrete monuments to the servicemen and the inmates themselves. It's now a national monument on the civil rights trail. Where people were kind. we must repay it!

Again, it was traumatic for my parents, for my race, but I cannot start to compare it -- especially as we campaigned for and received a presidential apology and $20 grand each in reparations. At least, the survivors received them.

I will avidly read Kevin's book while I appreciate how lucky some of us ended up.