I’ve been steadily plugging away at my biography of Robert Gould Shaw. I’ve been thinking quite a bit about the controversy surrounding the burning of Darien, Georgia on June 11, 1863.

It’s a key moment for Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts. The regiment had only arrived in the region roughly a week earlier and both Shaw and his men likely had questions about how exactly they would be utilized. For Shaw specifically, this first experience serving under the command of Montgomery stood in sharp contrast to his experiences in the Second Massachusetts Regiment and the campaigns and battles in Virginia and Maryland in which he participated.

Once again, I am surprised by the amount of mental space that the movie GLORY still occupies in my head after all these years. It’s simply impossible to escape when writing about Shaw and the 54th.

The movie’s depiction of the burning of Darien is a great example of this. Though the movie overall does a pretty good job of depicting what took place, it is also highly misleading in certain regards.

First, it depicts Montgomery as the villain, who commands a regiment of undisciplined former slaves who do little more than engage in wanton destruction and depredation. On the other hand, Shaw is depicted as the innocent victim, who apparently had no understanding of what he was getting himself and his regiment into when he enthusiastically agreed to accompany Montgomery on this expedition.

This is seriously misleading and not supported in any way by the historical record.

Shaw and the 54th arrived in Beaufort, South Carolina on the early morning of June 4, 1863. That first day Shaw was greeted by Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who commanded the First South Carolina (Colored) Infantry.

Shaw was familiar with the Unitarian minister, abolitionist, and politician. His commitment to ending slavery could be seen in his membership in the Boston Vigilance Committee, which aided fugitive slaves to his efforts to ensuring Kansas became a free state through his work with the New England Emigration Society to his membership in the Secret Six, which provided financial support to the abolitionist John Brown.

Higginson would have been able to answer many of Shaw’s questions about the military situation in and around Beaufort as well as the work that he and his regiment would be required to undertake.

The two discussed the fighting capabilities of Black soldiers. Decades after the war, Higginson recalled that Shaw had suggested, “that while I had shown that negro troops were effective in bushfighting, it had yet to be determined how they would fight in line of battle.” Though Higginson pushed back on his skepticism, Shaw concluded that, “it would always be possible to put another line of soldiers behind a black regiment, so as to present equal danger in either direction.”

Higginson may have been surprised by the suggestion that bayonets might be necessary to motivate the men of the 54th Massachusetts to face the enemy, but he also recognized that Shaw had only been in command of his regiment for a few months.

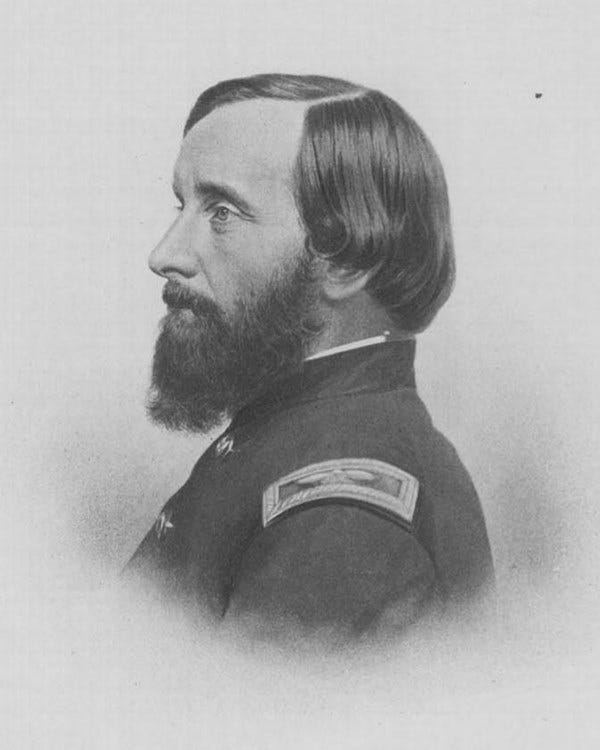

Shaw also briefly met his immediate commander. Colonel James Montgomery’s reputation as a fervent abolitionist was solidified in the Kansas territory during the struggle to determine whether it would enter the Union as a slave or free state. In 1857 he organized free-state men into a “Self-Protective Company,” which he used to intimidate and force out pro-slavery men from the territory. Montgomery fought alongside John Brown on occasion and even helped to plan a foray into Virginia to rescue him after his arrest following the failed Harpers Ferry Raid.

Once the war commenced, Montgomery received a commission as colonel of the 3rd Kansas Infantry. Unlike most people in the army, Montgomery called for the recruitment of African American soldiers at the very beginning of the war. After reporting to the Department of the South in January 1863, he was authorized by General Rufus Saxton to raise a second regiment of Black soldiers from among the population of freedmen.

Higginson likely briefed Shaw on Montgomery’s activity over the previous months. In February, Montgomery led the Second South Carolina Volunteer Infantry twenty-five miles up the St. Mary’s River on the Florida-Georgia border to secure building materials and other confiscated items.

A few weeks later they returned as part of a larger raid to announce the Emancipation Proclamation and recruit as many freedmen as possible for service in the regiment. On March 25, the regiment took part in an even longer expedition traveling up the St. Mary’s River as far as Palatka, Florida and “returning laden with wagons, mules, cotton, forage, freed slaves, and fifteen prisoners.”

Along the way, Montgomery formed a close partnership with the famed Underground Railroad conductor, Harriet Tubman, who arrived in May 1862. Montgomery may have met Tubman in 1860, but the two would have easily bonded over their shared friendship with John Brown and their commitment to ending slavery. Tubman provided important military intelligence picked up from escaped slaves and other informants.

Montgomery led his regiment on its most daring raid up the Combahee River, just west of Charleston just prior to the arrival of Shaw and the 54th. Enslavers remained in the area under the belief that they were safe from encroaching Union forces. Montogmery’s objective was to liberate as many enslaved people as possible—hopefully resulting in additional recruits to his regiment, which still numbered only a few hundred—as well as clear away torpedoes [mines] that hampered the movement of Union gunboats.

Tubman, who accompanied Montgomery on this expedition, provided much needed intelligence about the location of the torpedoes and the disposition of the enslaved on the surrounding plantations, even as she once again placed her own life in jeopardy in the event of capture.

Confederate resistance was minimal, which allowed the expedition to cast a wide net in rounding up the Black population. Montgomery’s men also burned hundreds of acres of crops, rice mills, cotton warehouses, storehouses, and in some cases the mansion homes as well, all with the approval of General David Hunter. The results were staggering. Montgomery crammed roughly 800 men, women, and children on the decks of their gun boats for the return trip to Beaufort.

Montgomery’s expeditions into the interior struck fear in area plantation owners, who were forced to flee further into the interior, often with little warning. Every forced retreat left additional slaves and other valuable property behind. Newspapers throughout the North celebrated his efforts. “This expedition reflects great credit upon Col. Montgomery and the men of his command,” reported the Philadelphia Inquirer. “He has destroyed property of the enemy estimated at a million dollars, proved himself a capable commander, and that the negro troops can be made efficient soldiers.”

His tactics, however, were not without its critics. Higginson described him as a “singular mixture of fanaticism, vanity, and genius. The two colonels could not have been more different. “His hatred of control,” argued Higginson, “makes it hard for him to believe that a regiment which is well drilled can be fit for action.” “He thinks me straight-laced and red-tapish—I think him fitter to command a hundred men than a thousand.” All of this was driven home for Higginson when he learned that Montgomery “had one of his own men shot without trial…for desertion, & was about to shoot two more” before cooler heads prevailed.

Shaw’s initial perceptions of Montgomery were formed by the pair’s brief meeting in Beaufort as well as his conversations with Higginson. “He is an Indian in his mode of warfare,” Shaw shared with his father, “and though I am glad to see something of it, I can’t say I admire it.” In a letter to his mother, Shaw described Montgomery as a “strange compound.” “He allows no swearing or drinking in his regiment & is anti-tobacco—But he burns & destroys wherever he goes with great gusto, & looks as if he had quite a taste for hanging people & throat-cutting whenever a suitable subject offers.”

It is important to point out, given the controversy that would quickly ensue between the two men following the Darien expedition, that Shaw was eager to attach his regiment to Montgomery’s command. He was aware of Montgomery’s mode of warfare, including the destruction of private property, and Shaw had some understanding of Montgomery’s command style and his volatile personality.

Shaw likely witnessed the celebrations in Beaufort among the hundreds of freedmen liberated during the Combahee Raid, who were being sheltered in many of the town’s churches. Just as importantly, the men in the 54th Massachusetts caught a glimpse of the role that they hoped to soon embrace as liberators.

Ultimately, Shaw hoped to get his men into the field “as soon as possible” and he was enthusiastic about doing so, admitting that “Montgomery is a good man to begin under.”

I don’t mean to minimize the concerns expressed by Shaw following the Darien raid, but it should be clear that he knew what he was getting into. Appreciating this is necessary to properly contextualizing Shaw’s deep dissatisfaction with what transpired under Montgomery’s command.

For that, however, you are going to have to wait for the book. :-)

Kevin, The phenomenon of US officers actively seeking out and liberating enslaved people was probably not something that Shaw witnessed while with the 2nd MA. Indeed, it was exceedingly uncommon anywhere in the Army of the Potomac. He must have been struck by the very different world he encountered in SC, intensified, no doubt, by the reality that by 1863, liberated men might become US soldiers (that seems to have been a something that affected officers in Potomac army little if at all, which is explicable in par by he fact that the the army did not receive its first USCTs till the spring of 1864). In any event, I sense that your work on Shaw is going to force all of us working on the relationship of armies and emancipation to reconsider a good many longstanding assumptions. We all look forward to it.

The comments are interesting. One of commenters points out that Shaw would have found attitudes about freedmen and slaves and liberating the enslaved very different in SC as opposed to what he saw in the Army of the Potomac. Call this a glimpse of the blindingly obvious but I am sure those differences existed across the various theaters of the War. The US troops did encounter different attitudes about abolition,freedmen and African-American soldiers depending on where they were. It would be interesting to look at diaries and letters and the like to understand how this might have impacted the soldiers. As I finish this I wonder if someone has

already done such an analysis and I am just late to the awareness