Is the History of Lynching in America a "Divisive Concept"?

Yesterday the United States Senate passed The Emmett Till Antilynching Act. After over 100 years and nearly 200 attempts by Congress, lynchings will now be investigated and prosecuted as a federal hate crime. You may be wondering what took so long.

More specifically, our students may wonder out loud in classrooms across the country today, why it took so long. It raises the question of whether teachers in states that have passed or are considering legislation banning certain discussions about the history of race in America will even address this important piece of legislation and the relevant history behind it.

As Rep. Bobby L. Rush (D-Ill.), who introduced this legislation, explains, lynching has been, “a long-standing and uniquely American weapon of racial terror that has for decades been used to maintain the white hierarchy.”

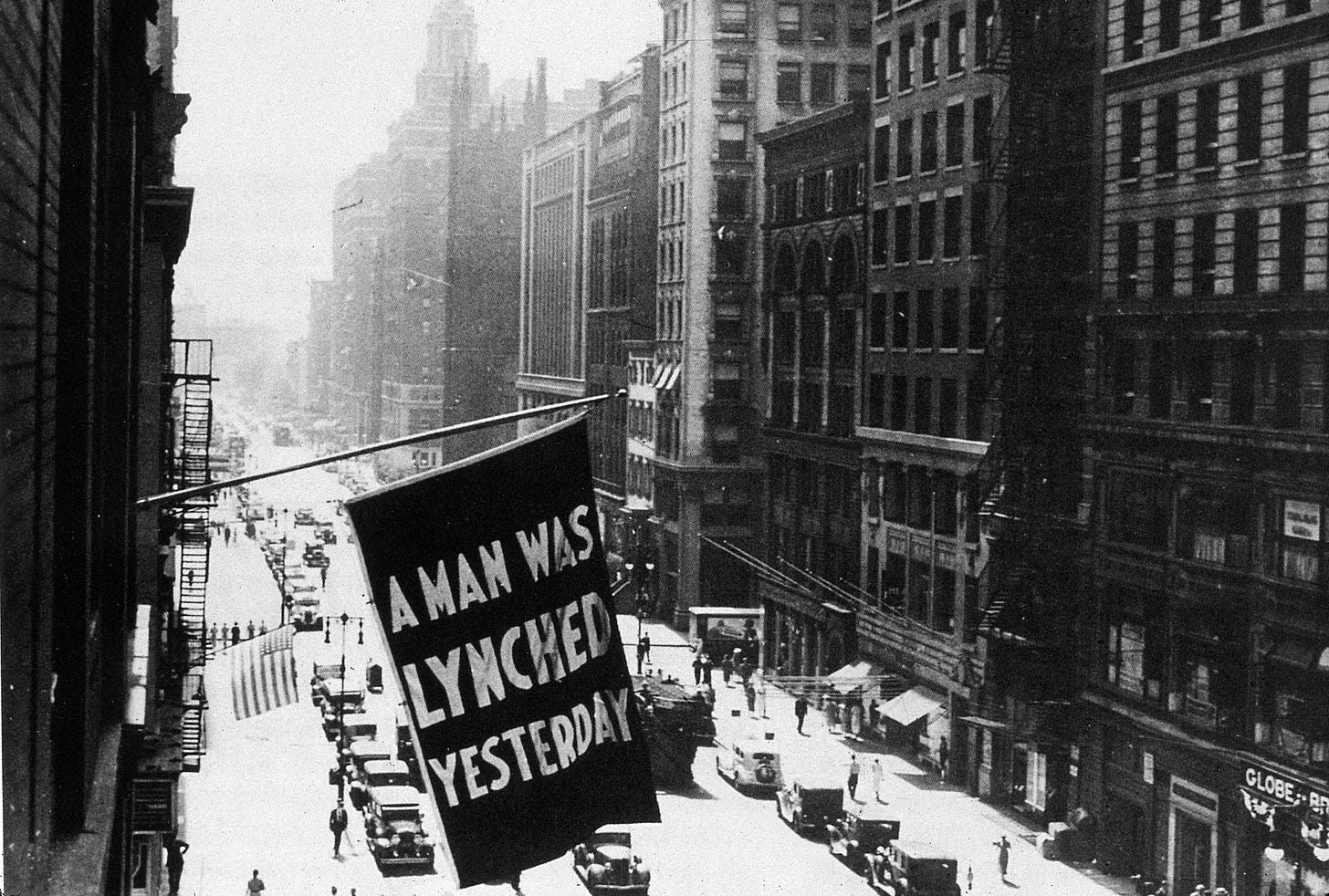

For a historian, there is little, if anything, that is controversial about this assessment, but in the current climate it is toxic. Teachers may not want to risk making their students feel any form of “discomfort” as a result of having to read a newspaper account about a lynching or being shown a photograph of Black bodies hanging from trees in the center of a town square while little white children pose and smile for the camera alongside their families and other residents.

They may worry about the response of a parent whose high school student is introduced to the photograph of Emmett Till’s open coffin that appeared in magazines and newspapers across the country and a grieving mother who ‘wanted the country to see what they did to her son.’

Will this teacher be accused of promoting a “liberal agenda”?

How can we talk about the history of lynchings without exploring the way in which this violence functioned not simply in response to the fear of African Americans, but as a means to maintain a political, cultural, and economic system built around white supremacy? To do so is to challenge the vague language in legislation that a number of states have passed that bans teaching students how one race conceived of itself as superior to another.

To talk about the history of lynchings in America is to talk about “divisive concepts” and even critical race theory’s emphasis on systemic racism.

That it took until 2022 to pass anti-lynching legislation suggests that the border between the present and the past is not as clearly delineated as legislators wish it to be. We are a product of this history. We live with it regardless of whether we understand or are even aware of it.

We desperately need to have these difficult conversations about our history. Teachers deserve the best training to prepare them to engage their students in ways that will allow them to connect the past with the present for themselves in an intellectually and emotionally responsible way.

Teachers will not always get it right, but the direction we are heading in is unsustainable, both for the profession and our ability to learn from the past.

One hundred and twenty years is much too long.