How many times have you heard that the Civil War resonates more in the American South than in any other part of the country? It’s understandable. Over the past few years attention has focused on Confederate monuments, located overwhelmingly in the South.

Going back further, writers such as William Faulkner reminded young Southern boys of the place of the imagination in envisioning a victory at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. Visits to Civil War battlefields are located, almost exclusively, in former Confederate states. Hollywood movies have also contributed to this picture of white Southerners mired in a Lost Cause past.

Even I fell for this meme having lived in central Virginia for 12 years before moving to Boston in 2011.

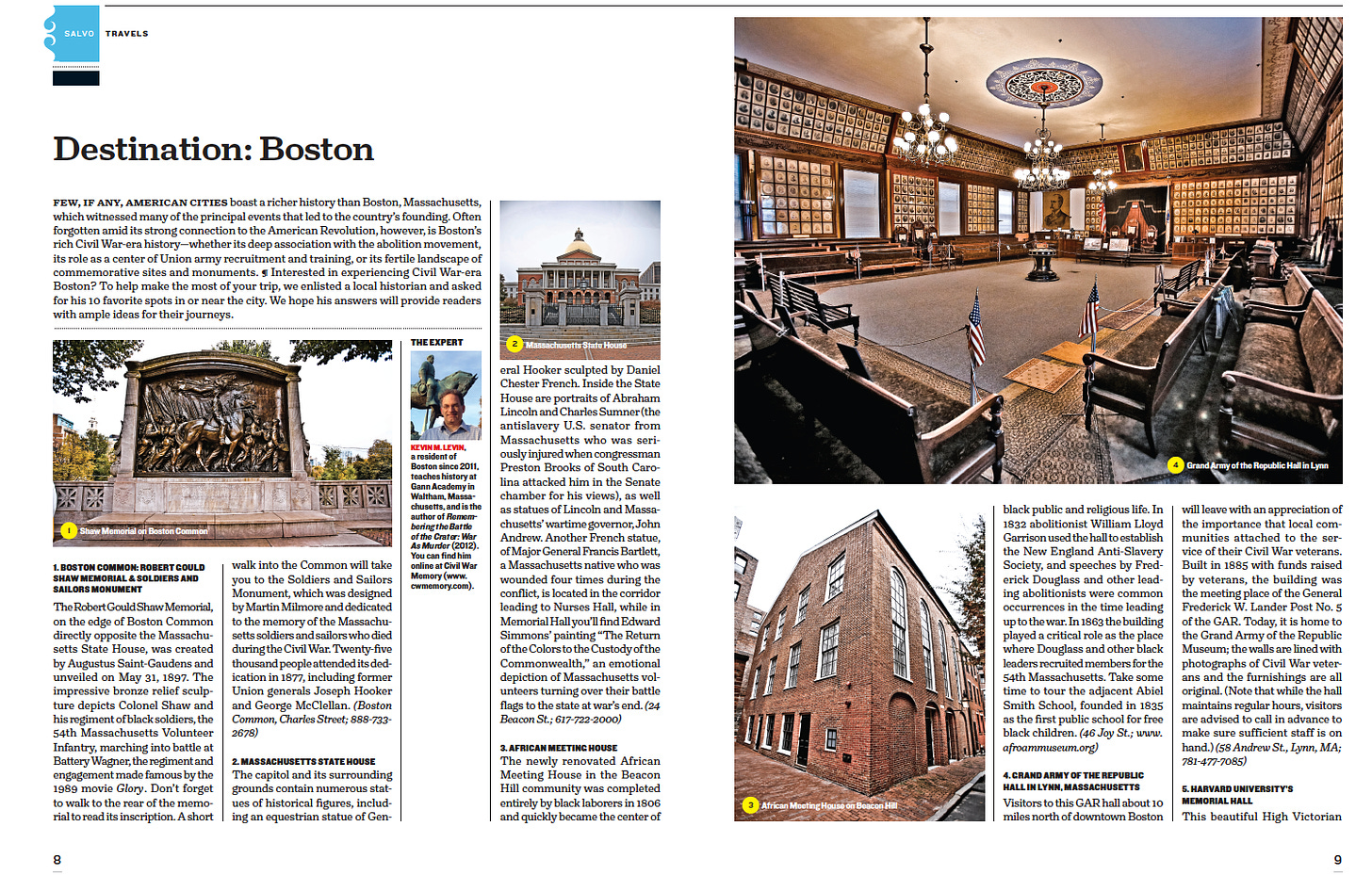

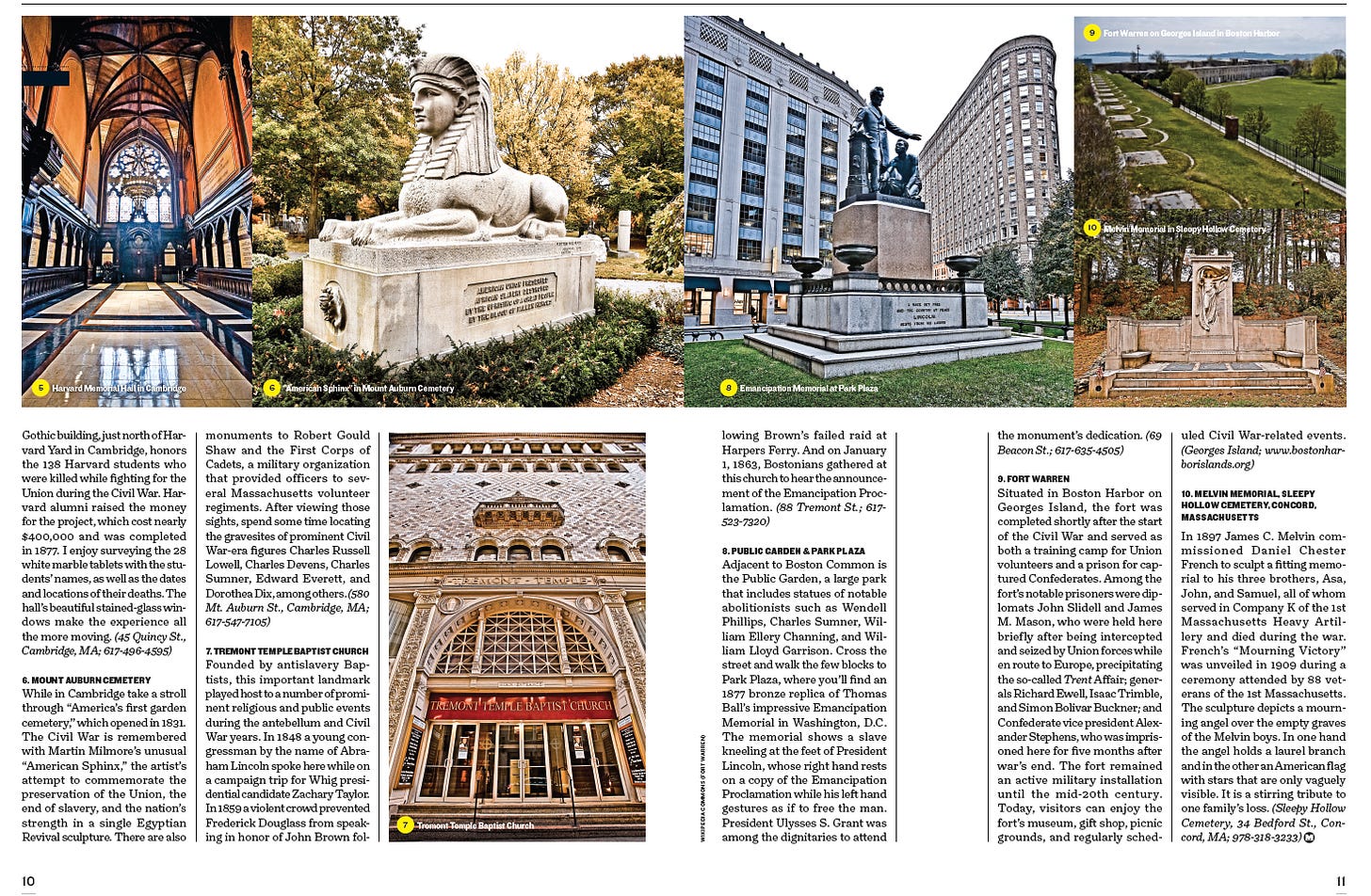

I was quickly disabused of this assumption. In fact, shortly after moving I wrote up a list of places to visit in and around Boston that highlights its rich Civil War memory for the Civil War Monitor magazine.

This list only begins to scratch the surface of the places you can visit.

I guess there is a certain truth to this claim, but all too often it masks the extent to which Americans outside of the South remembered and commemorated the war long after the guns fell silent.

One of the most important points that I try to make when discussing this subject is that memory of the war evolved significantly over time, depending on a host of factors. If we look at the first few decades after the war, one could make the argument that it was white and Black Northerners who took the lead in commemorating the war.

That should come as no surprise given the sting of defeat, federal occupation during Reconstruction, and the overall economic state of the region. In contrast, Black Americans celebrated their role in saving the Union and ending slavery. The vast majority of the loyal white citizenry had every reason to celebrate the preservation of the Union and even the end of slavery—if only because it was believed that it made the nation stronger and would prevent another conflict.

Towns and cities throughout Northern and Midwestern states are littered with monuments and statues of various sizes. Loyal Black and white Americans gathered in cemeteries each and every spring for Decoration Day exercises. Veterans gathered in Grand Army of the Republic camps across the nation, some of which were integrated and included African Americans in leadership positions.

It is impossible to imagine the scale of Civil War battlefield preservation today without the leadership of Union veterans who had an interest in saving these sites for posterity.

I think it is safe to assume that the generation who fought the war—regardless of the side—had an interest in remembering the war and coming to terms with its consequences.

When I think about the differences between how Northerners and Southerners remember the war or the place of the war in each region’s respective collective memory, I tend to interpret it as a product of the drastic changes witnessed in the twentieth century.

By the early twentieth century, the survival of the nation and its gradual involvement in world affairs was an undisputed fact. The nation itself was a reminder of who won the war and what its aged veterans had accomplished. What more needed to be said or done?

In addition, the pace of change in the North and Midwest guaranteed that memory of the war would fade over time.

On the other hand, white Southerners had to negotiate a way back into the fold as loyal Americans, who remained unapologetic about their Lost Cause. Civil War memory had also become wrapped in the broader political challenge of maintaining white supremacy following Reconstruction, which is reflected in many of the monument dedication addresses.

Memory is always informed by the present, but this had become magnified as the generation that fought the war gave way to a new generation that appropriated the past for purposes that had little to do with the 1860s.

This is not in any way intended as a criticism, but simply an observation that historical memory evolves over time.

How do the events of the two decades, including the Civil War 150th and the protests over Civil War monuments, fit into our broader story of Civil War memory? How does it complicate and challenge distinctions and fault lines that have long framed how we think about Civil War memory?

Does it even make sense any longer to talk about regional divides over Civil War memory or for who memory of the war is more palpable?

I should add that one of the most overlooked examples of Civil War memory in the North is its commitment to its veterans through the pension bureau. Its headquarters in Washington, D.C. is itself a celebration of military service and Union.

I grew up a mile from Brandy Station. Even in the ‘70s, buckles and bullets would be turned up by farmers plowing the fields. I knew little about the war in the west. That changed when I moved to Illinois and went to work at a community college. Once my colleagues discovered where I was from, they called me the Belle of the South :-D and began to fill in my education. The memory there hasn’t entirely faded.