Yesterday I sent off my manuscript to The University of North Carolina Press to begin the peer review process. To say that I am relieved would be an understatement. It’s always a strange feeling in the wake of finishing a project that has taken years to complete and one that, at times, has been be both incredibly exhilarating and frustrating. There is still a good deal of work to do. I will eventually have to respond to the two anonymous reviewers, who will read the manuscript for UNC Press. In addition, I need to finalize a list of illustrations and photographs and possibly secure one or two maps for the book.

Thanks to all of you who have supported me along the way. Writing can feel incredibly isolating. Hopping on this site to read your comments and to see the subscription list gradually expand is incredibly satisfying.

As as way of saying thank you I am sharing the introduction to the book. It is very likely to change depending on how the manuscript is reviewed, but hopefully it will give you a sense of where I am going with it. More importantly, I hope it excites those of you who already know something about Shaw as well as those of you who know very little to want to read it.

If all goes as planned, the book should be available by Fall 2025.

Enjoy.

Introduction

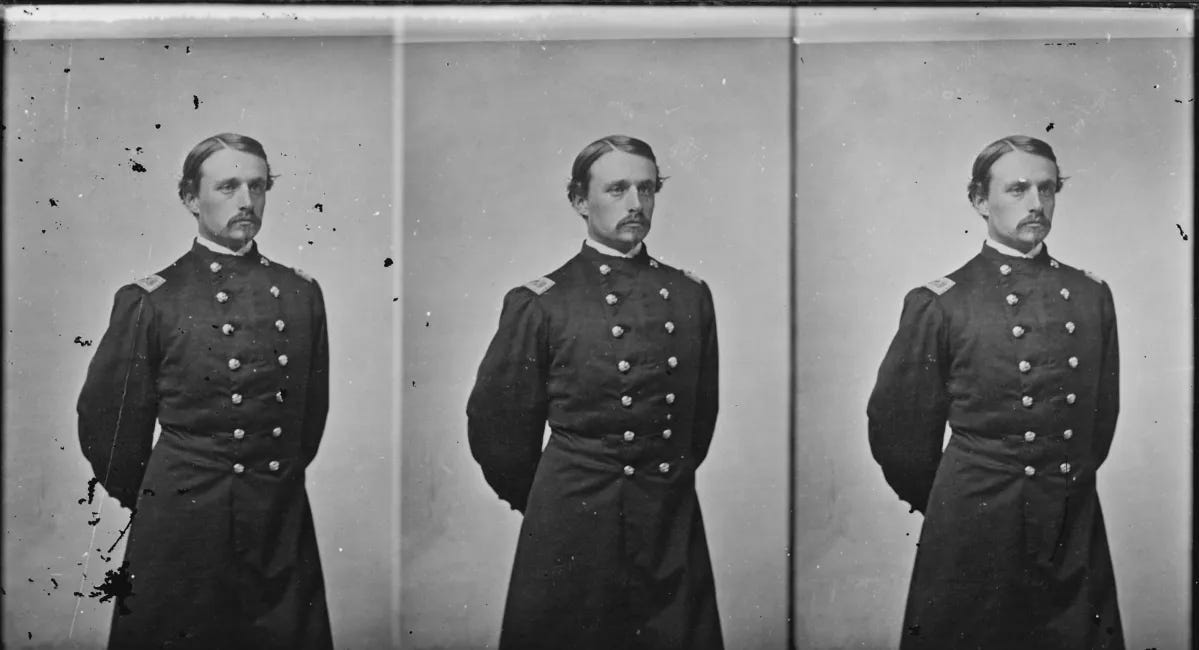

On July 18, 1863, Col. Robert Gould Shaw died while leading the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry—the first regiment of Black soldiers raised in the North during the American Civil War—in an assault against Confederates at Fort Wagner on Morris Island, located at the entrance of Charleston harbor. In the weeks that followed, family friend and fellow reformer Lydia Maria Child penned a tribute for the young officer in the pages of the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Like many of the other memorials published at this time, Child traced Shaw’s bravery, while in command of Black soldiers, and his willingness to give his life to the cause of freedom and racial equality, to his mother and father. “With moral courage beyond all praise,” Child wrote, “they stood side by side with a despised band of reformers” for “the cause of Freedom.” Child included a story in her tribute that she believed constituted a formative moment in the martyred colonel’s short life.

In this story the young Shaw, along with one of his many cousins, sits with his grandfather and namesake shortly before his death in 1853. “My children,” the elder Robert Gould Shaw informed his two grandchildren, “I am leaving this stage of action, and you are entering upon it.” “I exhort you to use your example and influence against intemperance and slavery.”[1] Child’s message was clear. The young man’s embrace of abolitionism and willingness to fight for it on battlefields far from home and ultimately sacrifice his life in the process was no accident, but was nurtured and encouraged at a young age.

It is unclear where Child picked up this family story, but given their close relationship, it is likely that Shaw’s mother, Sarah Blake Sturgis Shaw, shared it with her. This comforting family story aligned Robert Gould Shaw and the rest of his family with the decades-long fight among abolitionists to rid the nation of slavery. Unfortunately, given the timing of his grandfather’s death and the fact that Shaw was, at that time, studying overseas in Europe, it is very unlikely that this intimate and revealing scene between grandfather and grandson ever took place.[2]

But if the story is mere legend, it does shine a light on the divide between history and memory. Shaw emerged from the war as one of three martyrs to the Union cause. The first, Col. Elmer Ellsworth, the charismatic militia commander, who outfitted his men in the colorful uniforms of the French army’s zouaves, served as a rallying cry in the first few months after he was killed by the proprietor of a hotel in Alexandria, Virginia for removing a Confederate flag that flew defiantly on the roof and in full view of the White House in Washington, D.C. On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln died after being shot by actor John Wilkes Booth the previous evening while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre. His martyrdom was secured almost immediately by mourners who were convinced that his death was part of God’s plan to firmly secure the outcome of the four-year conflict, namely the preservation of the Union, for future generations. For Black and white abolitionists, Lincoln’s assassination transformed him into the “Great Emancipator,” who had brought the slaveholding South to its knees and helped to destroy slavery once and for all.

In contrast with Ellsworth and Lincoln, Shaw’s death came in the middle of the war, just weeks after Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. With the outcome of the war still very much in doubt, Shaw was quickly transformed into a martyr for emancipation, the abolition of slavery, and racial equality. Beginning with his family’s refusal to disinter his body from a mass grave on Morris Island, calls to erect a monument in his honor quickly followed. Even before the war ended, Shaw was memorialized by both Black and white Americans in poetry, music, a bust, and mass produced illustrations.

This intense focus on Shaw continued after the war ended in the spring of 1865. Indeed, for decades following his death, Robert Gould Shaw was celebrated and mourned by a wide range of people, including his family, friends, former abolitionists, and veterans of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts. These efforts culminated in 1897 with the dedication of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial, located across from the Massachusetts State House on Beacon Hill. Saint-Gaudens’ detailed and beautiful bas relief placed Shaw on horseback leading his men as it commemorates the regiment’s triumphant parade through the streets of Boston on May 30, 1863, before shipping out to Beaufort, South Carolina and its date with destiny. More than any other commemorative moment during the postwar period, the memorial solidified Shaw’s place alongside his Black soldiers. Their cause had become his own.

Close to 100 years later, the Hollywood movie Glory (1989), directed by Edward Zwick, helped to rekindle interest in Shaw, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts and the broader story of Black military service during the Civil War, which had largely been forgotten for much of the twentieth century, especially among white Americans. The movie benefited from the news surrounding the discovery of the remains of Black soldiers from the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts on Folly Island, located just south of Morris Island, where the Fifty-fourth had fought. The remains of nineteen soldiers, who had died of disease in a hospital, were eventually reinterred in a grave in Beaufort National Cemetery in a ceremony that was attended by Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis shortly before the release of the movie.[3]

It remains one of the most popular Civil War movies owing to its willingness to tackle unsettling issues such as racial discrimination that Black soldiers faced from white soldiers and the very government for which they volunteered to serve. The movie, starring Matthew Broderick as Shaw and featuring Morgan Freeman, Denzell Washington, Cary Elwes, and Andre Braugher tells the story of Shaw’s six months with the regiment, beginning with its organization and training in February 1863 and concluding with the regiment’s fateful assault on Fort Wagner in July.

Like most Hollywood movies set in the past, Glory gets a number of things wrong. Most significantly, the regiment is depicted as made up mainly of fugitive slaves when, in fact, the majority were free-born African Americans from the North. That decision, however, highlights the movies “from slavery to freedom” theme and Shaw’s evolution in coming to identify with and eventually embrace their cause. The movie’s pay crisis scene highlights this point. When the men of the Fifty-fourth learn that they will receive less pay than white soldiers, Trip—a former slave played by Washington—leads his comrades in tearing up their pay vouchers. Shaw’s decision to join the protest by tearing up his own voucher, symbolizes his growing identification with his men and their cause. In another scene, Trip is publicly flogged in front of the regiment after leaving camp without permission to find shoes. Shaw looks on horrified as the Irish drill sergeant carries out the punishment, proscribed by the military, on the former slave.

In the movie’s climactic scene, Shaw leads his regiment in the assault on Fort Wagner, marking their final triumph over adversity and their collective sacrifice around the Stars and Stripes. The regiment’s “glory” not only comes through sacrifice and death, but the movie director’s decision about where and when to end the story. The final scene of Shaw being buried with his men in a mass grave juxtaposed against Saint-Gaudens’ memorial leaves the audience with feelings of national pride and a clear sense that the white officers and Black enlisted men triumphed over their racial differences and willingly gave their lives in a war for freedom and equality.

The film was nominated for five Academy Awards and won three, including Best Supporting Actor for Washington. The movie received positive reviews in The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The New York Times and other major newspapers. Though some critics panned it as a ‘white savior movie,’ Manning Marable, who taught African-American Studies at Columbia University suggested that “the central message” of the film is “Freedom handed down from above to the oppressed, is no freedom at all.” Even a reviewer in Charleston, South Carolina praised the film’s realism and pointed out that it ambitiously tries to portray “several complicated issues.” He described Glory as “must-see film for the Charleston audience.”[4]

Most people, who know anything about the life of Robert Gould Shaw, have likely learned about the young colonel through Glory. It remains one of the most popular Civil War movies and can still be viewed on most streaming services. Unfortunately, anyone wanting to know more about Shaw’s life is confined to two biographies.

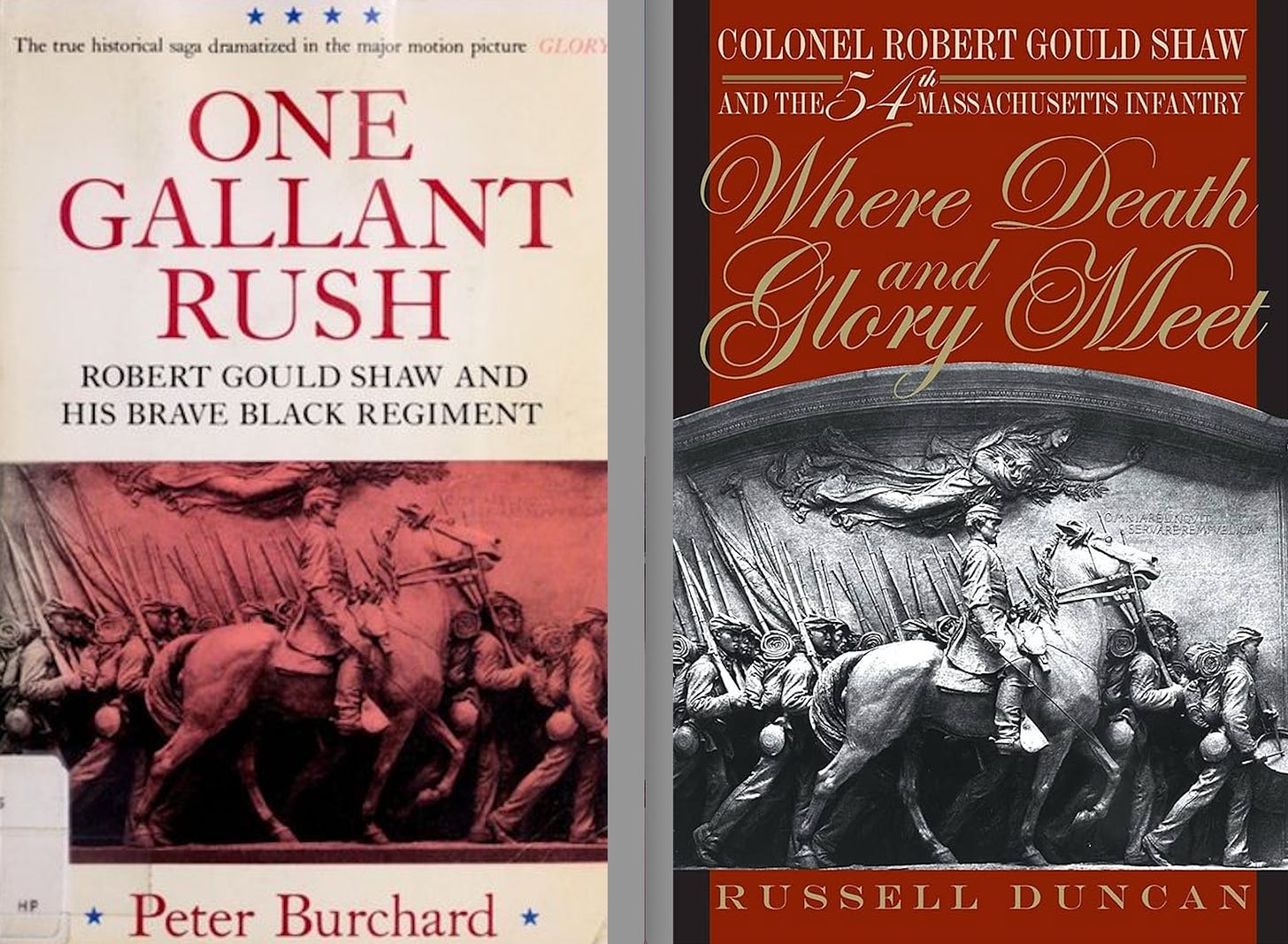

In 1965, Peter Burchard published One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw And His Brave Black Regiment. As author and illustrator of numerous nonfiction books for young adults on topics ranging from Frederick Douglass, Lincoln and slavery to the Underground Railroad, Burchard’s One Gallant Rush was published at the height of the civil rights movement and at the tail end of the Civil War centennial, whose celebrations largely steered clear of references to slavery, emancipation, and Black military service. The book would eventually serve as the inspiration for the screenplay for Glory.

Burchard offers a highly readable and uncritical account of Shaw and his military service with the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, his death solidifying his family’s deep abolitionist ties. “To New Englanders of this own time, Shaw, in his youthful Victorian innocence,” the author writes, “seemed a kind of saint.” “In the last few months of his life, in his latter days and final hours, he had drawn on his forefathers’ deep convictions and sense of duty and his own devotion to the cause which had rekindled the imaginations of New England’s poets and scholars, preachers and teachers and practical men.” According to Burchard, “In his last hours, Shaw had indeed caught fire and to those who had devoted their lives to the breaking of the back of the American shame, his death was an evening and a dawn.”[5]

In 1992, historian Russell Duncan published Shaw’s wartime letters in Blue-Eyed Child of Freedom. His extensive endnotes provide relevant context and Duncan’s thorough introduction, offered a brief, but incredibly thorough overview of Shaw’s life, making this volume an indispensable source on his life and the broader social and cultural world in which he lived. Seven years later, Duncan expanded his introduction from Blue-Eyed Child into what became Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts.

Compared to Burchard, Duncan offers a much more critical assessment of Shaw. Rather than see him as the tragic figure who rushed off to war to fulfill his destiny as a martyr to the abolition of slavery, Duncan offers a more sober assessment: “He did not join the army in 1861 to fight for the Union or to free the slaves, but simply to do his duty. He did not want to avenge the name of his country and to revenge that he considered years of bullying by Southern slaveholders. He did not particularly care if the South was forced back into the Union; he had merely grown tired of the atmosphere of sectional tension that pervaded his daily life.” In the end, according to Duncan, “Shaw craved a nation freed from this disorderly opprobrium so that he could get on with the pleasures of living.”[6] Where Death and Glory Meet effectively challenged the mythology surrounding Shaw as an abolitionist warrior that had been encouraged almost immediately following his death in 1863 and served as a solid foundation for this study.

It should come as no surprise that much of what has been written about Shaw has focused on his command of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts. In addition to the continued popularity of Glory, this narrow focus has been fueled, in recent decades, by a growing public interest in the history of slavery, emancipation, and United States Colored Troops at the same time as the Lost Cause interpretation of the Confederacy continues to diminish in popularity, as evidenced by the debate and removal of Confederate flags and monuments from public spaces. Shaw’s service with the Fifty-fourth and his leadership at Fort Wagner fall neatly into this comforting narrative that celebrates racial progress. Shaw’s death at such an early age and at a point midway through the war removed any possibility of his achievement being overshadowed by his own actions or views concerning the end of slavery in 1865, Reconstruction, and the broader question of equal rights. The result, however, is a skewed understanding of Shaw and his place within the broader history of the Civil War.

Shaw spent roughly five months with the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts in the first half of 1863, but he served for two years, first briefly in the New York Seventh Militia Regiment before transferring to the Second Massachusetts in which he served from May 1861 to February 1863. Apart from the opening scene set at the battle of Antietam, in which Shaw was wounded, Glory completely ignores his prior military career, but it was in those first two years that his understanding of the war evolved.

During that time Shaw first experienced the horrors of battle and the pain of losing close friends. Hundreds, if not thousands, of African Americans took to roads and narrow paths throughout Virginia, forcing officers like Shaw to reflect on their own racial assumptions, emancipation, and the question of whether freed slaves should be enlisted in the army. During those first two years, Shaw confronted not just Confederates in the field, but enraged civilians, who thought little of shooting at “Yankee” soldiers, who they viewed as invaders. Shaw was a seasoned and experienced junior officer by the time he accepted Massachusetts governor John Andrew’s offer to command Black soldiers.

Overlooking or minimizing this portion of his career has had the unintended (and sometimes intended) result of framing Shaw’s acceptance of command of the Fifty-fourth as inevitable. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, it is very likely that if the war had ended before January 1, 1863, without emancipation, Shaw would likely have celebrated its end and looked forward to the opportunity to return to his private pursuits. Unlike his parents, Shaw never fully embraced emancipation and the end of slavery as a wartime goal. His failure to fully embrace the principles of his abolitionist parents led to sharp disagreements on more than one occasion over the first two years of the war, especially following President Lincoln’s release of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation after the Battle of Antietam. In addition, Shaw and his parents clashed over Lincoln’s leadership, controversial generals such as George B. McClellan, and on the personal front, his decision to get engaged to and marry Annie Kneeland Haggerty just weeks before shipping out with the Fifty-fourth at the end of May 1863.

While Shaw insisted that he had a duty to serve his country in its hour of need, he never expressed a deep commitment to any ideological principles. He never identified himself as an abolitionist and this proved to be a constant frustration for his mother long before the war began. More than anything else, Shaw sought advancement in rank and honor on the battlefield. Ultimately, his acceptance of the colonelcy of the Fifty-fourth had more to do with realizing these goals than the embrace of an abolitionist agenda.

It's been over twenty-five years since Duncan’s biography of Shaw was released. That book, along with much of the scholarship published at the time reflected a post-civil rights interpretation that drew a sharp distinction between Northerners, who fought in defense of the Union before embracing emancipation and Southerners, who fought to create a new nation committed to preserving and expanding the institution of slavery and white supremacy. The four years of fighting left roughly 750,000 Americans dead, but the freedom of 4 million Americans rendered the outcome and the “new birth of freedom” it brought about worth it.[7]

The story of Shaw and the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts fit neatly into this “neo-abolitionist” framework. Between 2011 and 2015, the history of United States Colored Troops was front and center during the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War at historic sites and a wide range of public programs throughout the nation. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the Black Union soldier was the face of the Civil War sesquicentennial.[8] The story of Shaw and the Fifty-fourth fit neatly into this interpretive and celebratory framework best captured in the National Park Service’s theme for the 150th: “From Civil War to Civil Rights.”

Yet at the same time scholars increasingly pushed back against this interpretation with what historian Yael Sternhell describes as “an emphatic antiwar stance on the Civil War” that highlights, among other subject, northern atrocities, the violence and disease experienced by enslaved families in contraband camps, and desertion among African American soldiers. Emphasizing the war’s brutality has enriched and complicated our understanding of the war, but at the same time has made it more difficult to pull out anything redeeming about the conflict and its consequences.[9]

The persistent reckoning over American history beginning in the wake of the mass shooting of nine African American churchgoers at the Mother Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston in 2015 and continuing after the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020—much of it centered on the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction—has only complicated the challenge of finding a place for Robert Gould Shaw in the nation’s collective memory.

The history and broader culture wars of the past few years have increasingly coalesced around irreconcilable positions with one side arguing that we should see our national history as a source of pride and the other a source of shame, with one camp rallying around 1619 and the introduction of slavery to the colonies as the rightful foundation of the United States and the other a more traditional date of 1776 and independence from Great Britain. Republicans and conservatives routinely accuse Democrats and liberals of wanting to reduce the past to little more than a story of shameful oppression and white guilt, who in turn accuse the other side of intentionally overlooking slavery and racism in favor of a naïve view of “American Exceptionalism.” Politicians and activists have succeeded in reducing American history to a morality play, one between a story of saints and villains. The overt and intentional politicization of American history leaves little room for complexity and nuance.

Robert Gould Shaw was neither a saint or villain. He sought honor on the battlefield, but he did not set out to take part in a social revolution that would fundamentally transform the nation within a few short years. His short life and even shorter military career offers a small window into this defining moment of American history. Like many people, Shaw struggled to make sense of the dramatic shifts that took place during the first half of the Civil War from the movement of large numbers of enslaved people and armies to the escalating violence that appeared to have no end. Each step forward raised new questions that Shaw struggled to answer and which often placed him at odds with his parents. With hindsight, we can now more clearly discern the myriad and complex ways in which the very movement of freedom seekers across the South, the movement of armies, escalating violence, the continued advocacy of the abolitionist community back home, and his own ambition that helped to place Shaw among a coalition of loosely connected actors that led to emancipation and the eventual abolition of slavery in 1865.

The postwar martyrdom of Shaw transformed him into a symbol of freedom and abolitionism—a position he neither sought or desired. Such a transformation, however, was never necessary to appreciate Shaw’s place in the broader story of the Civil War and American history. The contingency of war led Shaw and the men of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts to that sandy beach on Morris Island and in the moment where his own life and that of the future of the nation hung in the balance he stepped up and answered the call of duty. Shaw did not live to see the results of his labors nor could he have anticipated the many challenges that the nation would confront as a result of the war and Reconstruction. The work of pushing this nation to live up to its founding principles has been nobly advanced by every generation and will most surely continue with the promise of a better future and the echo of marching footsteps of a young colonel and his brave Black regiment.

[1] National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 15, 1863; reprinted in Carolyn L. Karcher ed., A Lydia Maria Child Reader, 267-68.

[2] This story is repeated in Peter Burchard’s book, One Gallant Rush, 5; Joan Waugh was the first historian to point out the lack of evidence for this story. See Unsentimental Reformer, 25, 248 (n. 32).

[3] De’Ann Weimer, “After 126 years, 19 black Union soldiers receive military burial,” May 29, 1989, UPI https://www.upi.com/Archives/1989/05/29/After-126-years-19-black-Union-soldiers-receive-military-burial/7519612417600/ (accessed, March 5, 2024).

[4] Marable quote can be found in “Glory: Controversy, Commemoration, and Indifference in Charleston,” unpublished paper, in Gittleman Research Papers, MHS; Frank Jarrell, The Post and Courier (Charleston), January 12, 1990.

[5] Burchard, One Gallant Rush, 147.

[6] Duncan, Where Death and Glory Meet, 4.

[7] Sternhell, “Revisionism Reinvented?,” 241-42.

[8] See Emmanuel Dabney, Beth Parnicza, and Kevin M. Levin, “Interpreting Race, Slavery and United States Colored Troops at Civil War Battlefields,” 131-48; John M. Rudy, “From Tokenism to True Partnership: The National Park Service’s Shifting Interpretation at the Civil War’s Sesquicentennial,” 61-76.

[9] Sternhell, ‘Revisionism Reinvented?,”242. The essay offers a thorough analysis of the relevant scholarship. Also see, Gannon, Americans Remember Their Civil War, 113-31.

So proud of you.....Dad and Mom

Congratulations on delivering the mansucript! And thansk for sharing this fine intro, which does an excellent job of setting out your approach to your subject. I look forward to acquiring my copy of the final result!

Nitpicking: I think "Denzel" has just one l, and Tripp is, unfortunately, flogged and not "flawed". But these are nits any proofreader would identify.