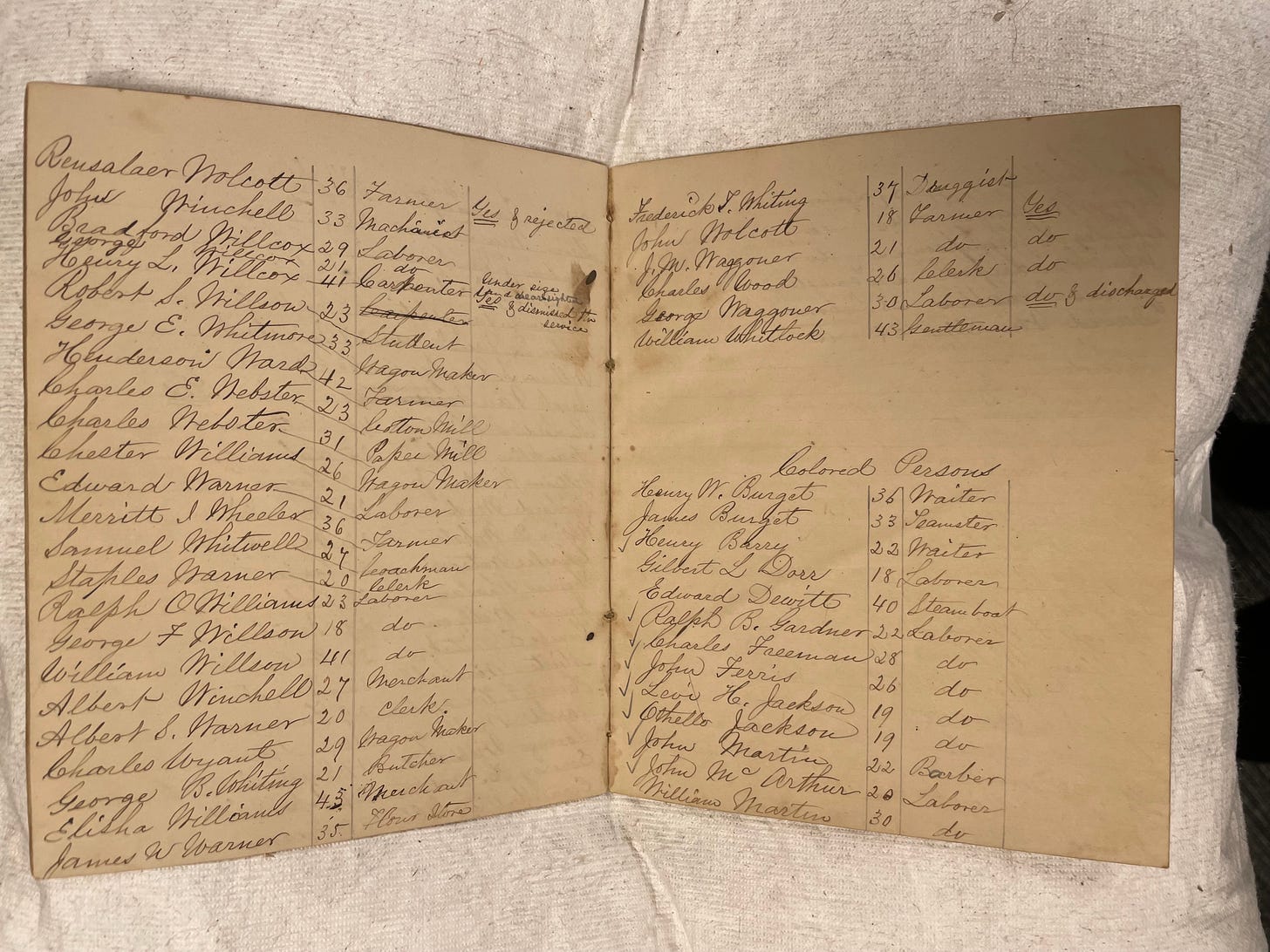

At first glance it’s just a list of names. Page after page of names apparently transcribed by the same hand. Soon you realize that each name tells a story. The list in its entirety tells another story.

On August 4, 1862 President Abraham Lincoln issued another call for volunteers between the ages of 18 and 45. All around the country men volunteered to fight for the Union, including those living in the town of Great Barrington in Berkshire County, Massachusetts.

The historical context is important to beginning to interpret this document. For whatever reason, these men did not volunteer during the rush to volunteer following the bombardment of Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for volunteers in the spring of 1861. The true cost of war had certainly been made apparent to these men and their families by August 1862.

Bloody battles had been fought out west at places like Shiloh in April of that year. By August a series of battles had been fought throughout Virginia. Gen. George McClellan’s attempt to take Richmond had failed and Confederate general Robert E. Lee was beginning his own offensive into northern Virginia and possibly Maryland.

The remote town of Great Barrington was never under threat from Confederate invaders and the men listed in this book likely acknowledged this, but they still answered their nation’s call.

The obvious question: Why? Who are these men and why did they volunteer in August 1862? What regiments did they serve in? How many were wounded or never came home? Are the three Willcox’s listed from the same family? How do the ages of these men compare with the 1861 volunteers?

What did Union mean to these late volunteers? Is there a way to tell whether they were less patriotic? What would that even mean?

No doubt, you already have noticed the fact that the African-American volunteers are listed separately as “Colored Persons.” Do these men descend from families that were once enslaved in Massachusetts?

In what capacity did these men expect to serve? Perhaps they expected to be enlisted as soldiers under the Militia Act of 1862.

I can’t help but wonder if any of these men eventually served in the 54th or 55th Massachusetts Regiments, which were organized the following year. The 54th enlisted a small number of men from western Massachusetts.

What did these men hope to gain as a result of their service? What did Union mean to this small group of African Americans?

This enrollment book would make for an interesting study of volunteers in 1862. I can’t help but think of historian Ken Noe’s wonderful book about Confederate volunteers in 1862. You could focus on this one document or cast your net wider and look at other towns throughout Massachusetts during this same period of time.

There is also something powerful about seeing all these names listed in this particular book. And even though the names are separated based on race, they are all listed together in the same place. Regardless of race, they all willingly answered their nation’s call to service, but their willingness to serve is not the only thing they have in common. Each name points to family and friends left behind, who worried about them and hoped for their safe return.

What questions do you have about this document? How would you go about researching and interpreting it?

Reminder: Beginning on December 1 only paid subscribers will be able to post comments. Upgrade to paid status today. Thank you.

Amazing. I hope someone is taking notes. The literature (as you’ve pointed out previously on Twitter) is sparse on Black men in “integrated” US Army units during the civil war.

Due to the Militia Act, two African American men from Norwell, MA, joined the 45th Mass Malitia, and Lemuel Freeman reinlisted for three years—not in the 54th with his cousins, but with the 58th, another “white” unit. Additionally, the African American community comprised 5% of Norwell’s 1860 population, yet 9% of Norwell’s Civil War veterans were Black.

I wrote about it here: https://eleven-names.com/norwells-lemuel-freeman-integrated-white-civil-war-units/

Do we have any letters from any the people on the list? I took the online course with Prof. Peter Charmichael and initially many of the volunteers had a romantic notion of war which changed as they experienced the horrors of battle. In the course we were able to see that there was a strong sense of Union and Patriotism among people in the North.