I’ve been coming here for years with teachers and other groups, long before it became controversial following the murder of George Floyd, but today will likely be my last visit. The monument is slated to be removed by the end of the year as part of the Naming Commission’s review of military assets that honor the Confederacy.

The site is a wonderful place to interpret the Lost Cause, the pull of sectional reunion, and the nation’s descent into legalized segregation and a Jim Crow culture.

Before hitting the Confederate memorial in Section 16 the teachers that I am working with this week in Washington, D.C. spent time in Section 27, where roughly 1,800 United States Colored Troops are buried as well as 3,800 “civilians” or “citizens” as is indicated on their gravestones. Those designations likely signifiy nothing more than a bureacratic distinction between civlians and soldiers. Many of the African Americans buried here were fugitive slaves who flocked to D.C. after emancipation came in April 1862.

They attempted to construct new lives at Freedmen’s Village on the grounds of Arlington, first operated by the military and later the Freedmen’s Bureau after the war. These men and women did more than look after their families. During Reconstruction they demanded civil rights, including the right to vote, which they exercised after 1867 in and around D.C.

The stories of these people have largely been lost.

From there we walked over to the grave of James Parks, born enslaved on the grounds of Arlington, but worked close to 50 years for the government tending the graves of the dead. His story is told through the demeaning and insulting language of paternalism.

By the time we arrived at Section 16 my group had a visual reminder of the way in which the story of African Americans have been literally pushed to the very boundaries of Arlington. Few people visit Section 27 given its location and no one stops at the Parks marker.

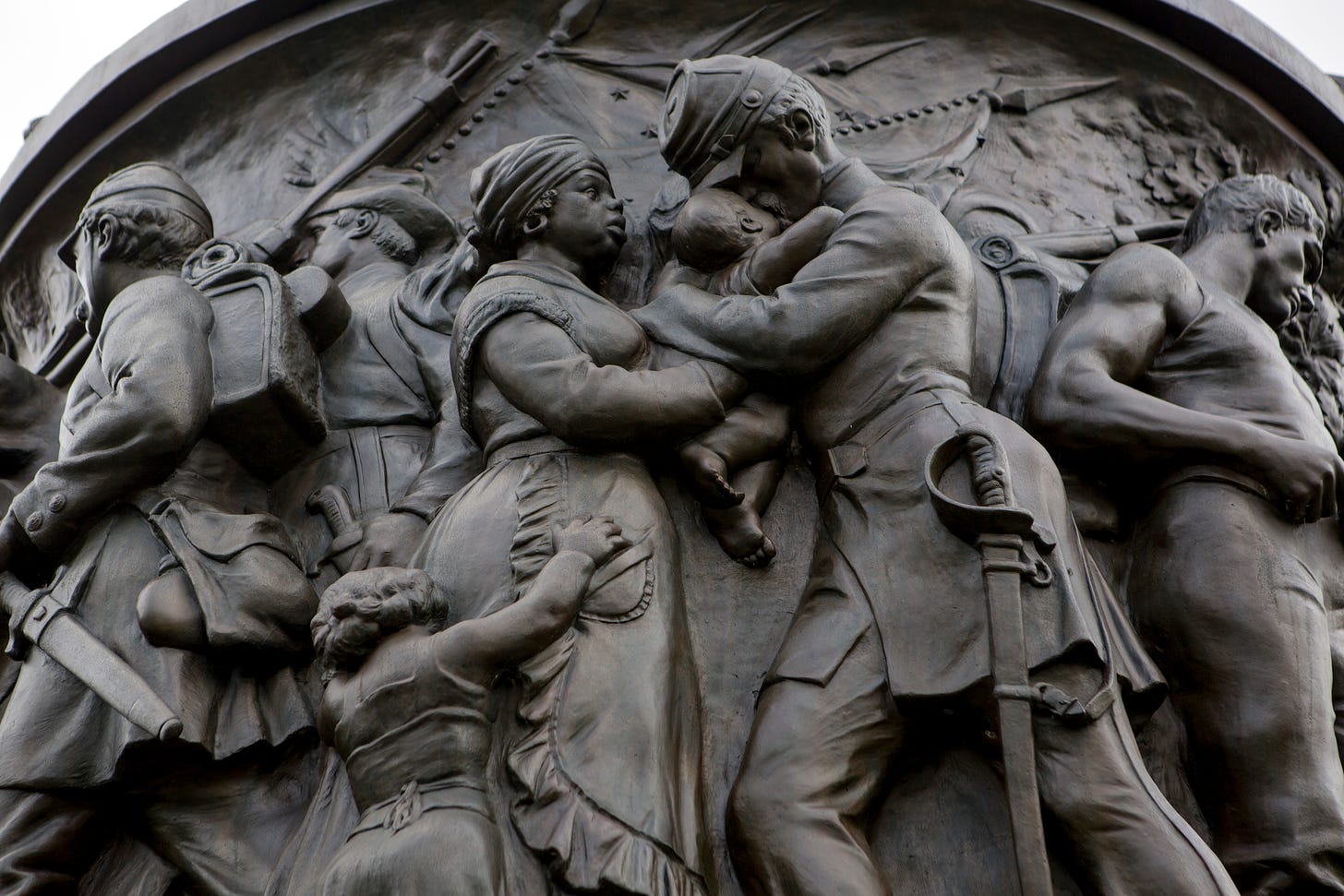

But 265 Confederate soldiers surround the second tallest monument in the entire cemetery. The monument is a unapologetic celebration of the Confederacy. It casts African Americans as loyal to their masters and the Confederacy rather than acknowledging the thousands of African Americans who risked their lives to come to D.C. as refugees in the hope of securing their freedom.

This monument pushes the memory of Black United States soldiers and the collective push for freedom among the enslaved into obscurity.

I am going to miss having the opportunity to interpret this monument, but I understand why it is being removed. It does important work, but this monument was never placed in the middle of a national cemetery for me to use for educational purposes. I am creative enough that I can find plenty of other ways to tell these stories on the grounds of Arlington.

The removal is a reflection of military’s effort to right a wrong and in doing so potentially open up opportunities to tell new stories that have long been pushed aside or ignored entirely.

Can't wait for the big falsehood to give way to smaller truths.

Congress passed a law, over Trump's veto, directing the Department of Defense, to identify and remove, anything that honors the Confederacy, which was identified in the law as made up of traitors.

So the Confederate monument at Arlington is coming down due less to the military's wish than due to the rule of law! I believe 1,111 specific things are being renamed, by the end of 2023, as a result of this law! The military is top-down, and its officers follow orders. Congress passed a law ordering that confederate honorifics be purged. Representative gov't. at work. -- Mark Higbee, Ypsilanti, Michigan