One of the many things that I enjoyed about the civil rights journey that I helped to organize and co-lead last week is the opportunity to to talk about Civil War memory, specifically about Confederate commemoration in cities like Montgomery and Selma.

It’s a chance to talk about them beyond the abstract and really think carefully about the ways in which they functioned on the local landscape throughout much of the twentieth century. Spending time on the ground helps visitors appreciate not just the pervasiveness of Confederate memory, but its role in maintaining a Jim Crow culture. Monuments, street names, building names, etc. were never simply honorific.

They performed a specific role.

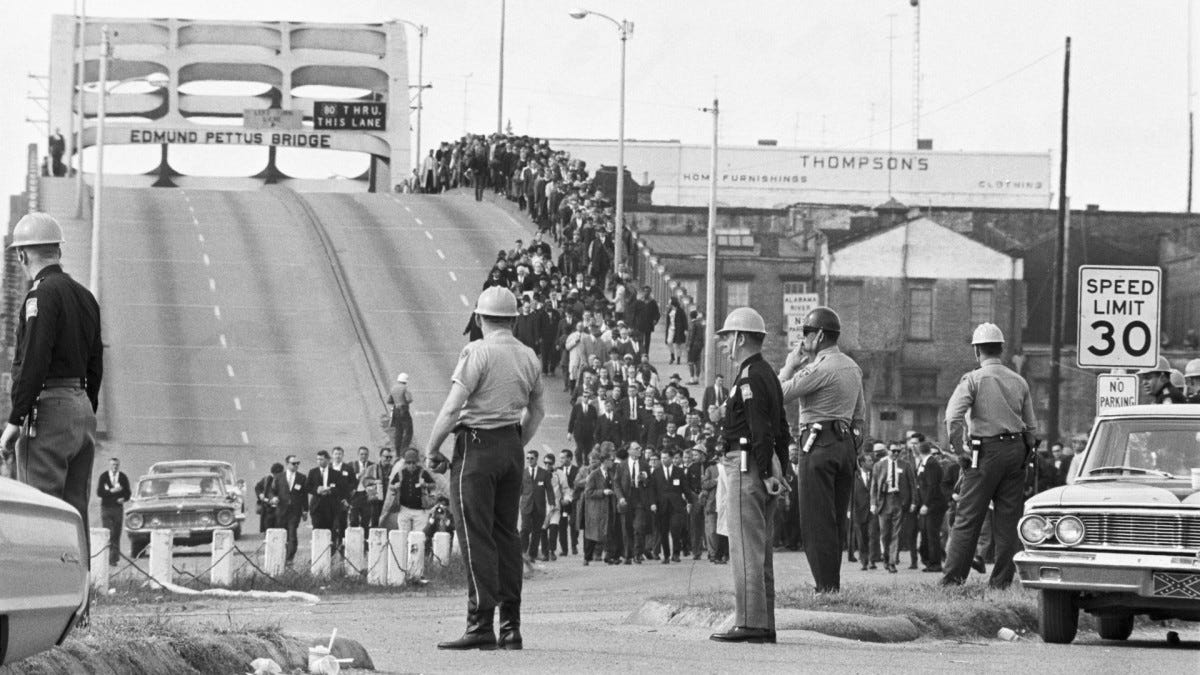

Civil rights activists confronted this landscape head on in there many demonstrations and marches. Selma is a wonderful example. There may be no Confederate soldier statue in the downtown area, but the bridge itself, named after a Confederate general and Alabama Klansman, was a constant reminder of who was in control and the consequences of challenging the racial hierarchy.

On what became known as “Bloody Sunday”—March 7, 1865—civil rights activists literally marched over Edmund Pettus and peacefully confronted police and white vigilantes who were waiting to club them into submission. Law enforcement and much of the white community followed in the footsteps of Pettus that day in their defense of Jim Crow and the racial status quo.

There was a direct line between the Confederacy, the violence perpetrated by the Klan and local authorities on the bridge.

In 2000 Selma residents elected their first Black mayor. Shortly thereafter a group calling itself The Friends of Forrest dedicated a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest—a slave trader, Confederate general, and Klan leader—downtown in front of the Vaughan-Smitherman Historic Building.

The timing was no accident. The dedication of the bust was a form of resistance against racial progress and an argument for the return of white control. The bust was eventually relocated to Live Oak Cemetery. In 2012 the bust was stolen only to be replaced a few years later.

A visit to the cemetery makes it possible to see the current debate over Confederate monuments and memory as a continuation of earlier battles for civil rights. The past and present are almost indistinguishable in such a place.

The culmination of the march to Montgomery on March 21, 1965 offers another powerful opportunity for visitors to see the the way in which monuments helped to reinforce Jim Crow. As the marchers walked up Dexter Avenue, on that final stretch toward the state capitol building, they would have seen the statue of Confederate president Jefferson Davis come into view, which you can see in the photo below.

A star marks the location where Davis swore an oath to defend the constitution of a new slaveholding republic.

To the left of the capitol is the massive 88-foot Confederate monument dedicated in 1898 on the opposite side they would have seen the First White House of the Confederacy, which had been moved to the location in the 1920s.

These monuments and other sites provided a historical argument and justification for white southerners. It tied them to previous generations in one coherent narrative and offered a clear way forward.

They are an important reminder that the push for civil rights and the continuing fight for racial equality is as much about dismantling a certain memory of the past as it is about dismantling the economic and political structures that perpetuate inequality today.

This is the one sense where the argument that removing monuments will result in erasing history makes sense to me. Of course, that in and of itself is not a sufficient argument for maintaining them in situ, but as long as they do exist I will continue to do the work of helping people to better understand them.

Note: I will be publishing another book review on the podcast in the coming days and at the end of the month I will interview historian and Civil War photography expert Garry Adelman. Both are for paid subscribers.