On the morning of April 9, 1865, Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was cut off from its last route of escape at Appomattox Court House. That didn’t prevent him from making one final attempt to break through Union lines in hopes of reaching Lynchburg and eventually linking up with Joseph Johnston’s Confederate army in North Carolina.

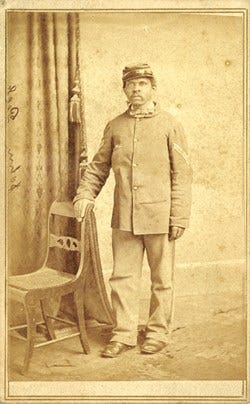

Confederate general John B. Gordon’s men didn’t get very far before they slammed into elements of the Army of the James, which included two regiments of United States Colored Troops. One of those men was John Peck of the 8th USCT.

Brig. Gen. George Crook later recalled watching the Black soldiers form up for what would prove to be the final fight before Lee’s surrender later that day: “We had not proceeded far before we met the…‘Darks’ marching up to the front. I had heard so much pro and con about the fighting qualities of the Negroes that I sent my staff back to reorganize my command while I went along with this corps to see for myself how these people would fight. They were the first I had seen in any numbers….They marched up in splendid order, and although some of them were knocked over, they showed no flinching.”

Born and raised in Meadville, PA, Peck was 22 years old when he enlisted in 1864. He saw action at the battle of Olustee, where he was struck in the head by a saber. A few months later he was grazed by a bullet at the battle of Fort Harrison in September 1864. Though he left the army to recuperate from his wounds in early 1865, Peck managed to return to his regiment in time for the final campaign that resulted in Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Peck and his comrades held their ground that morning. For Lee there was now no other choice but to meet with Grant and discuss terms for surrender.

There were nine USCT regiments present at Appomattox Court House, numbering between 4-5,000 men. Unfortunately, these men have rarely figured in our popular memory of the events surrounding this final engagement and the events surrounding the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia.

After Lee’s surrender, Union leadership moved the Black soldiers away from Confederates to, in the words of historian Caroline Janney, “prevent escalating animosities.” This all but ensured that Black soldiers would not take part in the formal surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia three days later on April 12.

This no doubt upset many of the men, including John Peck. According to historian Elizabeth Varon:

In the eyes of black troops, the fate of the Union was still uncertain on April 9, 1865, and their own agency tipped the scales. They insisted not only that the Union army’s victory emanated from its superior morality and courage and manhood but also that black troops in particular exemplified how military prowess was animated by moral purpose. (p. 99)

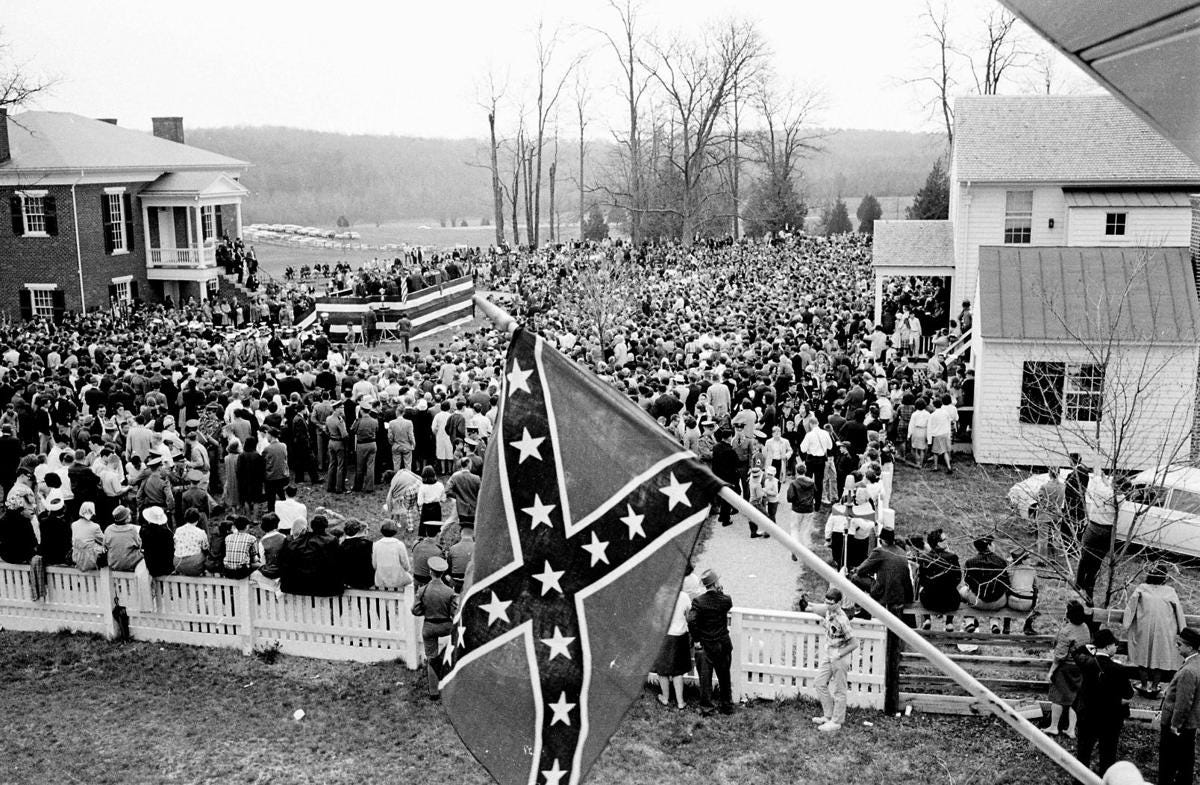

The bigger challenge of recognizing the role of Black soldiers at Appomattox is one of memory. Through much of the twentieth century the events surrounding the surrender Appomattox has been dominated, not surprisingly, by Lee and Grant and a tendency to view what took place as the moment where the seeds of national reunion were planted. The memory of Black soldiers and the broader story of emancipation simply didn’t fit into this consensus narrative.

A sign located in Appomattox says it all, “Where Our Nation Reunited.”

Thankfully, this is beginning to change. The sesquicentennial events that took place at Appomattox back in 2015 offered visitors a much richer interpretation of this history—one that included the story of USCTs and the end of slavery.

This work continues today for the staff at the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park on this 157th anniversary of the surrender. The staff now describes this day as “Freedom Day” in recognition of the significance of Lee’s surrender for the area’s enslaved population.

This is a welcome development, but I sometimes wonder how our memory of Appomattox and the war might have evolved if, at this crucial moment, John Peck and other Black soldiers had been included in the official surrender ceremony on April 12.

How might the illustrations as well as personal and newspaper accounts of USCTs accepting the surrender of Confederate soldiers and the laying down of arms later serve to remind the nation of their role in the campaign and their sacrifice to help save the Union?

I don’t know the answer to this question, but what I do know is that John Peck and others earned this honor.

Amazing story! I had no idea that Black soldiers fought at Appomattox, and especially in such numbers!

Two years ago, I went to an aunt's funeral in Farmsville, VA. Seems as though the Black people I encountered there are very much aware of this history (I am Black.). But they say that Lee's surrender was done the next day to save grace of White Confederates losing to Black soldiers. I am only an armchair historian but I've learned some time ago how "learned" people invalidate the oral history of Black folks (ex: the recollections of the slave quarters at Mt. Vernon.).