In January 2022 the Zinn Education Project published a sobering report on how well the history of Reconstruction is covered in public schools. It should come as no surprise that state standards across the country continue to fall short in a number of ways. We clearly have a long way to go in improving state standards and in devoting sufficient time to teach this important period in American history.

As someone with 20+ years experience teaching American history at the high school level, I believe that the history of Reconstruction (1865-1877) is one of the most consequential periods in our nation’s history.

Few periods in American history are more challenging to learn and especially teach.

According to historian Eric Foner, “the Civil War and Reconstruction is a critical moment in the evolution of American ideas of freedom. But it was a period in which freedom was hotly contested and which different groups of people had very different ideas about what freedom really ought to entail.”

The period witnessed a concerted effort to create a bi-racial democracy unparalleled in American history up to that point as well as a violent backlash that reflected a commitment on the part of many to white supremacy.

The issues at stake could not have been more important as the United States emerged from a costly Civil War that took the lives of 750,000 Americans. In the spring of 1865 the Confederacy lay in ruins and 4 million African Americans had been freed, including roughly 200,000 who had fought to restore the Union and end slavery. Questions that few Americans had ever considered just a few years earlier now needed to be addressed.

How would states that had rebelled against the federal government be brought back into the fold? What should happen to Confederate military and political leaders? What would freedom mean for 4 million formerly enslaved people? What responsibility did the federal government have in reconstructing the rebellious states?

Indeed, what did Reconstruction even mean? Whose Reconstruction?

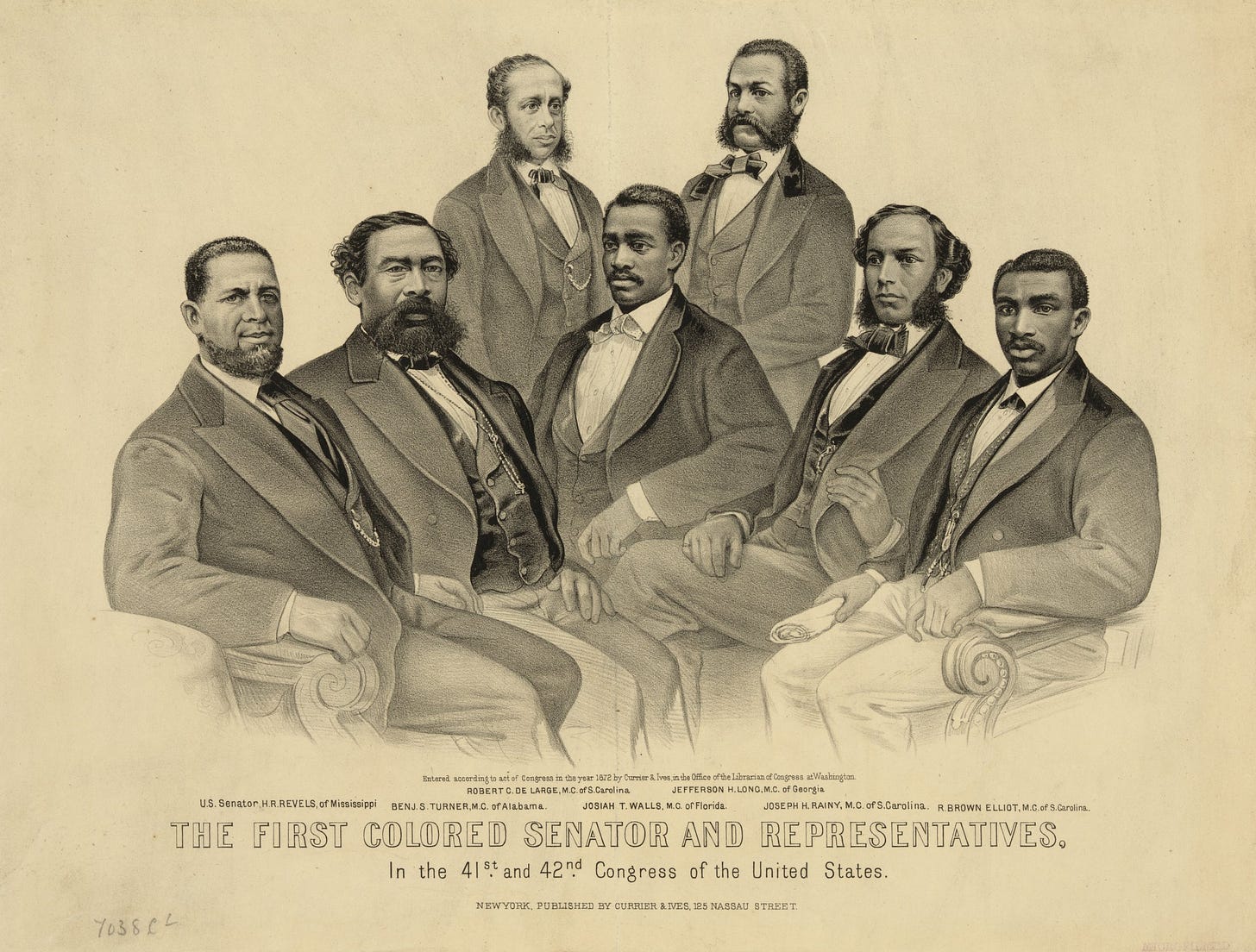

The very question of whose vision of Reconstruction would prevail hung in the balance. Among other things, African Americans pushed for the right to vote and run for office, public education, and land ownership while white Southerners resisted at every step in order to reestablish economic and political control.

Meanwhile, white Northerners debated over the scope of federal involvement in the postwar South and and how far it should go in protecting African Americans against grassroots terrorism.

For teachers this history can be overwhelming, especially for those individuals who are new to the subject. The complexity of this history is matched by more practical considerations such as the amount of time that can be devoted to this period of history within the overall curriculum and the constraints of state SOLs.

It is important to remember that up until recently, the history of Reconstruction was either ignored entirely or taught through a framework that affirmed white supremacist ideology at the turn of the twentieth century. The education system itself has long been complicit in advancing a racist interpretation of Reconstruction that found expression throughout the culture, including popular Hollywood movies such as Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind.

This is something that W.E.B. DuBois understood all too well. In the appendix to his massive study of Reconstruction, published in 1935, he included a sample of how textbooks covered this history.

Although the Negroes were now free, they were also ignorant and unfit to govern themselves. “—Everett Barnes, American History for Grammar Grades

In the legislatures, the Negroes were so ignorant that they could only watch their white leaders — carpetbaggers, and vote aye or no as they were told.—S. E. Forman, Advanced American History

They began to wander about, stealing and plundering. In one week, in a Georgia town, 150 Negroes were arrested for thieving.—Helen F. Giles, How the United States Became a World Power

Generations of students absorbed these racist statements as legitimate history. DuBois understood that this racist interpretation of Reconstruction served to justify a culture of Jim Crow segregation that relegated Africans Americans to second class status, often through the use of state sanctioned violence and grassroots terror.

How Reconstruction is taught has always mattered. How a lesson is conceived and executed can empower students to better understand this history and its legacy or reaffirm long-standing myths and racist tropes that continue to do the work of dividing Americans along the racial line.

Despite the widespread failure to adequately teach the history of Reconstruction, there has never been a more opportune moment to focus on this subject. The scholarship of the past few decades is beginning to make its way into popular textbooks, but more importantly, educators now have a wide range of resources that they can utilize.

The amount of resources available on Reconstruction can be overwhelming even to seasoned educators. One of things I like to remind teachers that I’ve had the opportunity to work with is that no one expects you to master this subject overnight. It takes time. Set out modest goals for yourself.

I make it a point to remind my fellow teachers that we are all students of history. Take the time to read one of the many books on the subject. I recommend, among the many titles available:

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877.

Douglas Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era.

Heather Cox Richardson, West From Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America After the Civil War.

Kidada Williams, I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction. (forthcoming)

Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America's First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction.

For classroom use, organizations like Facing History, Gilder-Lehrman Center, Stanford History Education Group, and Zinn Education Project offer selections of secondary and primary sources as well as lesson plans that can assist teachers.

Teachers now have a wide range of primary sources at their fingertips, which can be accessed, for example, at the Library of Congress and the Freedmen and Southern History Project. State archives, such as this one in South Carolina, also offer more focused digital exhibits on Reconstruction history that can be of use as well.

There are also a number of very good documentaries available, especially Henry Louis Gates’s Reconstruction: America After the Civil War, which aired on PBS in 2019. The series explores the history and legacy of Reconstruction and includes commentary from some of the top scholars in the field.

Professional development opportunities are also available for teachers who want to explore this subject during the summer months. For the past five years I have worked with the incredible staff at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. on a program called Set in Stone: Civil War Memory, Monuments, and Myth, but there are other programs through the Gilder-Lehrman Institute, and NEH that you can explore as well.

One of my favorite approaches to teaching the history of Reconstruction is from a local perspective. Reconstruction impacted communities throughout the South and far beyond. A local approach can introduce students to any number of local leaders who played a role during the period as well as how the community struggled to come to terms with the big issues at stake. Students can read local newspapers through the LOC’s Chronicling America site to explore how this history played out in their own neighborhood or how their community reported what was taking place elsewhere.

Introducing students to Reconstruction can help prepare them to better understand and take part in any number of current issues and public debates.

Over the past few years hundreds of Confederate monuments have been removed and the nation has been embroiled in a divisive debate over how to remember the Civil War era. Many of the monuments that have come down were dedicated in the years after Reconstruction once white southerners had regain control of state governments.

Control of the course of Reconstruction ultimately allowed communities to dictate how history itself would be remembered and commemorated in public spaces such as court houses and public parks through the dedication of monuments, large and small.

All of us are living with the legacy of Reconstruction and as educators we have a responsibility to help our students connect the past and the present.

Questions about voting rights and voter suppression have their roots in Reconstruction. Just today Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson invoked the Fourteenth Amendment in a case about voting rights in Alabama.

The resurgence of racial violence, including the murder of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015 as well as the “Unite the Rally” in Charlottesville, Virginia are a reminder and arguably a continuation of Reconstruction’s violent past.

The recent debate over birthright citizenship is another reminder of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution’s long reach.

Helping students make these connections can be a ‘walk on the slippery rocks.’ In recent years, legislators have passed laws limiting the teaching of the history of slavery and race in America. Teachers rightfully feel intimidated by this increased scrutiny and accusations from parents, politicians and other interest groups that they are encouraging their students to ‘hate their country’ and engaged in other nefarious acts.

No doubt, this environment has hindered many teachers from devoting all their efforts and talents to teaching this difficult history. It is also another reminder that the history of Reconstruction and other periods where race and slavery are central to the story have long been controversial and viewed as a threat.

This should be a rallying cry for history teachers. We must not look the other way or give in to such intimidation. Rather, we should reaffirm our committment to our students and the teaching profession. The best way we can do this is to ensure that every step in our lesson plans and discussions with students are informed by the latest scholarship and clearly articulated curricular goals.

Thank you for another thought provoking blog post. I now have four more open tabs. That is my definition of an educator.

I was an adjunct for many years teaching American history to college students. This is a very good article on an important topic. One thing I would like to add is the popular conception of Ulysses S. Grant, which was often what was taught in school. Grant was in reality an able soldier and an effective general. He did drink, but no more than others of his time. He was the only president to support reconstruction and after his presidency ended in 1877 the South went into the Jim Crow era, only to begin to emerge in the 1960's. The myth of the southern "Lost Cause" had reigned supreme for decades by the 1960's, and still fills a place in popular culture. It is still an important topic.