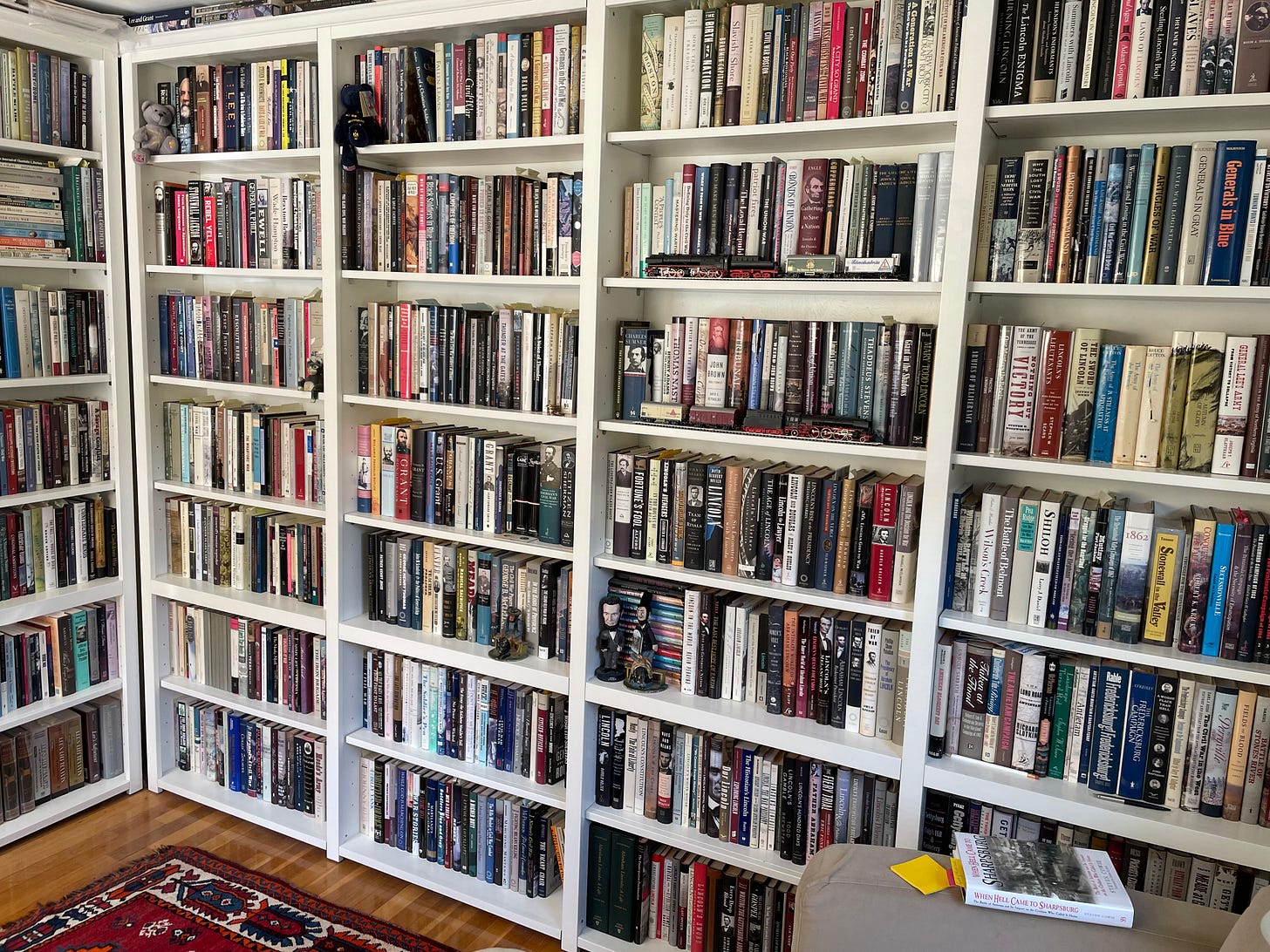

I am a voracious reader. I’ve been reading about the Civil War era for over twenty years and even with everything I have learned there is so much more that I am still trying to understand. My reading is driven by the questions that I want to answer, but even more so by the questions that fuel other historians and writers. Ultimately, I rely on others to help me advance my own knowledge and understanding of this subject.

As curious as I am about the past, I am also vigilant in assessing the work of others. I have little interest in what motivated someone to undertake a particular work of history. What I am interested in is whether a writer can make his/her case for a particular interpretation. This has everything to do with the question[s] that drive a research project, how evidence is collected and interpreted, etc.

In other words, there is a process that can and should be critically evaluated in every work of history produced.

It’s this very personal agenda through which I view the ongoing controvery surrounding AHA president James Sweet’s recent column on the dangers of presentism in the historical profession.

Unfortunately, the media coverage, including today’s op-ed by Bret Stephens in The New York Times, has tended to frame this controversy through the dustup that occurred in response to Sweet’s column, mainly on twitter. It was one of those moments when I was relieved to no longer be on it. People assumed the worst about Sweet, jockeying to be seen and validated while others dueled with one another at the slightest hint of a perceived transgression. It’s so predictable.

I largely vew this as much to do about nothing. Why?

My particular field has long been awash in presentism.

What is the Lost Cause narrative but an interpretation that was driven by the specific needs of white southerners during the post-Civil War period and beyond. Early reconciliationist and emancipationist narratives informed the present as much as they elucidated the past for different groups of Americans.

Every shift in Civil War historiography has been influenced by the culture and politics of the time.

You can’t understand the shift in how historians intepreted slavery in the 1950s [think Stanley Elkins] apart from the experience of Americans in WWII or the increased focus on emancipation in the 1970s apart from the civil rights movement.

These shifts have led to new questions and new interpretations, some of them end up influencing the field and the process continues. The upshot is that our understanding of the past has expanded and deepened, but it has always been shaped by the present.

The influence of the present on how we approach the past is inescapable, but that does not necessarily lead us to relativism. We don’t have to throw our hands in the air and give up on producing a body of historical knowledge. We still have the ability to critique scholarship and other forms of writing.

My problem with Sweet’s column is not that he raised the issue of presentism, but that he appeared to be suggesting that historians can somehow escape it in pursuit of some “noble dream” of objectivity.

Accusing people of falling victim to presentism sounds a lot like accusations of political correctness. I’ve been accused of both throughout my writing career, but ultimately it tells us next to nothing about any individual work of scholarship or other interpretation of the past and everything about the person making the accusation.

As I like to remind my students: Show, don’t tell.

This is where Sweet missed his target. Instead of shedding light on what historians actually do when researching, writing, and reviewing the work of others, he went after a journalist and the interpretation of a historic site in Africa. It was a missed opportunity if ever there was one, especially for the president of the AHA.

Are historians who work in specific areas too invested in current political debates and discussions about race and not focused enough on the time and place in which they study?

I will leave it to others to answer this question. I have to get back to finishing a really good book.

I think much of the problem rests on the fact that for many people the military history of the ACW is divorced from its political and social contexts. This enables a romantic view of the war as being a contest between two principled opponents; both believing that its side was honoring the intent and heritage of the Founders.

Yet, readers here know that one cannot hope to understand the thrust and jab of military strategy and concomitant operations without knowing the politics and how it shaped the attitudes and decisions of both commanders and their political masters. The crucial social context should be obvious when we examine soldiers’ experiences.

For me, that divide in understanding drives a lot of the distortion when folks fix their gaze on the war.

I learned very early that we all wear glasses rhrough which we see the world and history. The trick is knowing what makes up those lenses, language, culture, ethics, etc. This is what makes history fun and interesting. Trying to put yourself in the shoes of others in a differ time to better understand them.