It can be a challenge trying to come to terms with the scale of loss that resulted from the American Civil War. We often rely on numbers to do this work, such as the staggering number of 750,000 dead that the war produced between 1861 and 1865. We might recite the number of dead and wounded at Antietam, still the single bloodiest day in American history or recite the grizzly statistics from any number of other battles.

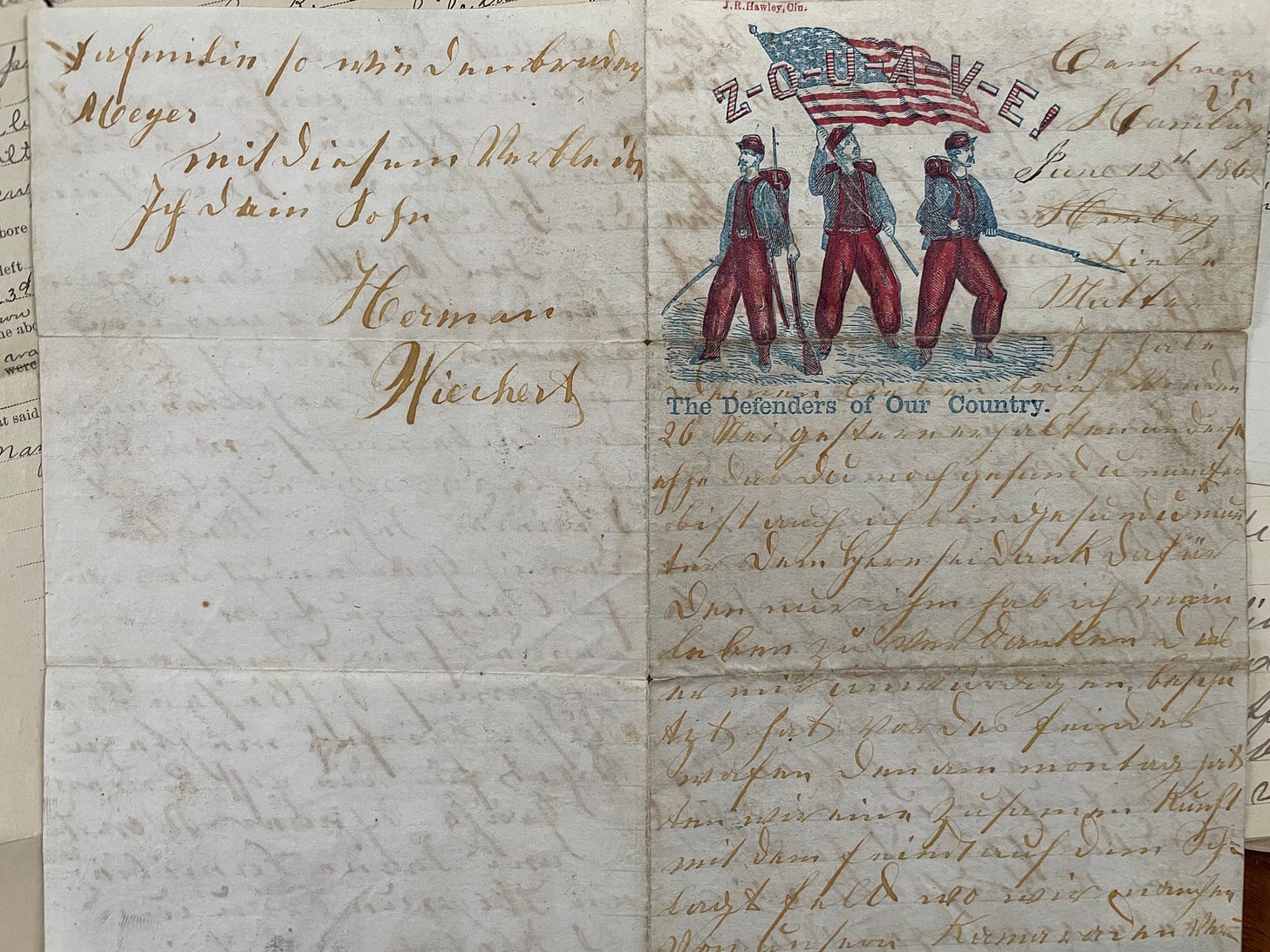

We can attempt to catch a glimpse of it by reading the letters and diaries that soldiers kept to track their experiences for their own future reference and that of their loved ones.

Rarely, however, do we think about scale of loss that families continued to experience long after the war ended. Those experiences are much more difficult to follow as the years passed and the generation that fought the war began to recede into the distant past.

But if we know where to look, we might catch a glimpse of it. With that in mind, here is one family’s story built around a small cache of documents that recently came into my possession.

On June 19, 1861, Henry Wiechert, who was likely living with his parents in Campbell County Kentucky, crossed the Ohio River and joined Co. K of the 5th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Born in Prussia (present day Germany), Henry was 22 years old in 1861.

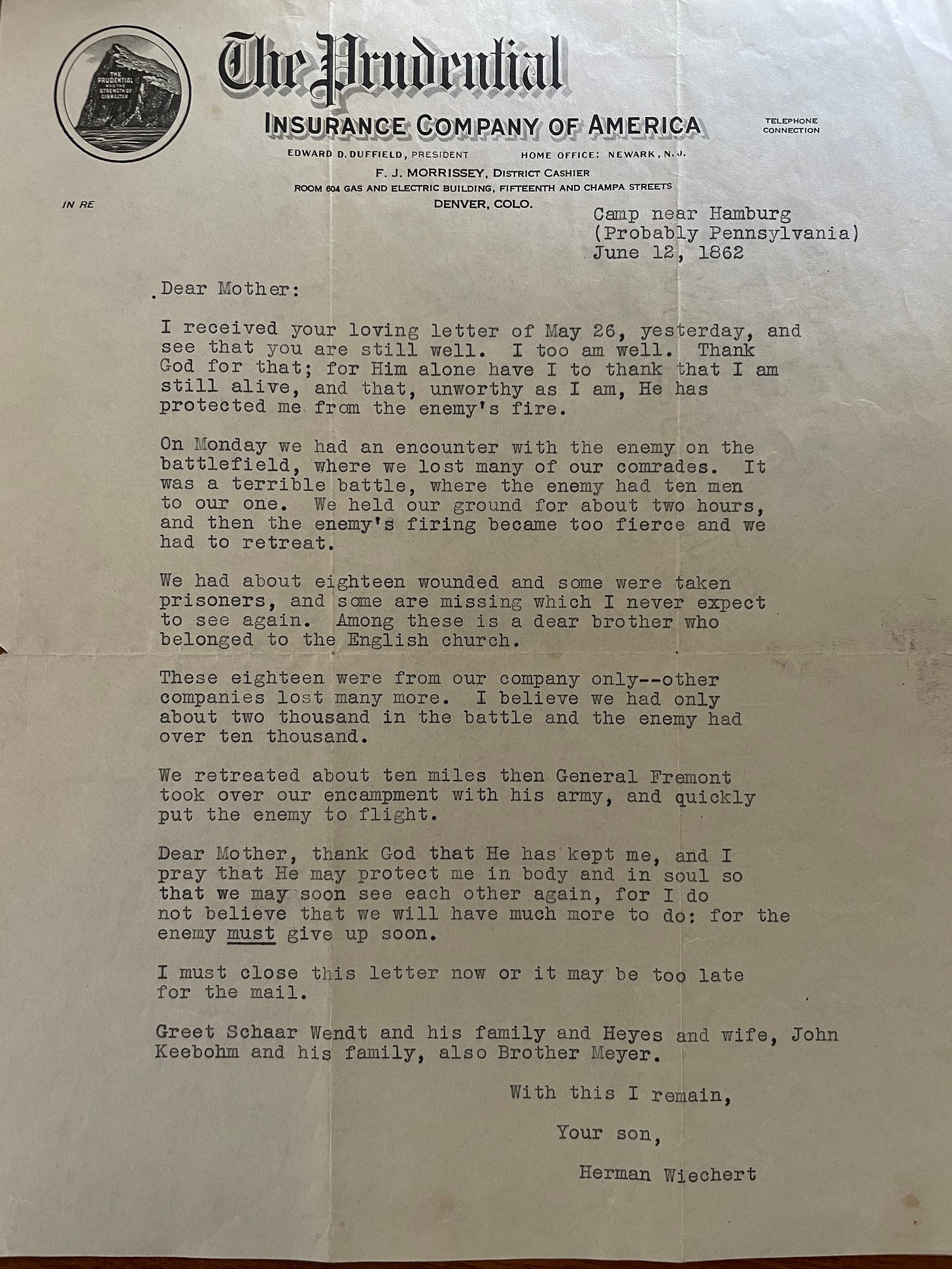

The regiment served in western Virginia throughout 1861, but was transferred to the Shenandoah Valley, where they fought under the command of Gen. John Fremont. Wiechert likely wrote home often, but unfortunately it appears that only one letter has survived. More on this in a bit.

On June 9, 1862 the regiment fought at the Battle of Port Republic. Three days later he penned a letter home (in German) to inform his parents that he was alive and well. Henry characterized the experience as a “terrible battle.” “We held our ground for about two hours, and then the enemy’s firing became too fierce and we had to retreat.”

“Dear Mother, thank God that He has kept me, and I pray that He may protect me in body and in soul so that we may soon see each other again, for I do not believe that we will have much more to do: for the enemy must give up soon.”

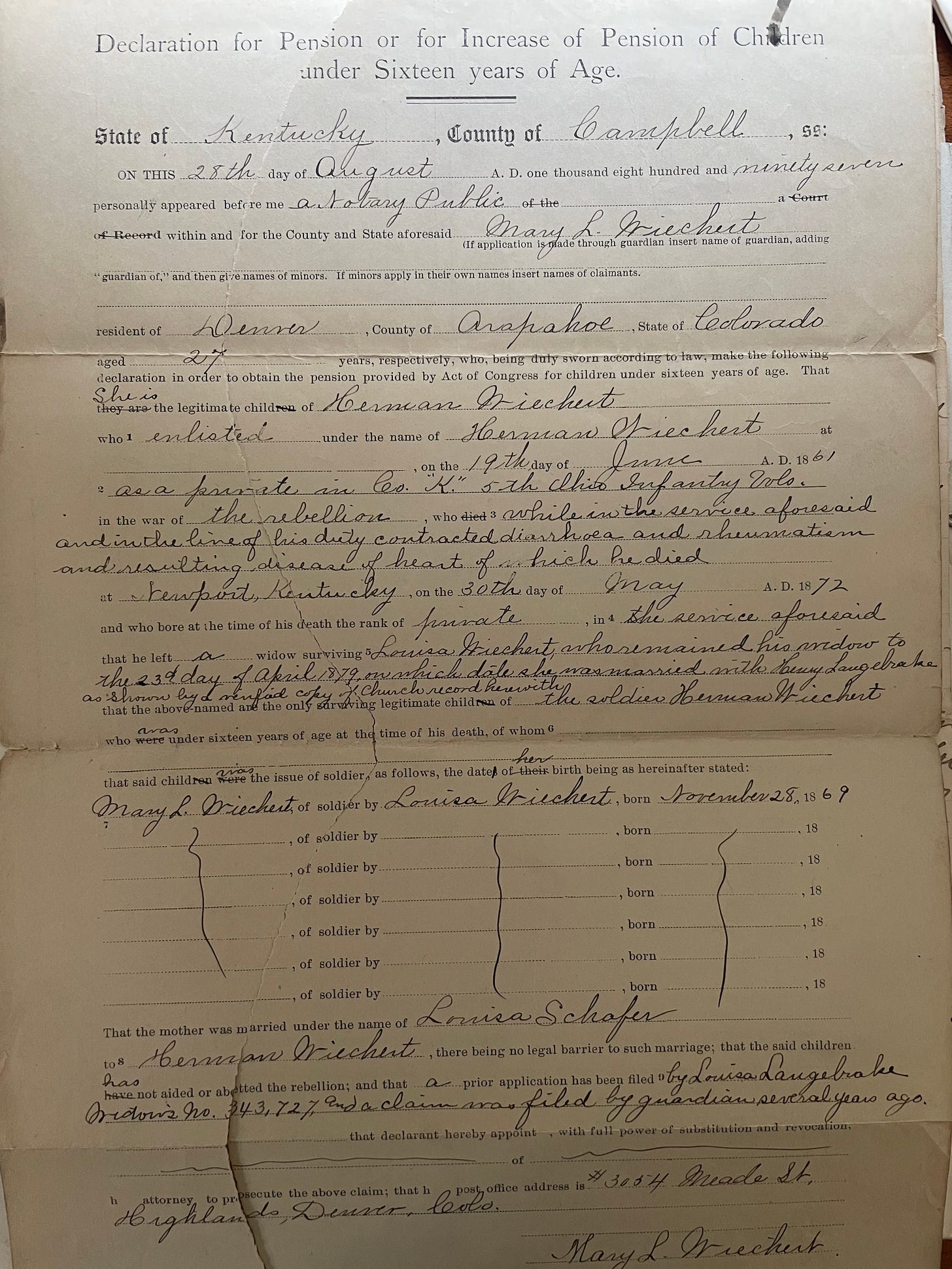

The 5th Ohio went on to fight at Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg before being transferred to Gen. Joseph Hooker’s XX Corps. At some point during the war, perhaps around the time of the Battle of Lookout Mountain, near Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1863, Wiechert was discharged from the army after contracting “diarrhoea [sic] and rheumatism.”

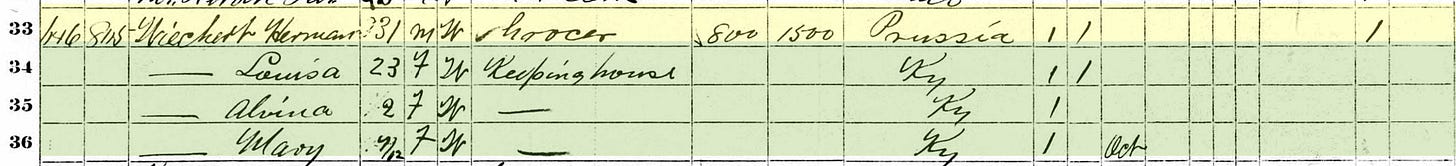

I found Henry in the 1870 census, still living in Campbell County, Kentucky and now married to a woman named Louise (maiden name, Schafer) with two daughters, Alvina, aged 2 and Mary, seven months old.

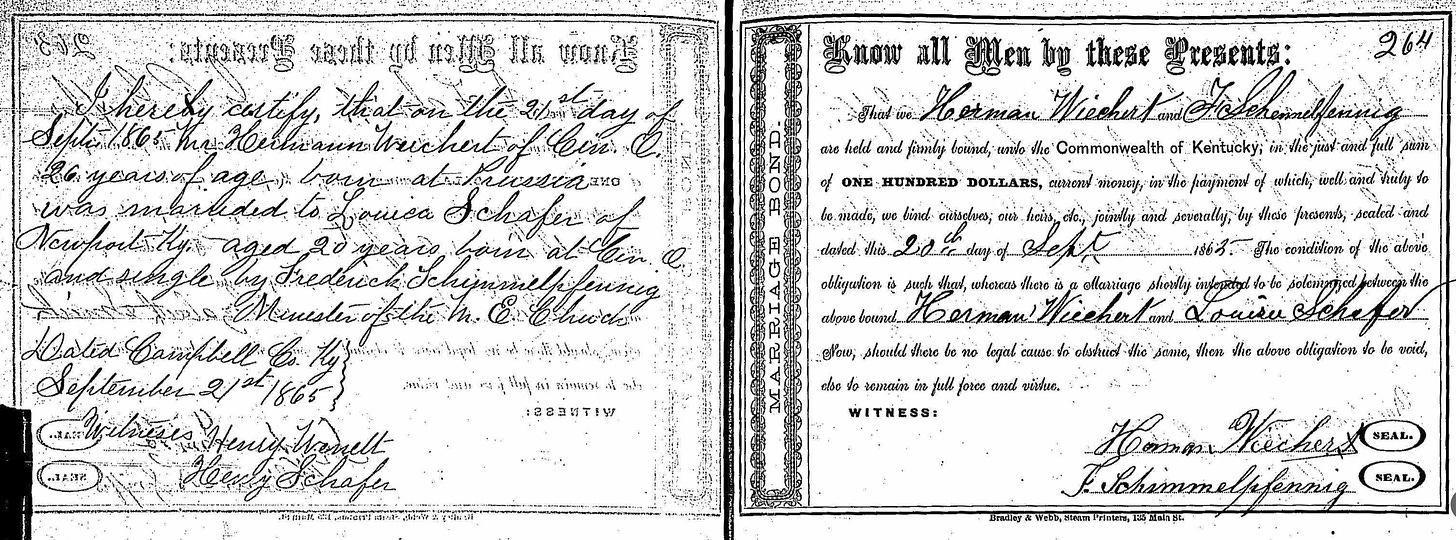

Henry and Louise, eight years his junior, were married on September 21, 1865. Though Louise was born in Kentucky, her parents were from Prussia, which suggests that the two families may have known one another going back before the war. Henry is listed as a “grocer” and Louise as “keeping house.”

I can’t help but imagine what the future looked like from the vantage point of this young couple. Henry had survived the war, started a family with Louise and amassed wealth, both personal and real estate, estimated at $2300. The future must have looked promising for the young couple.

But it was not to be.

Henry died on May 30, 1872 in Newport Kentucky, owing to the complications he experienced during the war.

Looking back we can more clearly discern that the war never really ended for Henry Wiechert and his family. And it never would truly end. Henry was as much a casualty of war as anyone who died on the killing fields of Gettysburg, Petersburg, Franklin and countless other battlefields. Like any family who lost a loved one during the war, Louise and her children were now left to pick up the pieces and somehow move on.

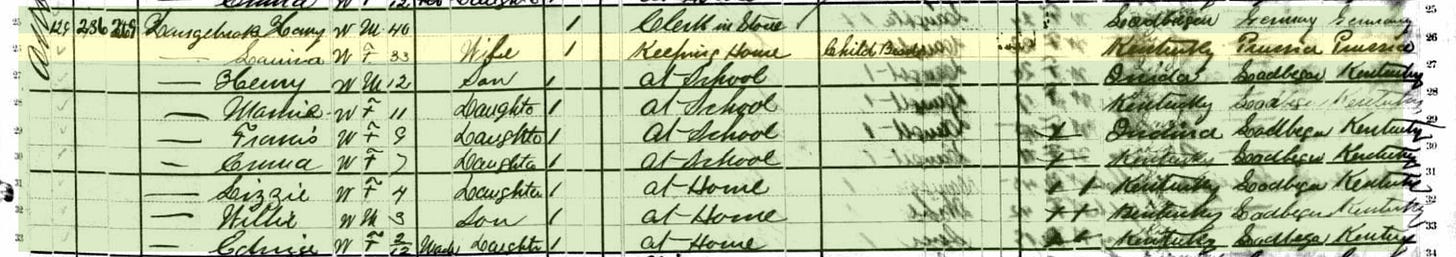

Louise eventually married another Civil War veteran by the name of Henry Langebrake on April 23, 1879. Henry was born in 1840. After the Civil War he worked as a clerk. The 1880 census shows the couple still living in Campbell County, Kentucky with seven children.

Louise’s daughter Mary is now listed as Mamie, but their second daughter Alvina is no longer listed. Henry’s four daughters and two sons were all likely the result of an earlier marriage that ended with their mother’s untimely death.

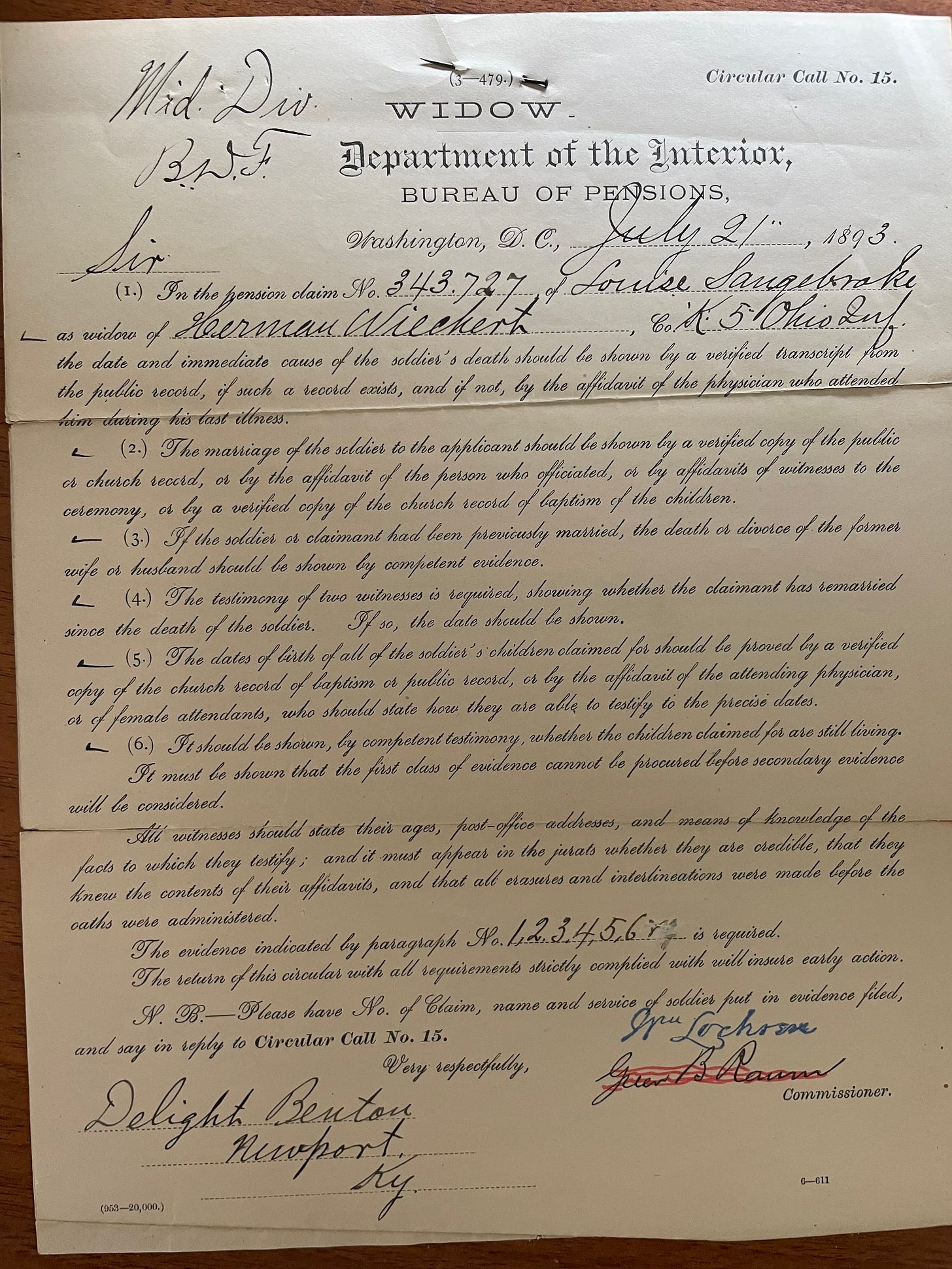

Marriage for Louise would have been absolutely necessary, both for economic reasons and as a means to maintain some level of stability for her children following her first husband’s death. In 1893, Louise also applied for a widow’s pension to help make ends meet.

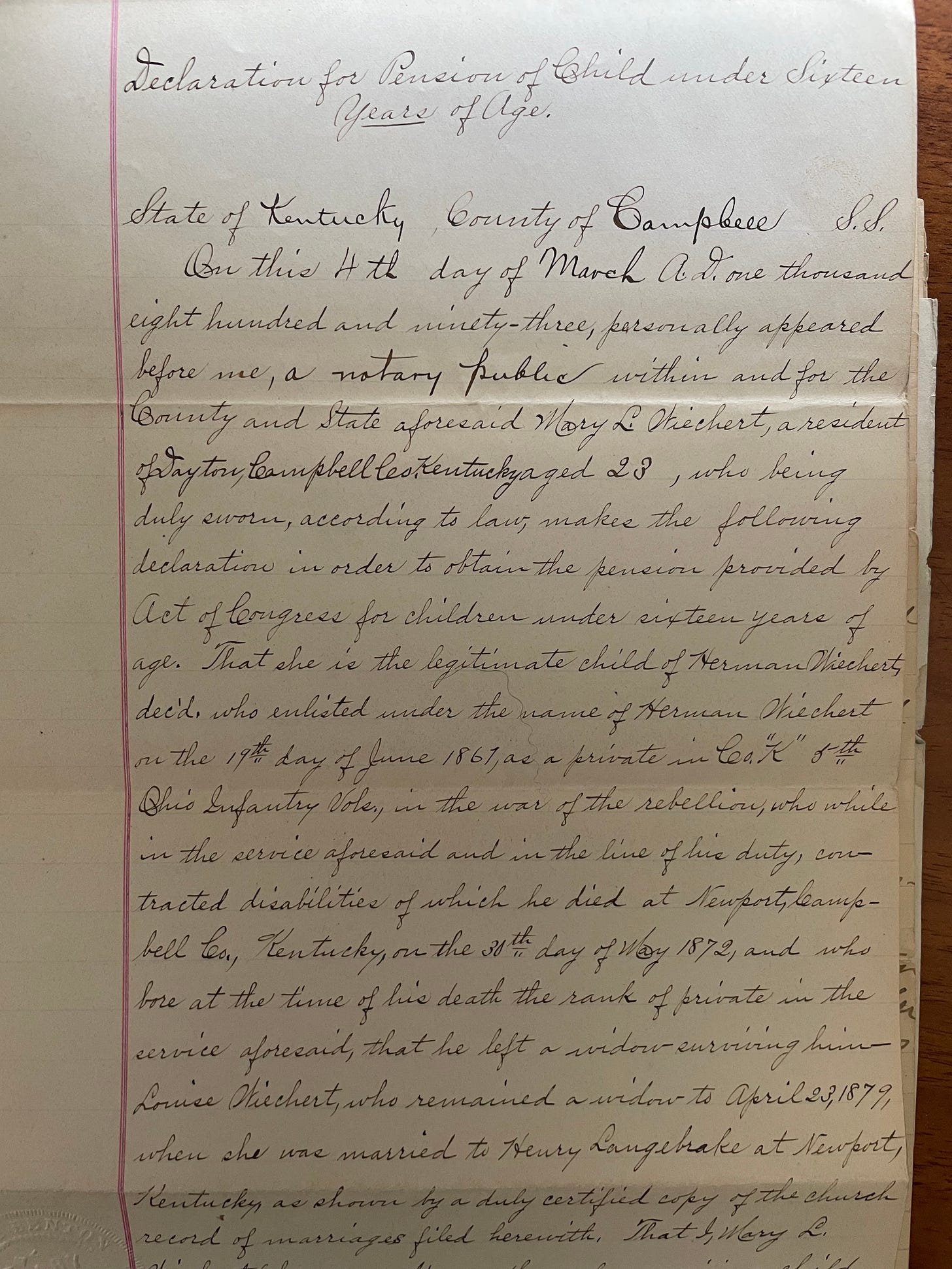

That same year her daughter Mary also applied for a pension for children who were under the age of sixteen before their father died, either during or after the war. She first visited a notary public in her home town, which included detailing the service of her father and securing witnesses to testify on her behalf.

Four years later, Mary filled out the pension application. By then she was living in Denver, Colorado, where she worked as a teacher and later as a stenographer.

Mary also included a transcription of the 1862 letter referenced above as additional proof of her father’s military service.

In addition to the pension claim, Mary secured three witnesses, who could verify her parent’s marriage, her father’s military service and the pain that Henry endured after his discharge. One family friend testified that, “For a month next prior to his death he had great pain and cramps in his body and limbs and his fingers were drawn.”

John Rosser, who served with Henry in the 5th Ohio struggled to recall all the details of Henry’s illness, but he went out of his way to reassure Mary of one thing: “There is one thing I can say as regards your Father. he was a good soldier and did his duty well at all times and under all circumstances.”

These documents can tell us quite a bit about the military service of men like Henry Wiechert. They also shed light on the postwar transformation in the relationship between citizens and the federal government, one that obligated the latter to care for its veterans and their families.

But these documents also tell us something about the profound sense of loss that long outlived the war. Henry’s death must have been a staggering blow to Louise just as they just started to build a life together. By all appearances, it looks as if she managed to pick up the pieces as did countless widows of fallen soldiers and veterans throughout the nation.

In the case of Mary, I can’t help but wonder what she thought as she filled out these documents and read the affidavits of individuals that knew her father in war as well as back home in Kentucky. After all, she likely had few, if any, memories of her father.

What did Mary think when she read Rosser’s account of her father’s service in the war? Was it the story of a complete stranger or was there a thread of emotional connection?

Was the pension process simply a means of income or did she see it as an opportunity to inscribe his story into an official record as evidence that he served and ultimately gave his life for his country?

We often talk of Civil War memory as something abstract, but the story that begins to emerge from these documents point to a more visceral and perhaps even painful personal memory built, not so much around what once was, but what might have been.

I recently read "Letters to Lizzie: The Story of Sixteen Men in the Civil War and the Woman Who Connected Them All" who lived in my area in southern NJ during the civil war. It is the first time I have read so many letters connecting a group of people in the war. Very interesting and at time heart wrenching. The author did do research to provide information, as much as possible, post war.

Your article really brings out the other side of the men that fought and thier families.

Thanks.

Mike

PS, I mentioned a couple of weeks ago I was taking my 2 granddaughters to Gettysburg. They absolutely enjoyed the trip. I was pleasantly suprised at how much they wanted to see and do. It had been about 25 years for me since being there and they have done a great job with the battlefield and area.

Scharr usually appears as a proper name. Schar when applied to sheep means a flock. Schaar refers to scissors. Wendt is a person of Wendish or Slavic extraction as are many of those German speakers from the Lausitz region of Saxony which still exists as the southern and eastern most state in the former East Germany and a holdover in Post-Reunification Germany. Saxony bisects Germany diagonally when considered as an extension of Niedersachsen and Saxony-AnhaIt. I suspect my Civil War ancestor of deriving from the city of Goerlitz as a product of the Treaty of Westphalia that ended (at least officially) the Thirty Years War. Scharr Scharr Scharr, Schar Schar Schar, Schaar Xie Schaar Xie Schaar Xie Schugartown. A little joke between me and my Mandarin teacher. Xie Xie.