Finding a Place in the Complexity and Confusion of the Past

We want our historical narratives to resolve with a clearly discernible meaning. What form that resolution takes depends on a host of factors that we bring to our understanding of the past. For some, it is the vindication in the belief that freedom is continually expanding and that it enjoys a special place in the history of the United States. For others, it might be a skepticism about the history of this nation, rooted in the painful history of white supremacy and the legacy of slavery.

So much of our public discourse about American history these days seems to revolve around these two poles: American Exceptionalism v. ‘Stamped from the Beginning.’

We need to move beyond this to a point where we can acknowledge the complexity and confusion of the past.

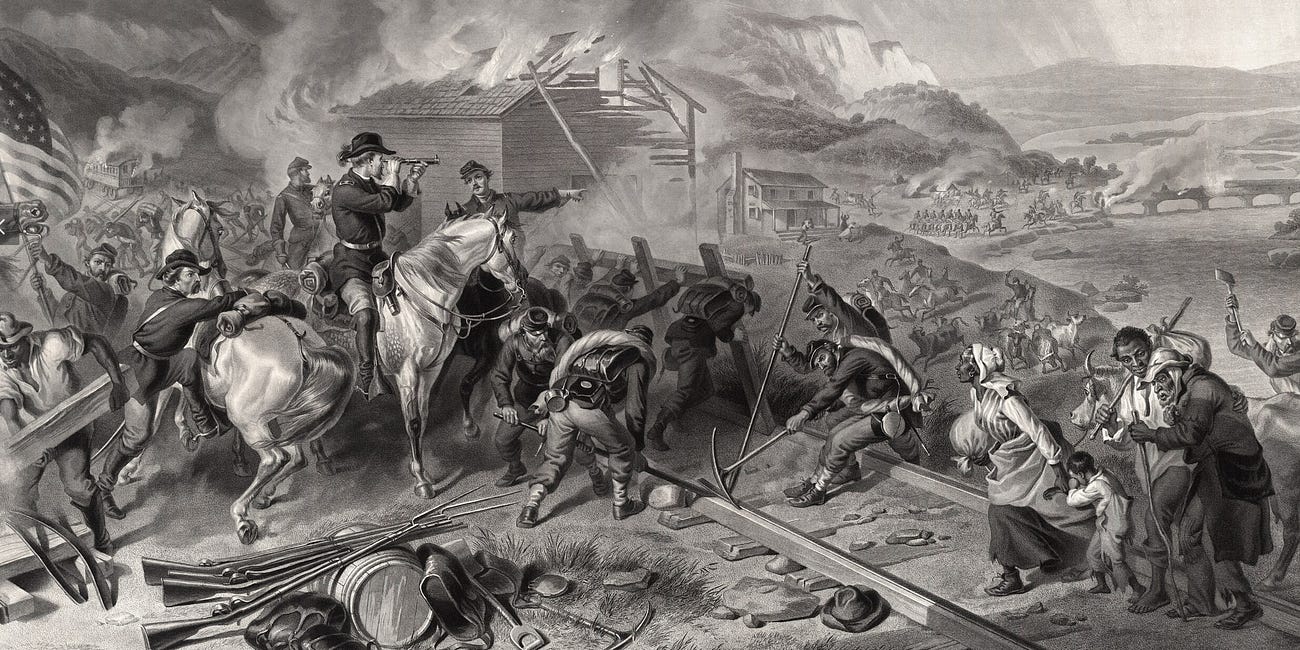

I was reminded of this as I was getting ready to interview Bennett Parten about his new book on Sherman’s March and military emancipation. Definitely check out the video and the book if you have time.

Sherman's March and Military Emancipation: A Conversation With Bennett Parten

Thanks to Dr. Bennett Parten for joining me to talk about his fantastic new book, Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation. The book offers a major reinterpretation of how the movement of Sherman’s army toward Savannah, in November 1864, resulted in the emancipation of roughly 20,000 enslaved men, women, …

There is a tension in Bennett’s book that never fully gets resolved. It offers a useful example for the point that I am trying to make.

On the one hand, Sherman’s March through Georgia liberated upwards of 20,000 enslaved men, women, and children—perhaps the largest example of military emancipation of the entire war and one that helped to bring the Confederacy to its knees and brought the nation one giant step closer to ending slavery.

General Sherman’s signing of Special Fields Order No. 15 in January 1865 opened up the possibility of land ownership for African Americans along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia.

On the other hand, the March created a refugee crisis. Hundreds of enslaved people drowned at Ebeneezer Creek, near Savannah, as the Union army removed pontoon bridges that left them exposed to pursuing Confederates. Following the fall of Savannah, Sherman moved thousands of refugees to Port Royal, South Carolina, where overcrowding and a lack of resources resulted in disease and death.

This is a tension that courses throughout Bennett’s book, but it’s one that he doesn’t attempt to resolve. We addressed this during the interview, but I wanted to draw attention to it because I think this is important to how we think about history.

Here are the final two paragraphs of the book:

This brings us back to the March and its legacy. As a matter of sheer force, Sherman’s March through Georgia made the redefinition of American freedom possible. It was as if two great forces met and converged. The army and its sixty thousand-plus marching soldiers stomped out the dying embers of a slave regime, and through the sum of their individual movements, freed people made the new idea of freedom a central consequence of the campain. One fueled the other, and in tandem, the two forces combined in Georgia to make the American Civil War not just a war between two sections or a war that would end slavery but a war that would shape the meaning of freedom for the next century or more—a war, if you will, for an American Jubilee. In the end, that—not the burning of Atlanta, Sherman’s tactics, or Sherman himself, not the grievances of the white South, and certainly not the concept of ‘total war’—is why and how we should remember the March, for, like Yorktown, Gettysburg, and Selma, Alabama, Sherman’s March to the Sea was a landmark moment in the history of American freedom.

This certainly answers to those people looking for a triumphant view of the March of freedom. But Bennett doesn’t leave it there.

At the risk of sounding inconsistent, if the March was a great watershed, it was also a missed opportunity. The freedom it produced was never conclusive. Freed refugees suffered at Port Royal; the idea of meaningful land reform ended with the war; and the winds of change that came to life in that long Savannah winter eventually died out. The March created space for people to imagine a more expansive freedom and turned the nation toward a free future, but because Sherman preferred being a flywheel to being a mainspring, because soldiers turned freed people away while on the main road, and because no one stopped to listen to the freed refugees or try to see the world as they did, this more expansive vision of freedom never got the support it needed. As a result, the Jubilee came and went with only a few of its promises fulfilled, making the months and years following the March seem at times less like a great dawning of freedom and more like an early eclipse. Despite our wishes to the contrary, this unresovled story is a legacy too. (208-90)

History is often too messy to expect to pull out a coherent story with a meaning attached that withstands close scrutiny, unless you intentionally distort it to suit your own agenda. Governments have the power to do this, but each one of us has the ability to simplify the past to serve our own personal needs.

When we do so, however, we reduce the lives of the people who came before us as merely a means to an end. We lose sight of their humanity.

Should we view Sherman’s March as a significant moment of liberation in American history? Yes. Can we also see it as part of the long history of racism, racial violence, and white supremacy? Yes.

It encompasses all of this and much more.

Our search for clarity and meaning should never come at the expense of finding a place in the complexity and confusion of the past.

Another excellent post. We want history to give us tidy knots, when in reality, it too often gives us messy packages we have to sift through to find true meaning. This is important no matter what age you study, but especially for the Civil War—and especially today.

Kevin, I really appreciate this piece because it shares the essence of the book, which showcases the very human complication of living through incredible change while trying to do our best to maintain integrity. Freedom is still a dream for so many in this world, even with all of the understandings we have from careful historical work and widespread literacy and instantaneous communications. The March and reckoning of the Army with the refugees are a milestone in the history of human freedom that we all should know. Thank you for this and for the interview with Mr. Parten.