Fighting for Union: From the Fields of Gettysburg to the Streets of Minneapolis

Over the past few weeks the nation has been focused on Minnesota. The killings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti in Minneapolis by federal agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have rallied people from around the country and the world.

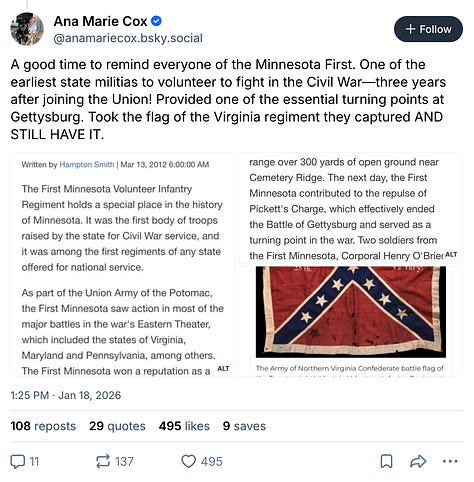

During this time I’ve seen numerous reference on social media to the fact that the state of Minnesota continues to possess a Confederate battle flag from a Virginia regiment as a symbol of its resolve.

How did it come into possession of such a flag and why does it continue to refuse to return it to Virginia?

Minnesota came into possession of a Confederate flag through the same Civil War–era practice that brought such artifacts to several Union states: the capture of enemy colors on the battlefield by Union soldiers and their preservation as evidence of service and victory. In Minnesota’s case, the flag is closely tied to one of the most storied moments in the state’s military history, namely the performance of the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment at the Battle of Gettysburg.

During the Civil War, flags were central to military life. They served as rallying points amid the chaos of battle and as symbols of a regiment’s identity and honor. Because of this, capturing an opposing army’s flag was considered a notable achievement. Union soldiers who seized Confederate colors were often officially credited for the act, and the flags themselves were treated as important trophies of war. Rather than remaining in private hands, these captured flags were typically sent to state governments for safekeeping.

Late in the afternoon of July 2, 1863, the 1st Minnesota faced an advancing Confederate brigade that threatened to break the Union line along Cemetery Ridge, the regiment was ordered to charge despite being vastly outnumbered.

Writing decades later, Lieutenant William Lochren recalled that, “Every man realized in an instant what that order meant—death or wounds to us all.” When the regiment advanced, he continued, “No hesitation, no stopping to fire, though the men fell fast at every stride before the concentrated fire of the whole Confederate force… ‘Charge!’ shouted [Colonel] Colvill as we neared the first line, and with leveled bayonets, at full speed, we rushed upon it.”

The result was catastrophic losses—over eighty percent of the regiment became casualties—but the charge bought critical time for Union reinforcements to be deployed.

The following day, two companies from the regiment helped to repulse the final Confederate assault at the center of the Union line along Cemetery Ridge. During what later became known as “Pickett’s Charge” the soldiers of the 1st Minnesota captured the battle flag of the 28th Virginia Infantry. The flag was later sent back to Minnesota as a testament to the regiment’s sacrifice and valor.

After the war, the captured Confederate flag was placed under the care of the state and eventually housed with the state’s historical and military collections at the Minnesota Historical Society. Like similar artifacts in other Union states, it was preserved not as an object of admiration for the Confederacy, but as a record of Minnesota’s contribution to the Union cause and the extreme cost paid by its soldiers. The flag became a tangible link to Gettysburg and to one of the most famous acts of bravery of any regiment to serve in the Army of the Potomac.

During a discussion about whether to return captured Confederate flags at a national meeting of the Grand Army of the Republic, in 1898 one veteran reportedly said of the notion: “When the men of the Grand Army of the Republic who have lost arms and legs have re-grown their arms and legs, then will be the time to return those flags.”

In the years since, the flag has occasionally been the subject of controversy, particularly when requests have been made for its return to Virginia. Minnesota has consistently maintained that the flag is a lawful war capture and an integral part of the state’s historical record.

When asked by members of the Virginia General Assembly in 2000 to return the flag, Minnesota’s then-governor Jesse Ventura responded bluntly: “Absolutely not. Why? I mean, we won.” And in response to a 2013 request from the Governor of Virginia to loan or return the flag for the 150th anniversary of Gettysburg, Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton’s office declined and explained the rationale:

“It was taken in a battle with the cost of the blood of all these Minnesotans. It would be a sacrilege to return it to them. It’s something that was earned through the incredible courage and valor [of] men who gave their lives and risked their lives to obtain it. And as far as I’m concerned it is a closed subject.”

I don’t know if the flag is currently on display. If not, now would certainly be a good time to remind the nation of the sacrifices that ordinary Americans have made to preserve our democracy from the fields of Gettysburg to the streets of Minneapolis.

As a Virginian and recovering lost-causer, I say to Minnesota - KEEP THAT FLAG!!! I’m going to email Governor Walz right now, attach Kevin’s excellent article, and beseech the Governor to bring out the flag for the encouragement of his state in their current struggle.

The First Minnesota had a lot of immigrants from Germany, Ireland, and Scandinavia. Proud that Minnesotans are honoring their immigrant ancestors by standing up to ICE.