I am thrilled to share my first op-ed in the The Boston Globe concerning the question of whether the name of Faneuil Hall should be changed. You can read it at the Globe or a slightly longer version here for those of you who don’t have access. This is an attempt to explore all our options when it comes to questions of public commemoration.

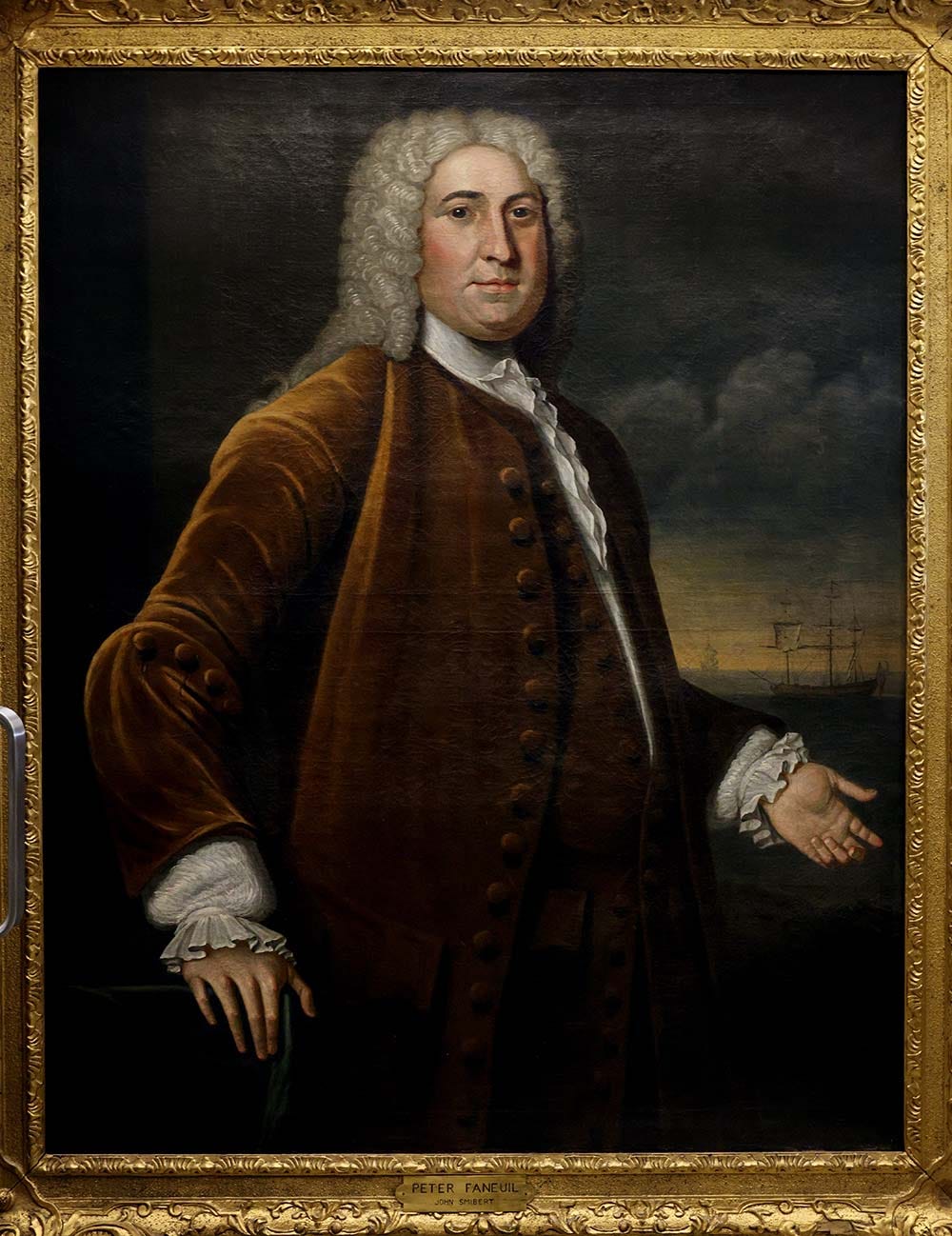

What’s in a name? For a growing chorus of activists in Boston, the name of Faneuil Hall is synonymous with the city’s history of slavery and specifically Peter Faneuil, who made a fortune by trafficking enslaved individuals and trading goods produced by enslaved labor. Much of Boston’s wealth in the 18th century was made possible by enslaved labor and the buying and selling of Black bodies.

The New Democracy Coalition has called for the city to change the name of Peter Faneuil Hall, and the Boston City Council added its voice to the debate last month by voting 10 to 3 to rename Faneuil Hall. The decision ultimately rests with the city’s Public Facilities Commission.

But changing the name cannot be our sole focus. Faneuil’s connection to this iconic building represents a small chapter in an otherwise rich history that Black Bostonians have struggled to shape over the course of the last two centuries.

The push to remake our local monument landscapes, as well as the renaming of buildings, roads, and parks, is a reminder that how we choose to remember and commemorate the past is always evolving. Communities expect that these spaces and honorific names reflect our shared values and a shared past that we can all take pride in, but we should approach the questions of removing and renaming with care, with a commitment to highlighting history that may have long been hidden and which has the potential to bring the community together.

In the years leading to the Civil War, Black and white Bostonians rallied inside Faneuil Hall to call for the end of slavery and to support civil rights. Local Black leaders such as William Wells Brown, Maria Stewart, Lewis Hayden, William Cooper Nell, and Charles Lenox Remond, as well as national leaders such as Frederick Douglass, routinely took to the stage to speak out and call for change.

Black fraternal organizations knew that Faneuil Hall was the site of key public debates leading to independence from Great Britain in 1776. They appreciated that their petitions to the Board of Alderman to use the public facility to rally for a number of causes would place them in the same space where Sam Adams and George Washington had once spoken. The voices of Black men and women filled Faneuil Hall and in doing so took their place alongside and laid claim to this legacy of the Revolution.

In 1842 a gathering of Black and white abolitionists gathered inside Faneuil Hall to issue a public statement calling for the “immediate abolition of Slavery in the District of Columbia.” Among the resolutions included the demand, “That Massachusetts must wash her hands of all participation in the enslavement of any portion of the human race, in this or any other country.”

In addition to calling for the end of slavery, Black activists demanded that Boston end its practice of segregation in its public schools and the city’s public transportation. In the wake of the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Black Bostonians rallied inside Faneuil Hall to organize resistance against the federal government’s efforts to recapture escaped slaves, who were being harbored in homes and churches along the north slope of Beacon Hill and elsewhere throughout the city.

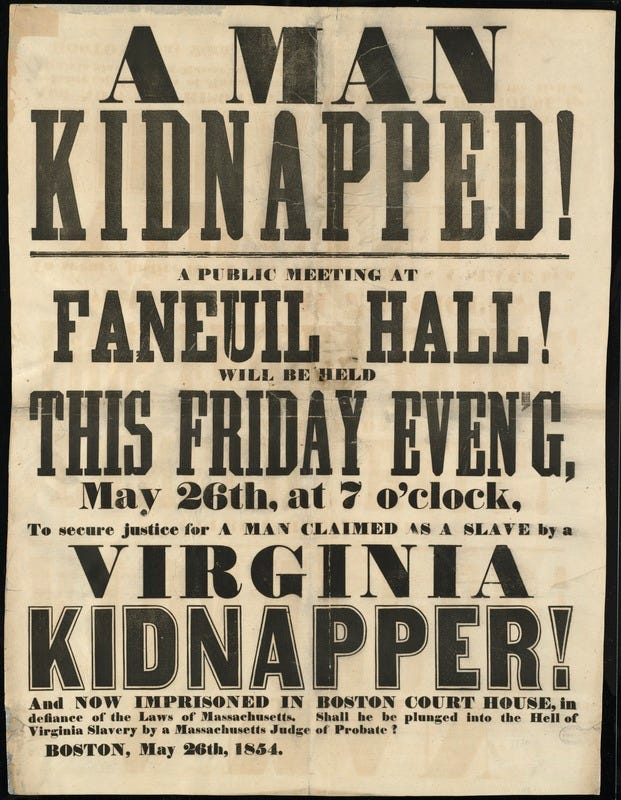

In May 1854 a broadside announced a meeting to discuss the situation surrounding the fugitive slave Anthony Burns, who was imprisoned in a Boston court house and scheduled to be returned to his enslaver in Virginia.

In the 1850s, William Christopher Nell utilized the hall to rally the Black community around the continued defense of fugitive slaves by evoking the legacy of Crispus Attucks, shot by British soldiers during what became known as The Boston Massacre and remembered as the first Black martyr of the American Revolution.

In 1888, following numerous speeches inside Faneuil Hall, a large procession made its way to the Boston Common to dedicate a new monument honoring Crispus Attucks.

By the turn of the 20th century, Faneuil Hall played host to organizations calling for increased access to the polls, the right to run for office, the end of lynching in the Jim Crow South, and to protest the dismantling of Black rights across the nation.

On December 15, 1955, thousands of Black and white activists gathered as part of the “Greater Boston Civil Rights Rally” inside Faneuil Hall to call on the federal government to provide “funds for education, housing, and welfare”; “Make lynching…a federal crime;” “Wipe out discriminatory interference with the right to register to vote in…elections”; and “Establish a permanent Federal Commission on Civil Rights.”

These activists followed in a long line of Black Bostonians, who had long before appropriated Faneuil Hall to advance their own civil rights agendas, often in the face of a violent backlash. Every time a Black man or woman walked through the doors of Faneuil Hall a statement was made that history could be overcome and that radical change was possible.

Rather than place our focus and direct our resources solely on changing the name of Faneuil Hall, tour guides, educators, and public historians need to recommit themselves to telling these stories inside and around the building with the name that generations of Black activists and reformers recognized.

One could argue that acknowledging this larger story of Black civil rights could just as easily be done, in addition to changing the name of Faneuil Hall as a sign of racial progress. I am sympathetic to this view, but I also worry that something important will have been lost. Changing the name would obscure every act of defiance that activists engaged in when they stepped foot into a building named in honor of a slave trader and appropriated the space to advance the cause of racial justice.

In doing so, they altered the very identity of the building.

For the city’s residents and the thousands of tourists who visit Faneuil Hall each year, maintaining the name should be done as a reminder of the courage of these Black activists and, more importantly, as a reminder of the radical change that has taken place in Boston.

I applaud the recent efforts to highlight Peter Faneuil’s complicity in the slave trade and the broader history of slavery in the city, but Black Bostonians left their indelible mark inside the hallowed halls of Faneuil Hall long ago and in doing so irrevocably altered its history and identity for the rest of us to learn from and be inspired by.

Kudos on your achievement! I am especially interested in this topic!

As an ex-DC-MDer, ex-federal civil rights investigator (presently a Californian, retired into CW study) I am pleased to learn this liberation-oriented history of Faneuil Hall from Kevin. Retaining its name would track with my personal yardstick for retaining or erasing names of historic personages and places: did it have a record or history of promoting enslavement, or, is there a broader history or pattern outweighing its civil-wrongs record?

Thus, enslavers Washington and Jefferson contributed more to USA development than even being major enslavers. A character like Andrew Jackson gains small credit for adopting Lyncoya, an infant Native war orphan, VS his egregious crimes against Native Peoples.

This KL post gives me the insight to complete a circuit on his recent posting about Col Robert Shaw's condescension and racism. I can easily understand how African Americans internalized their behavior with self-protecting genuflections for three and four centuries.

My late dad's incarceration in Manzanar was marked by nearly getting shot by Army MPs on a watch tower, when he strolled up to the barbed wire "Dead Line". Up to a dozen Japanese American inmates were murdered this way, because they didn't understand English, nor know the sounds of a round being chambered. (Dad had been drafted by the Japanese Army in the 1930s and was trained as a sub-machine gunner, so he knew the sound of small arms!)

Despite getting almost murdered, Dad was intensely patriotic to the USA. When a recruiting team from the 100th RCT came to Manzanar I think Dad was the only Nisei to show interest. Attempting to enlist (a recent tuberculosis survivor, he was 4-F) attracted notice of the administrators (Manzanar was riven between "loyal Americans" and dissident gangs who assaulted them) but soon had to flee to the Arkansas camps). They asked his help in tasks requiring bilingual skills.

Dad's camp files show their paternalist appreciation. His loyalty report sang his praises, but referred to him as "a fine boy". Dad was nearly 30! Soon after entering the camps in Arkansas, he won his breakthru job: a de facto social worker helping families wrecked by deportations, separations, etc.

In the 1950s, he counseled me to keep my head down, mouth shut, and work hard. That was the Japanese American way of not getting murdered-- for nearly a century. My parents kept a lifelong association with the camp administrator who gave him his break. We socialized with that family several times a year, plus on every Thanksgiving. My research found this friend was the civil servant who hired him for social work.

So, reflecting on how long Japanese Americans kept their heads down and voices small, I can easily understand how African Americans ingrained their society with self-protecting behaviors for three and four centuries. How an elderly freedman speaking to a Union colonel would feel like he was still looking up at two Whites, old master and new! Even if their "masters" were cruel and sold slave children like they sold lambs and calves, many of the newly-freed would reflexively continue the attitudes of regarding Whites as their fonts of affection.

The flip side is exemplified by Tubman (in my lifetime, by my Mom and my wife, who worked 25 years for Nancy Pelosi as her immigrant and refugee specialist), who bided her time to take the opportunities to regain or help others gain stolen opportunities.

Becoming liberated after being one-down for a long time has its own adjustments and strains.

(PS: Friday morning my wife and I attended an APEC breakfast here in San Francisco, hosted by the Speaker Emerita. --Paul looks great, BTW! -- There was a strong vibe among the MCs and diplomats that American Dems can keep the USA strong with unified action!

(Nancy is clearly happy no longer burdened being Speaker. This was also the day after a federal jury threw the book at DePape for bludgeoning Paul. The d'Alesandro-Pelosi family "knows (their) power" and America is clearly better for it. Among the Asian American MCs and our As-Am activist friends attending, the feeling of being one-down was clearly in the past, and after the Emerita's example, our political problems were simply tasks to work through with the help of allies.)

(Final PS, on Faneuil Hall: in 1980 I undertook a series of attempts to get served Indian Pudding at the notorious but beloved Durgin Park restaurant there. The meals were fine but for silly reasons, this dessert was unattainable. I doubt I will find an appropriate excuse in this distinguished forum to tell of it!)