Our nation’s capital will soon add another statue of Abraham Lincoln to its commemorative landscape. It will be located in the historic Shaw Neighborhood along the U Street corridor. This historic Black neighborhood, named in honor of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, has its roots in the Civil War, when thousands of enslaved men, women, and children flocked to the city for shelter and freedom. The military established Camp Barker in this neighborhood early in the war, a contraband camp that was eventually moved to the grounds of Arlington National Cemetery.

Howard University became the intellectual and cultural center of the community in the decades after the war. Education remained a priority for formerly enslaved people and especially their children. The neighborhood thrived well into the twentieth century.

In 1998 the African American Civil War Memorial was dedicated on the corner of Vermont Avenue, 10th St and U Street NW, in the heart of the Shaw neighborhood. The memorial was the work of local city councilman Frank Smith, who also founded the African American Civil War Museum, now located across the street from the memorial.

Last week I interpreted the memorial for a group of teachers as part of a professional development workshop organized by Ford’s Theatre. Our focus for the week was the history and memory of the Civil War era. We were hoping to visit the museum, but unfortunately it is still closed. The museum is in the process of moving to a former schoolhouse located directly across the street from the memorial.

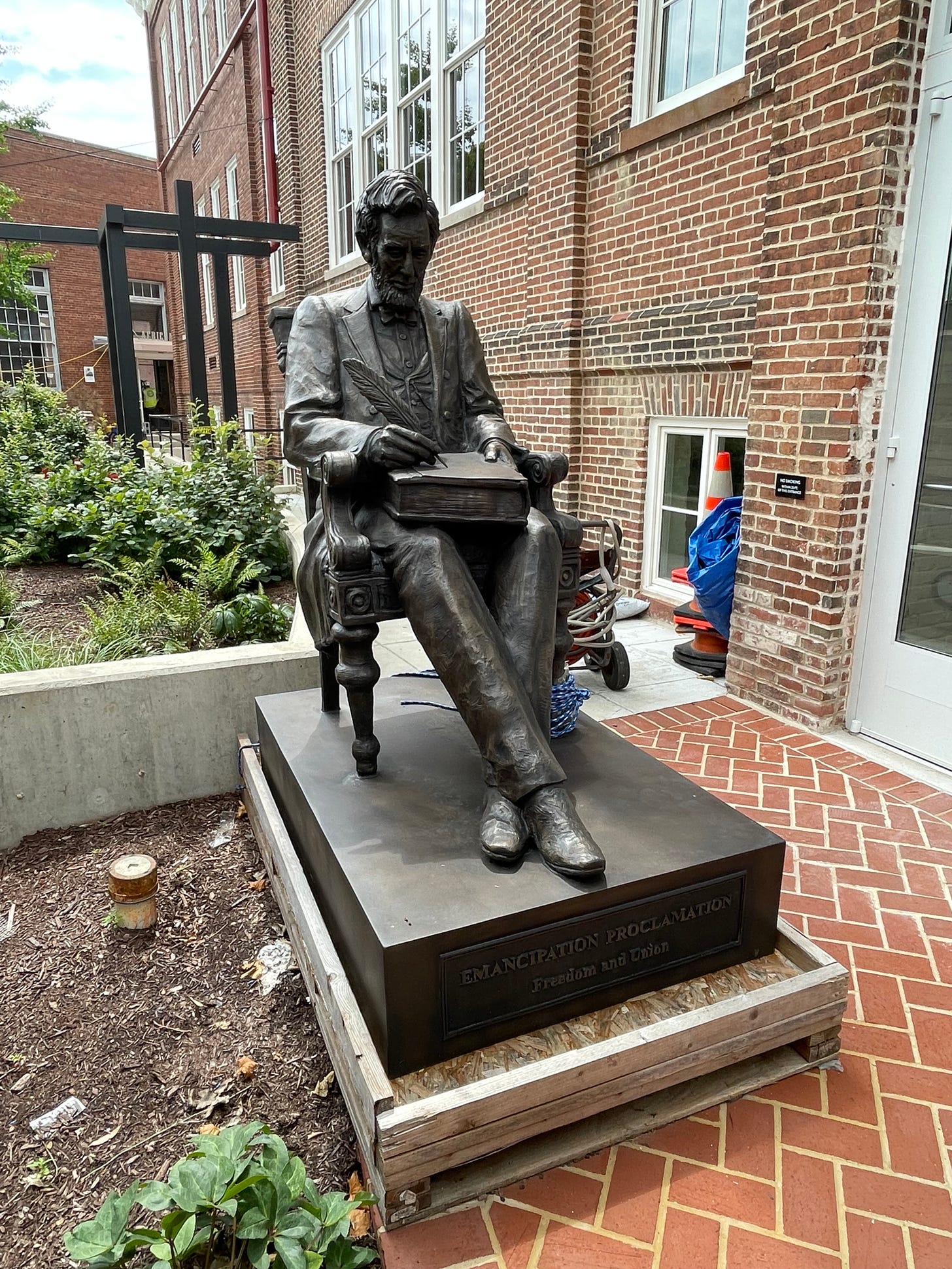

This is going to be a wonderful new facility for the museum and an important cultural asset for the entire community. I was somewhat surprised to learn that the museum plans on dedicating a new statue honoring Abraham Lincoln and his role in emancipation to be placed on the steps of the new museum—a former schoolhouse (1887) that honors Archibald Grimke (1934). I managed to snap a shot of the new statue, which is on site in an alley between the the old museum and the new building.

The proximity of the new statue and the African American Civil War Memorial will certainly offer opportunities to interpret them in conversation with one another, but I want to focus a bit on Archibald Grimke as a way to explain my ambivalence about the decision to add another statue of Lincoln in the city.

Born enslaved in South Carolina in 1848, Grimke was the nephew of noted abolitionists Angelina Grimke Weld and Sarah Grimke. He graduated from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and Harvard Law School, after which he practiced law, edited a newspaper, served as a diplomat, and played an active role in the civil rights movement. He went on to found the NAACP and served as president of the D.C. branch of the organization. [For a fascinating new study of the Grimke family, I highly recommend Kerri K. Greenidge’s new book, The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family (Liveright, 2022)]

The excerpts that follow come from an essay that Grimke published in 1900 in Howard’s American Magazine.

It seems to me that it is high time for colored Americans to look at Abraham Lincoln from their own standpoint, instead of from that of their white fellow-citizens. We have surely a point of view equally with them for the study of this great man’s public life, wherin it touched and influenced our history. Then why are we invariably found in their place on this subject, as on kindred ones, and not in our own? Are we never to find ourselves and our real thought on men and things in this country, and after finding them are we to deny to them expression, for fear of giving offence? Are we to be forever a trite echo, an insignificant ‘me too’ to the white race in America on all sorts of question, even on those which concern peculiarly and vitally our past, present and future relations to them? Is it due to some congenial race weakness, or to environment, to the slave blood which is still abundant in our veins, that we rate instinctively and unconsciously whatever appertains to them as better than the corresponding thing which appertains to ourselves, and count always what we receive from them, although vastly inferior in quantity and quality, an immense superior to that which we give in return? Are we never to acquire a sense of proportion and independence of judgment, but must go on with our own brains befuddled with the white man’s prodigiously magnified opinion of himself and achievements? I hope not; I do most devoutly pray not. For if we are ever to occupy a position in America other than that of mere dependents and servile imitators of the whites, we must emancipate ourselves from this species of slavery, as from all others. And the sooner a beginning is made in this regard the better. With whom then can we more appropriately begin this work of intellectual emancipation than with Abraham Lincoln, the emancipator?

…. Was Abraham Lincoln a great American? Yes, certainly. Was he one of the greatest of American statesmen? Yes, assuredly. Was he a great philanthropist? No. Was he a great friend of human liberty and the Negro, like Garrison, Sumner, and Phillips? No, a thousand and one times, no! For the sake of truth let us answer ‘yes’ every time where ‘yes’ agrees with the facts of history and ‘no’ where simple honesty forbids and other reply. And then let us be done, once and forever, with all this literary twaddle and glamour, fiction and myth-making, which pass unchallenged for facts in the wonder-yarns which white men spin of themselves, their deeds and demigods.

The theme of self-determinations runs throughout this speech. Grimke wanted African Americans to move beyond the narrow view of Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator” and to acknowledge the extent to which he had resisted emancipation as a wartime measure. He was correct in acknowledging that the preservation of the Union was Lincoln’s priority.

There are aspects of this speech that remind me of Frederick Douglass’s address at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in D.C. on April 14, 1876. In that speech Douglass also attempted to place Lincoln’s achievements in broader historical context and to implore his overwhelmingly Black audience to recognize that they were but his “stepchildren.”

I can’t help but wonder what Archibald Grimke would think of this new addition to D.C.’s monument landscape, especially given its eventual home in the Shaw neighborhood. I think he would say that this is a missed opportunity to shine the light on any number of African American leaders or historic moments in the story of emancipation and Black freedom.

Why not honor someone like Carter G. Woodson, Paul Dunbar, Alain Locke or even Grimke, to name just a few.

Don’t get me wrong. I have never called for the removal of a Lincoln statue. There is much that I admire about our sixteenth president and much that is worth commemorating and remembering in our public spaces, but Washington already includes three monuments/statues in his honor. It boasts the earliest statue of Lincoln dedicated in 1868 in what is now Judiciary Square, the more problematic Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Square, dedicated in 1876, and, of course, the Lincoln Memorial (1922).

All three are provocative in their own way, but this newest one falls flat. It is simply Lincoln sitting signing what appears to be a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation on top of a book. The statue provokes little reflection. In fact, my first impression is that it does little more than reinforce the old “great emancipator” narrative—the very thing that Grimke warned his readers against.

Overall, it’s hard to see what, if anything, adding another statue of Lincoln does for the city and especially for the historic Shaw neighborhood.

No.

Was Lincoln a philanthropist and "(a) great friend of human liberty and the Negro (etc.)"? In contrast with Grimke, I say yes, yes, and yes!

Yes, I speak with eight-score years of hindsight. Plus, my standpoint is like Grimke's and thousands of freed persons. While savoring their historic freedom, they were begrudged it by many Whites who saw them as the undeserved reason for their war sorrows -- loved ones' deaths and maiming in battles, and other losses by vicissitudes of war.

Likewise, growing up after World War 2, I tasted the same hatred, living in a nation that overwhelmingly saw in me and my family the personification of a recent enemy.

Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was generously bought with the nation's worst battlefield of blood atop two years of bleeding before Antietam. The final Proclamation presaged the grudging permission of the nation to allow the African American man to shed his blood to help purchase his own liberty. Lincoln did as much as he could, as quickly, as the northern fraction of the nation allowed...and Grimke knew what reward Lincoln had received.

In December 1941 my eldest uncle enlisted to prove he was a loyal American (even as the eldest son, he was exempt from service). He was "allowed" to be trained as a medic (other Nisei were denied enlistment, kicked out, or put into service companies) until 1943, when the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team was authorized, modeled after the U.S. Colored Troops. Like many of the USCT's, his younger brother volunteered out of the Jerome, Arkansas, concentration camp (our version of a plantation). Yeah, 80 years later and the army still didn't trust non-Whites born in the USA. (Tom served in France and was awarded the Purple Heart; Goro entered the Military Intelligence Service, just in time to participate in the Battle for Manila. Both were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.)

(b) I compare the new Lincoln sculpture to the Memorial of marble in Washington, where I grew up, and the bronze statue in front of City Hall, San Francisco, where I live now (it's been there for 97 years, twice as long as moi). All show him seated and thoughtful. Artistically, it compares with the US Treasury rolling out another sheet of five dollar bills.

I concur that if there's to be another statue of Lincoln, this one's contribution is minimal. Couldn't an original theme be commemorated? Perhaps, the Lincolns visiting a contraband camp, appreciating each other.

Like Cato the Elder, tho, I would go out of my way to view this Lincoln statue in DC, than visit a representation of REL, anywhere, unless it was to witness its being beaten into plowshares.