I didn’t anticipate hitting the computer first thing in the morning to write another post about Gettysburg. Two is enough on any given week, including the week of the anniversary of the battle, but an op-ed published today in The New York Times demands a response.

Author Simon Barnicle visited the park in April and walked away clearly disturbed by what he saw:

But for all the learning one can do at Gettysburg, there is a remarkable dearth of education. The National Park Service has in recent years made attempts to better contextualize the park. In 2008, a new visitor center opened that includes a small privately owned and operated Civil War museum for an extra fee. More recently, the park has added a couple of interpretive markers near Confederate monuments, which acknowledge the extent to which they sidestep the root causes of the war. These efforts are halfhearted at best. The main attraction remains the experience of visiting the battlefield itself — absorbing battle facts while surrounded by tributes honoring both sides.

The park is notably lacking in historical context and moral valence. Why was the war fought? What did Gettysburg mean for the United States? Was slavery good or bad? The answers to these questions may seem so obvious that they don’t require explanation, but the décor at the park and in the town of Gettysburg suggests otherwise.

In gift shops lining the streets downtown, I saw Confederate flags emblazoned on hoodies, koozies, car tire covers and underwear. T-shirts for sale featured slogans like “If at first you don’t secede, try, try again,” and “Descendant of a Confederate Civil War soldier.” There were Confederate beanies, ball caps, cowboy hats and more.

Even the official park store is in on the fun. For just $29, you can get your own Gettysburg Cannon Snow Globe, complete with a Confederate flag mounted alongside the Union one in the center. It would be a scandal and an outrage if, at the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York, you could purchase a snow globe with an Al Qaeda flag. It shouldn’t be OK for Confederate paraphernalia.

Gettysburg is a complicated place. The park’s physical and interpretive landscape have been shaped by a number of factors beginning almost immediately following the bloody battle in July 1863. Any assessment of Gettysburg must be sensitive to this history. Historical context and change over time matter.

Unfortunately, this op-ed reflects the public’s recent obsession with the Lost Cause. There is no question that it looms large at Gettysburg, most notably in the large Confederate monuments located along Seminary Ridge. Interestingly, the author makes no mention of these monuments.

The quantity of Confederate imagery at Gettysburg is a testament to the enduring power of Lost Cause ideology — the revisionist, pseudohistorical thesis dreamed up by defeated Southerners who maintained that the Civil War was not primarily about slavery and that the antebellum South was unfairly maligned by opportunistic Northerners.

The park’s hyperfixation on battle details and hand-wavy approach to everything else are hallmarks of the Lost Cause. If tourists spend all their time focused on the who and the what of Gettysburg — the generals, the regiments and the tactical decisions — they might forget to ponder the why.

To reduce the park’s interpretation to the Lost Cause misses the important work that has gone into aligning the stories told with more recent scholarship on the Civil War era. The author should have spent much more time in the visitor center. The exhibit on the battle and the war is one of the best around.

The exhibit, which is organized into 12 sections beginning with the causes of the war and ending with battlefield preservation. Each room has a theme which is connected to a snippet from the “Gettysburg Address”. So, for instance, the room on the campaign into Pennsylvania is titled, “Testing whether that nation can long endure” and the room on the period between 1863-1865 is titled, “The great task remaining before us.” Beyond the history of the battle, the rooms also discuss the civilian experience of both black and white residents of Gettysburg as well as the aftermath of battle and how Gettysburg has been remembered and commemorated over the years.

Both the exhibit and the film make it clear that slavery was the cause of the war and the abolition of slavery and preservation of the Union were its most important results.

Visitors to the park also have the opportunity to walk the battlefield with NPS rangers and historians. The focus of these walks and presentations introduce visitors to a wide range of subjects beyond the movement of troops and fighting. Many park rangers are now graduates of programs at colleges like Gettysburg College, University of Virginia, Virginia Tech, Shepherd College and elsewhere that offer students internship opportunities at Civil War sites. Their classroom and on-site work is helping to push battlefield interpretation in new and exciting directions.

As I see it, the biggest challenge at Gettysburg is narrowing the gap between the experience of visitors, who begin at the visitor center and those who simply park and walk the battlefield on their own. This is a challenge at any number of historic sites.

It’s the lack of interpretation on the battlefield—a distinction that is obscured in Barnicle’s piece—that exposes visitors not as much to the Lost Cause, as he suggests, but to that other category of Civil War memory: reconciliation.

Visitors get caught up in the ebb and flow of battle without reflecting on why there was a battle at all, how it fit into the broader history of the war, and its legacy. The experiences of the rank-and-file are reduced to three days of battle as if the color of their uniforms were insignificant and the side on which they fought didn’t matter.

Soldiers are all equally brave when viewing the battle through the lens of reconciliation. No one shirked their duty or behaved cowardly. The pristine landscape itself shapes the viewer’s experience by smoothing over the horrors of battle.

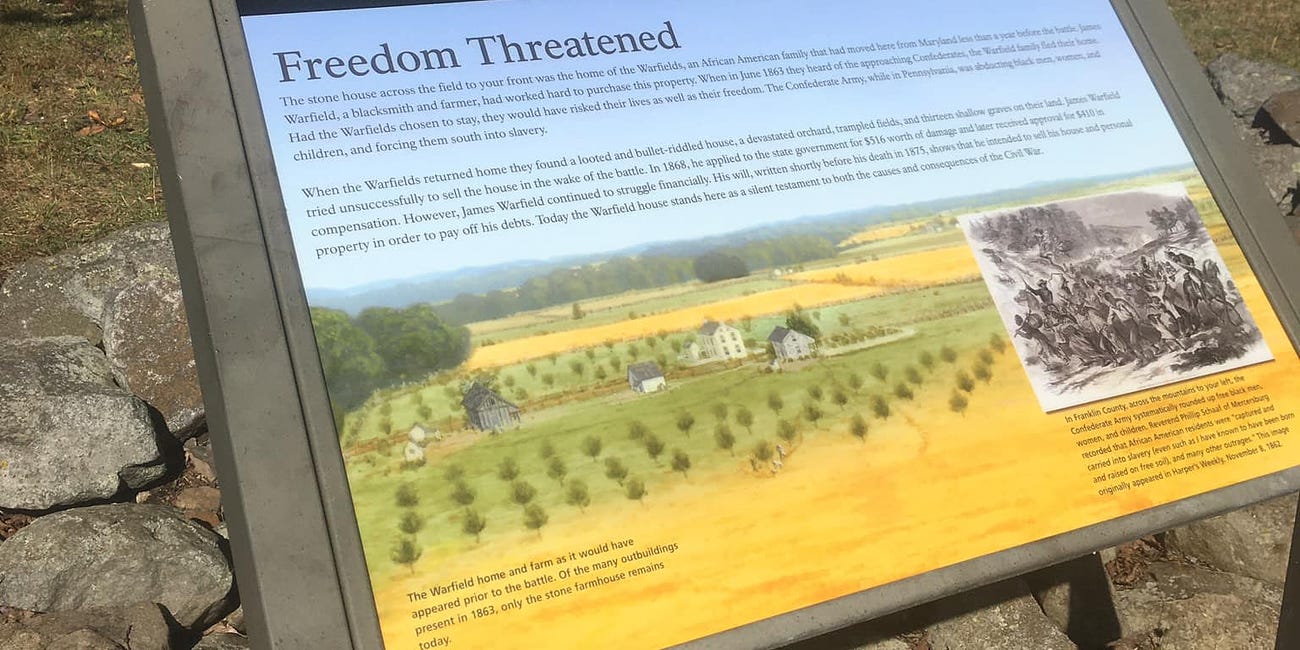

New interpretive markers have gone up around the battlefield, the content of which the author ignores, but any NPS employee at Gettysburg will readily admit that it is far from sufficient.

Having finished reading Barnicle’s op-ed I have the feeling that he went to Gettysburg looking for the Lost Cause. Like I said, you can find it, but if visitors spend their time wisely they will experience a much more nuanced and exciting place.

Ultimately, if you want to see even more change at battlefields like Gettysburg, call your local representatives. More importantly, vote for people who believe that our historic sites are worth saving and interpreting for all Americans.

Thanks for reading. I hope you and your family have a safe and happy Fourth of July.

Excellent rebuttal. If anything the Reconciliation narrative has a stronger hold on the battlefield than does the Lost Cause. That said, the NPS is doing what it can. Is the overall vibe there in terms of narrative dated? Yes, to those of us on the cutting edge of interpretation. For the public at large, some of what they’ll see will challenge what they’ve always known.

This site is still a work in progress, and that’s not just rehabbing the physical space like Little Round Top or tearing down the old Pickett’s Buffet. How this battle is interpreted continues to evolve, it’s come a long way and it has miles to go. The NPS is trying to do something with public tax dollars without alienating the people who pay for their existence. That is difficult. I think they’re doing as good a job as they can.

Had the author looked harder in the battlefield gift shop, he would’ve found excellent books on the causes and consequences of the war in the same place he found the snow globe.

Thank you for taking time to answer the NYT op-ed, I hope someone (you?) submits it as an excellent rebuttal.

The way the Visitors Center is organized around Lincoln’s words is excellent. Well done, to whoever imagined that concept, and everyone who brought it about.