Sometimes the complete lack of historical evidence forces the historian to admit that there is nothing that can be said about a certain subject or at most that any explanation is highly speculative. More often than not, however, historians are forced into a gray area of limited or inconclusive evidence that points to a possible explanation only as a result of having spent considerable time piecing together the larger story.

I tend to think of this as exercising what you might call the brewmaster’s nose. The expert brewmaster knows when a batch of beer is just right even if the exact ingredients are unknown. It comes with time spent learning about individual ingredients and observing, smelling, and tasting how they interact with one another.

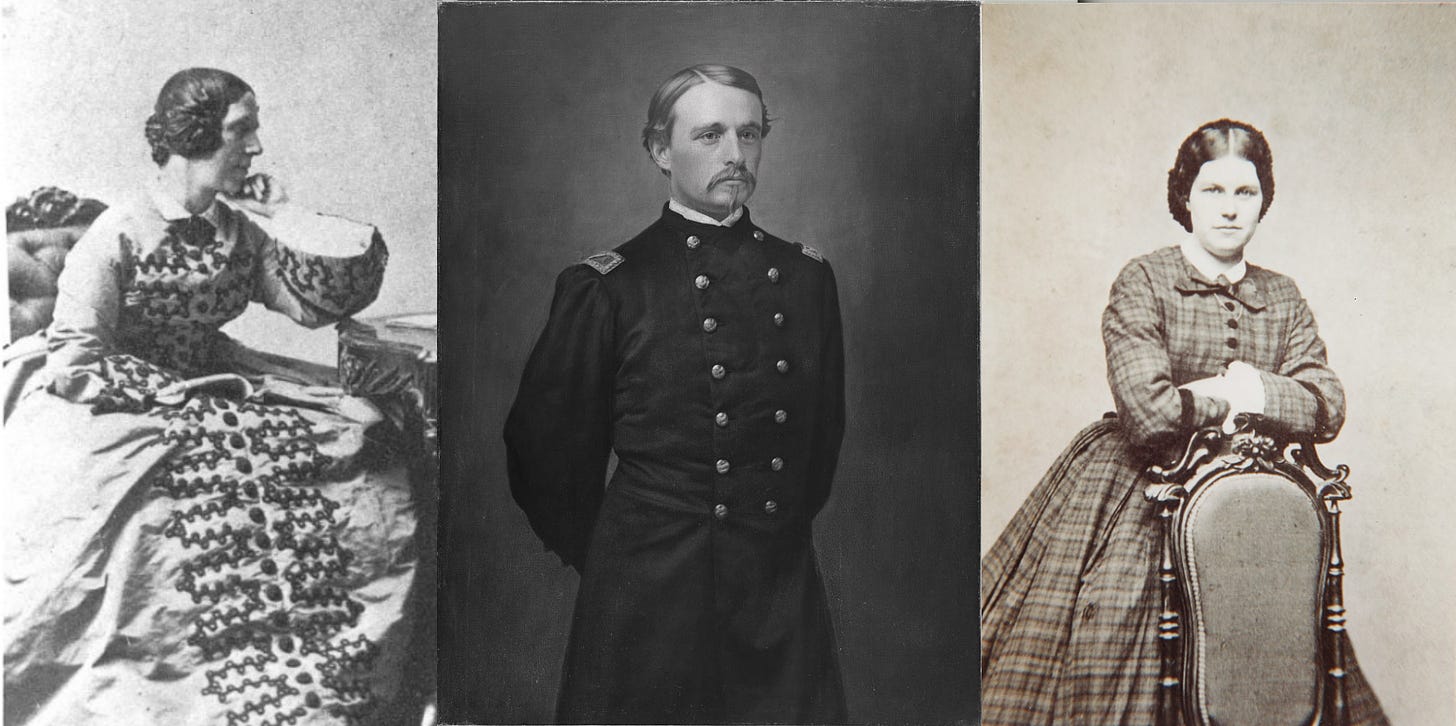

I had one of those experiences today while working on my biography of Robert Gould Shaw, specifically with a letter that he wrote to his sister Josephine (or Effie) on January 25, 1863. Robert had just returned from a ten-day furlough to visit with his fiancee, Annie Kneeland Haggerty, as well as his family in Staten Island. Robert and Annie were engaged and would be married in May 1863, just weeks before he shipped out with the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry to South Carolina.

There is some evidence to suggest that Shaw’s parents, particularly his mother Sarah, did not approve of their engagement or of Annie. There may have been some concern about Annie’s class, but this is unlikely given the extent to which the Shaw family defied Brahmin cultural norms. There is nothing that I can firmly put my finger on, but it’s something that you get a sense of the more time you spend with Shaw’s correspondence.

Here is the passage in question that I am trying to explain:

I hope you wrote or will write to Annie H. as you intended to, and that you will get well acquainted with her when she comes down to stay with Susie. Tell her to stand straight. No you needn’t say so from me. I don’t feel certain that she considers that matter entirely settled. [emphasis in the original]

Susie was another one of Robert’s sisters. In fact, she was the one who introduced her brother to Annie on the eve of the war.

This excerpt is incredibly frustrating because Shaw’s correspondence is almost always transparent. Of course, it could be the case that a reference to ‘standing straight’ is simply a reference to poor posture.

But perhaps we should interpret “stand straight” to mean ‘get a backbone’ or ‘stand up’ to something or someone with which you disagree. What I find confusing is the follow-up sentence: “I don’t feel certain that she considers that matter entirely settled.” It seems unlikely that the “matter” which Shaw is referring to here is poor posture, but again I could be entirely mistaken.

A deeper reference to internal family conflict just smells like the right explanation given the amount of time I’ve spend with Shaw’s broader correspondence related to the tension between Annie and Sarah.

Please know that I have not yet included an interpretation of this particular passage in my manuscript. I am going to sit with it for a bit longer. In the end, I may not say anything at all.

Understanding the family dynamic between Robert, Annie, and his mother on the eve of their marriage is important for a number of reasons. Shaw was already under great pressure once he accepted command of the 54th less than two weeks after he penned the above referenced letter on January 25th. As for Annie, difficulty with her future mother-in-law would have only added to her concerns about Robert’s decision to command a Black regiment and the dangers he would likely face once in the field.

Thinking carefully about this family dynamic may also help to piece together why Annie disappeared so quickly following Shaw’s death at Battery Wagner on July 18, 1863. There is something to explain here, but the evidence is scant at best. Annie never spoke in public or wrote anything about her late husband. If there was tension between the two women, it may help to explain Annie’s abrupt departure. So many questions.

This may seem inconsequential, but I am learning that every detail counts in trying to piece together the life of Robert Gould Shaw and the people he cared most about.