Did Robert Gould Shaw Have to Volunteer the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts to Prove Their Bravery?

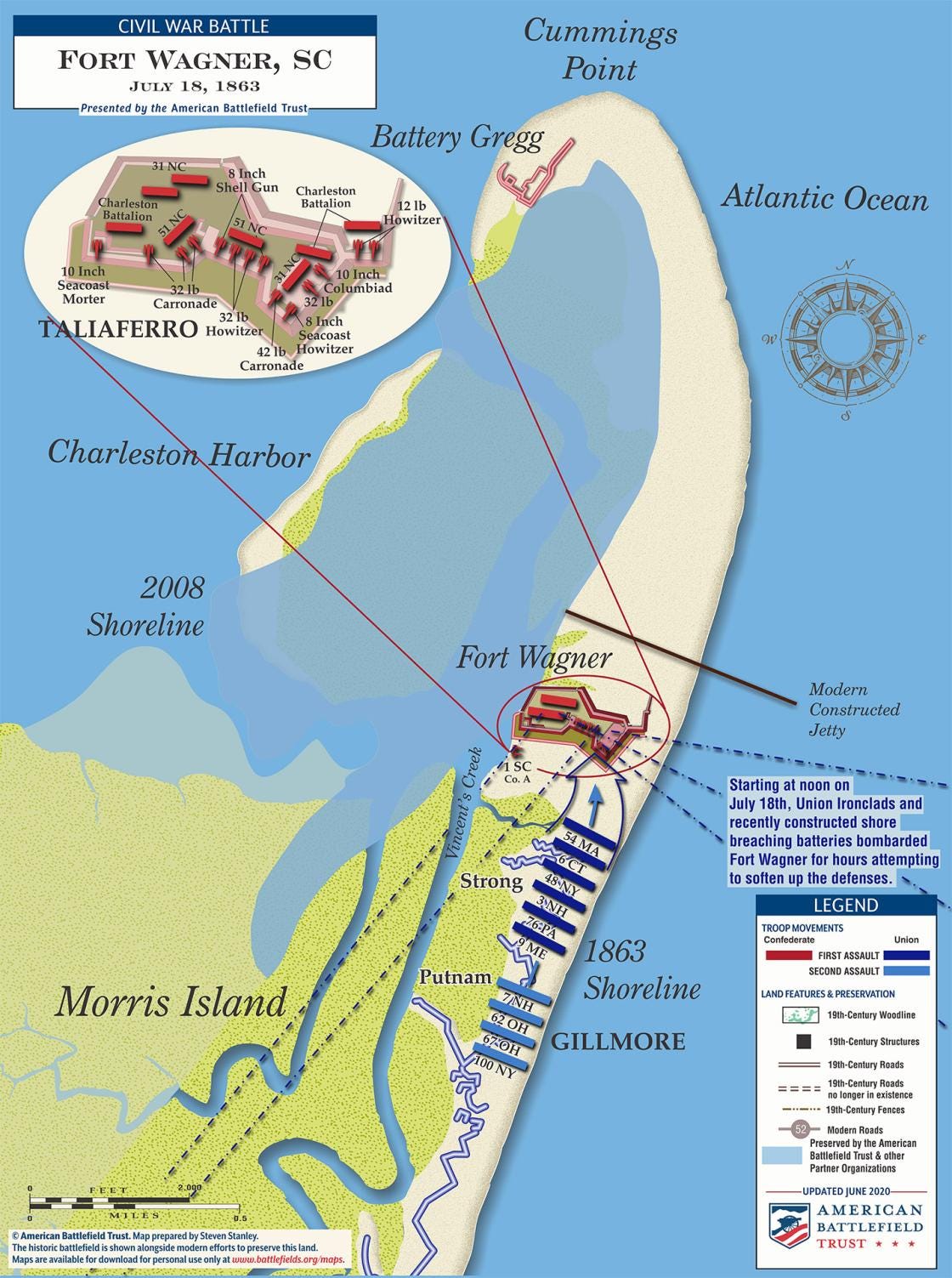

Questions linger about the assault on Fort Wagner, which took place on this day in 1863.

This is a slightly revised post that appeared in January 2024 for paid subscribers only.

Today is the 161st anniversary of the assault on Fort Wagner, led by Col. Robert Gould Shaw and the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The story has been told time and time again in history books and, of course, in the 1989 movie Glory starring Matthew Broderick as Shaw.

It’s impossible to deny Shaw’s bravery as well as the Black men under his command that day. The regiment was forced to attack a highly fortified Confederate position at dusk, along a narrow strip of land bordered on one side by the Atlantic Ocean and the marsh on the other. Even with the setting sun, there were few places to hide once the attack commenced.

As you all know, the attack failed. Roughly 40% of the regiment was counted as casualties, including Shaw himself, who was killed while scaling Wagner’s ramparts.

Of course, what makes the assault even more dramatic and memorable is the fact that Shaw volunteered his regiment to lead the assault. Who doesn’t love the penultimate scene in Glory when Shaw steps up to volunteer his regiment even after learning that the casualties were expected to be high.

In this scene, Shaw is presented as someone who is still trying to prove the worthiness of his regiment. After Brig. Gen. Strong notes the condition of the Fifty-fourth, Shaw responds: “There is more to fighting than rest, sir. There is character. Their strength of heart. You should have seen us in action two days ago. We were a sight to see.”

The engagement that Shaw was referring took place on James Island, two days earlier on July 16.

Many people, beginning with soldiers in the other regiments who took part in the action that day not only witnessed the Fifty-fourth in action, they acknowledged their fighting skills and bravery. Newspaper coverage guaranteed that much of the country would also learn about what the regiment had achieved that day on James Island.

Four companies of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts were on picket duty near Grimball’s Landing on the night of July 15. The Tenth Connecticut took up position on the regiment’s left, with its left flank anchored close to the Stono River. A swamp, however, created a dangerous gap between its right and the left flank of the Fifty-fourth. The Second South Carolina and 104th Pennsylvania took up a position on the regiment’s right on the ground of the Legare Plantation.

Confederates began probing the Union pickets in the pre-dawn hours of July 16. Scattered rifle could be heard up and down the line. As dawn neared, Confederates lobbed a few shells that landed harmlessly behind the picket line. At daylight, roughly 1,400 Confederates, supported by artillery, began their assault opposite the Tenth Connecticut, but soon spread down the line.

Captains Cabot Jackson Russell of Company F and William Simkins of Company K did their best to hold their men in place. “As their force advanced on our right,” recalled Corporal Gooding, “the boys held them in check like veterans; but of course they were falling back all the time, and fighting too.”

There were moments when Confederates thought they had finally broken through only to find that the Fifty-fourth had managed to form up again in time to fire another volley into their ranks. After holding the Confederate advance for up to an hour, the regiment finally gave way and headed back toward the rest of the division.

Though the engagement was brief and involved relatively few men, the fighting was no less intense for those involved. A mounted Confederate officer twice lunged at Captain Russell with his sword only to have his third swing deflected by the bayonet of Preston Williams and managed to shoot the determined enemy in the neck. His actions likely saved Russell’s life. Sergeant James Wilson of Company H defended himself against five Confederates with his bayonet and managed to kill four of his attackers before being overtaken and killed. The regiment lost 14 killed, 17 wounded and 12 captured. Reports of the execution of captured Black soldiers echoed through the camp.

As the remnants of the picket line took up position with the rest of the regiment, Captain Emilio noticed “some of the wounded limping along unassisted, others helped by comrades.” “One poor fellow, with his right arm shattered, still carried his musket in his left hand.” By then the rest of the division had prepared for the inevitable assault, but other than a few exploding shells and falling branches, it never materialized as Confederates realized that they would be in range of federal gunboats along the Stono River and Big Folly Creek.

The delaying action on the part of Shaw’s men afforded General Terry ample time to organize the reset of his division, but more importantly, it provided valuable minutes for the men of the Tenth Connecticut to extricate themselves from their vulnerable position. One Connecticut soldier wrote: “But for the bravery of three companies of the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth (colored), our whole regiment would have been captured. As it was, we had to double-quick in, to avoid being cut off by the rebel cavalry. They fought like heroes.”

After the battle, Shaw sent out squads of men to collect the wounded and dead on the battlefield. A few of the dead appeared to have been mutilated by Confederates, but a closer look revealed that the condition of the bodies was the result of fiddler crabs and other insects.

“You don’t know what a fortunate day this has been for me, and for us all,” Shaw proudly reported to his wife Annie. Shaw was thrilled with the performance of his men. Any question as to whether the men in the Fifty-fourth needed bayonets at their back in order to fight were dispelled once and for all. Not only had his men stood their ground, they demonstrated their bravery and skill in front of a regiment of white soldiers, who now applauded for saving them from capture or worse.

Shaw welcomed General Terry’s message in which he applauded the bravery of his men. Terry singled out the Fifty-fourth in his official report for its “steadiness and soldierly conduct” and highlighted that it had “met the brunt of the attack.”

On the evening of July 16 the Fifty-fourth was ordered out amidst a torrential thunderstorm. The next day the regiment marched up Folly Island to its northernmost point overlooking Morris Island. The men were exhausted and had nothing left to eat beyond what little rations remained. On the morning of July 18 the regiment was transported across the channel followed by another march to the forward Union positions in front of Fort Wagner.

By the time the Fifty-fourth arrived on Morris Island word had spread of the recent fighting on James Island. The rank and file had proven their bravery and skill to Shaw and their company officers. General Terry and other senior officers had congratulated Shaw and his men on their performance. Soldiers in the Tenth Connecticut also praised the men of the Fifty-fourth for protecting their vulnerable flank and preventing them from being taken prisoner.

Northern newspapers also acknowledged the bravery of the Fifty-fourth as well. Shaw was finally able to begin to move on from the humiliation of participating in and the controversy surrounding the burning of Darien, Georgia on June 11, just a few days after the regiment arrived in Beaufort, South Carolina.

All of this raises the question: What exactly did Shaw hope to gain by volunteering his regiment on July 18 that had not already been achieved on James Island two days earlier?

I ask this question because our memory of the battle tends to assume a certain inevitability. Shaw is somehow destined to sacrifice himself for the larger cause that his men represent and emancipation generally on that small sandy island guarding Charleston harbor.

Shaw knew that the previous assault on Wagner on July 10 and 11 had failed and that few steps had been taken since then to improve the changes of a successful assault beyond the continued bombardment by naval ships just offshore. More importantly, Shaw was fully aware of the condition of his regiment.

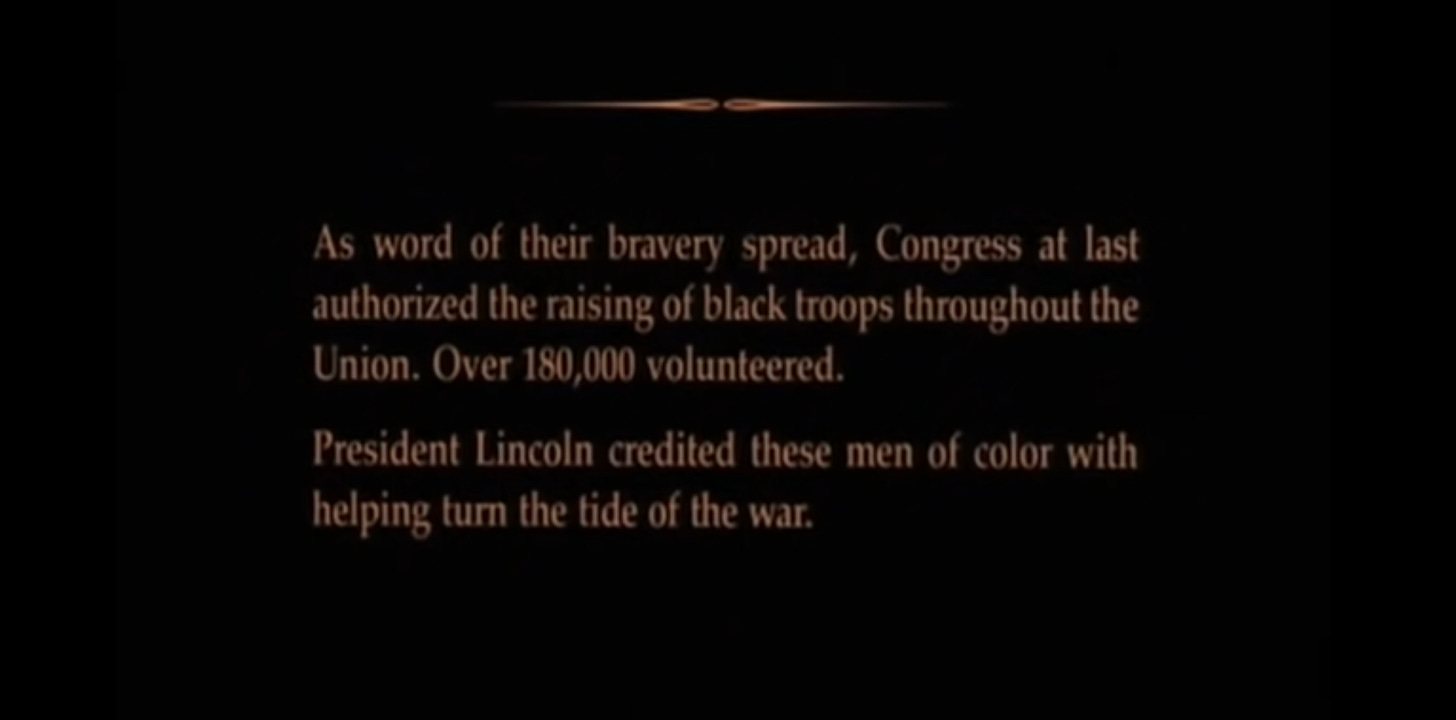

The Fifty-fourth’s failed assault on Fort Wagner is often credited with turning the tide of public sentiment in favor of the enlistment of Black soldiers. This view is reinforced in Glory just before the closing credits.

Word certainly did spread throughout northern newspapers, but as historian Glenn D. Brasher has argued, this has likely been overstated. Newspaper coverage, according to Brasher, “reveals that northerners bitterly contested the regiment’s effectiveness. Further, that dispute, and especially the treatment of the regiment’s prisoners, added fuel to the volatile question of racial equality and African American citizenship.” (p. 22)

In other words, newspaper coverage of the battle and the role of the Fifty-fourth specifically fell along political lines.

Having finished writing a biography of Shaw, I now more clearly see how the postwar efforts by members of Shaw’s family and others worked to shape the memory of the the young colonel and his Black regiment. More importantly, the focus on Shaw’s bravery and that of the Fifty-fourth helped to obscure or avoid the question of whether the assault itself was reckless and a needless waste of human life.

Let me close on this anniversary by once again making clear that Shaw’s bravery and that of the men under his command is unquestionable. Shaw did not have to volunteer to take command of the Fifty-fourth. He put his reputation and his life on the line. Shaw also did not have to volunteer his regiment to lead the assault on Fort Wagner.

But historical context always matters when studying the past, especially when it comes to stories that have long gone unquestioned and which are seared into our collective memory.

Absolutely fascinating story with much to chew on. Based on experience in Iraq, Somalia, and elsewhere, everyone in a hierarchical organization like the army must soon come to terms with being one throw of the dice away from someone else’s ill-considered notion

Pretty clear from this post that when that book comes out, it'll be gripping on more than one level.