Imagine it for a moment. Harriet Tubman, the “Moses of her People” serving Col. Robert Gould Shaw his final meal on Morris Island before leading the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts in its ill-fated charge against Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. The scene fits neatly in a narrative that places Shaw at the center of the story of emancipation.

But is the story true?

I’ve been wrestling with this and a few other stories as I bring my biography of Shaw to a close.

There are a number of sources for this story, including Kate Clifford Larson’s fabulous biography of Tubman, titled Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero. If you are looking for a biography of Tubman, this is the one to read.

Kate has been incredibly helpful in walking me through her interpretation of this particular moment and I very much appreciate her patience.

First, here is how she frames this particular moment in the biography:

Tubman had followed the regiments up the coast to their positions outside Charleston Harbor. Probably there as a nurse and cook, but perhaps even as a scout, Tubman witnessed the carnage inflicted upon the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts on July 19 at Fort Wagner. She later told an interviewer that she served Colonel Shaw his last meal. She had probably become quite familiar with Shaw and his regiment since they had arrived in Beaufort six weeks before. Frederick Douglass’s two sons, Lewis and Charles, were members of the Fifty-fourth, and Tubman no doubt knew both young men.” (p. 220)

The source for this story can be found in Earl Conrad’s biography of Tubman published in 1943. He based this, in turn, on Hildegard Hoyt Swift’s book for young adults, titled The Railroad to Freedom: A Story of the Civil War, which was published eleven years earlier. Though the book is a fictionalized account, the author consulted with two of Tubman’s nieces and other archival sources. Swift confirmed the story to Conrad in 1939, writing: “She [HT'] always stoutly maintained that she fed Col. Shaw his last meal etc. and that she was present at the time [of the assault on Fort Wagner].”

Kate acknowledges that the source for this story only appeared decades after the event in question. She rightly points out that there were few people in a position to confirm the story and, of course, Tubman herself was illiterate. I agree with Kate that Tubman also didn’t have a reason to lie about this story after the war.

It is certainly possible that Tubman served Shaw his last meal. Apparently, Tubman also noted that she served Brig. Gen. George C. Strong a meal before the assault, but he succumbed to his wounds shortly after the battle. Shaw did meet with Strong around 6:00 PM, where he famously volunteered his regiment to lead the assault.

Of course, I still have questions.

As it stands, I very briefly mention the encounter and include an endnote that references the sources, including Kate’s book. I do so because I don’t want to make too big a deal about this from Shaw’s perspective.

Let me explain by referring to another point in Kate’s narrative. She writes that Tubman had “probably become quite familiar with Shaw and his regiment since they arrived in Beaufort…”

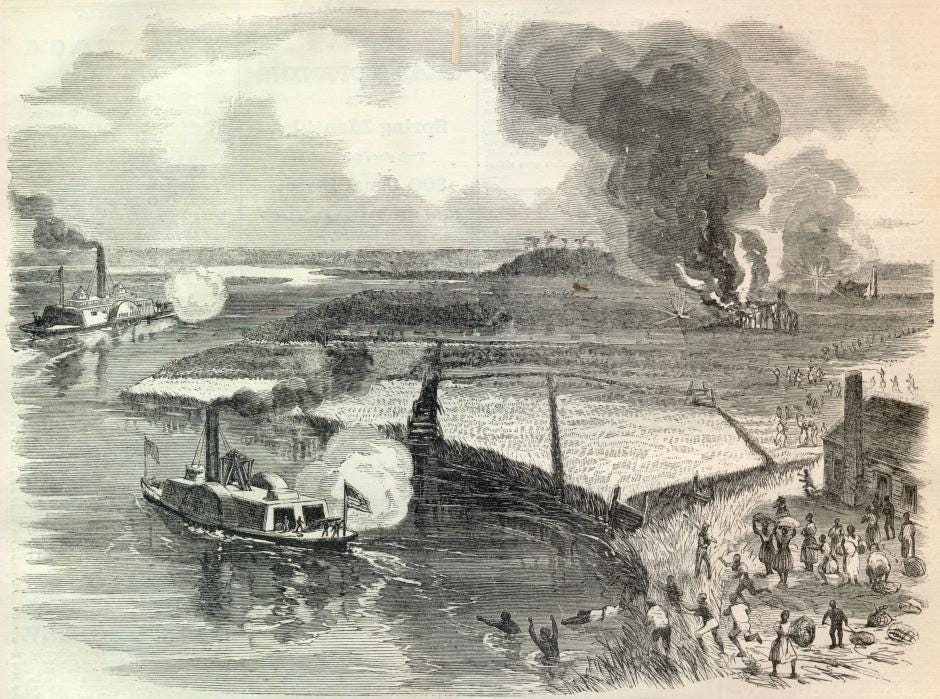

I agree that she was probably familiar with the regiment. Lewis Douglass wrote home to his wife Amelia about seeing Tubman once on June 18 in camp. This is not surprising. She was a notable presence in camp with the 2nd South Carolina under the command of Col. James Montgomery and the two forged a close partnership through a series of raids, most notably during the Combahee River Raid, which took place just before the Fifty-fourth arrived in Beaufort in early June 1863.

[By the way, if you haven’t done so already, pick up a copy of Edda L. Fields-Black’s new book, Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War.]

As a point of comparison, the former slave Susie King Taylor talks about teaching members of the Fifty-fourth to read while they were on Saint Simon’s Island in June 1863.

I also agree that Tubman may have been “familiar” with Shaw, but I do not believe that this acknowledgment was reciprocated. In fact, I am not even sure that Shaw would have been able to identify Tubman. First, Shaw makes no mention of Tubman in his correspondence.

Of course, that alone doesn’t tell us much.

What I do think is important to remember and what I stress in my book is that Shaw took little interest in the Black people that he came across throughout the war. The “Freedom Seekers,” that he came across while he was with the Second Massachusetts in Virginia in 1861-62, were mere curiosities to him. He was never able nor did he ever really try to place his racial assumptions and biases aside. Not much changed when he arrived on the Sea Islands in June 1863.

The one person that he did take the time to mention was Charlotte Forten, who was teaching on St. Helena Island when the Fifty-fourth was briefly encamped there toward the end of June and into early July 1863.

Shaw was clearly attracted to the young educator, but I think what stood out to him most was that she was intelligent and cultured. Despite their racial differences, Forten was the first woman that he had come across during his time in South Carolina that he could hold a conversation with.

On the other hand, Shaw gave little notice to the very people that his and the military’s presence impacted the most.

The other thing that concerns me about the story of Tubman serving Shaw his last meal is that it obscures the much more important partnership between herself and Col. Montgomery.

The Kansas “Jayhawker” was far from perfect. His speech to the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts during the pay-crisis is filled with racist vitriol, but as Todd Mildfelt and David Schafer point out in their new biography, much of Montgomery’s life before the war was guided by a determination to defeat slavery. This stands in sharp contrast with Shaw, who in the 1850s was either traveling and studying overseas, before attending Harvard, all the while desperately searching for a purpose in life.

One of the very few things that I dislike about the movie GLORY is its portrayal of Montgomery. He is as much a villain in the film as are the Confederates. Reading his personal correspondence, it is clear that despite his disagreement with the way the Darien Raid was conducted, Shaw admired Montgomery.

He deserves much better. Despite his shortcomings, Montgomery viewed the war from the beginning as an opportunity to end slavery—a perspective that Shaw never fully embraced. His partnership with Tubman was key to his success during his time along the Sea Islands.

For whatever reason, Harriet Tubman thought it was important to convey the story of having served Shaw his final meal. The story remained meaningful to her even decades after the war. Understanding why is the responsibility of her biographers.

For this Shaw biographer, it turns out the truth of the story isn’t as important as the opportunity it offers to highlight the limitations and blind spots of his subject.

Those limitations are critical to appreciating the trajectory of Shaw’s life and the small place he occupies in a war that ultimately did abolish slavery.

I appreciate this nuanced analysis of the incident remembered by Tubman and not mentioned by Shaw. The context of their respective lives and of others, like Montgomery, illustrate the era's class-centric mores. If what comes to us now can't be conclusive I am happy to be content with KML's scholarship.

What stand out to me, so far: Tubman just six weeks earlier was a de facto federal army officer. (Was she actually under the command of the same Col Montgomery? Had to be.) She was fully able to lead a raid into deep enemy countryside, albeit, that she had numerous local compatriots able to point out where 'torpedoes' (river mines) were planted, and tell dispositions of any White/Rebel forces.

The biographies I have read point underscore Tubman's nerves of steel that enabled her to perform these feats and similar ones on the Underground RR (and boast she'd never lost a passenger), yet with a Magdelene-like willingness to work as a camp servant if it helped the cause. A person showing this fortitude did not need to embroider on the truth. I might imagine she could lie, but only in the context of an enslaved woman speaking to an enslaver, or, as an operative, in an espionage situation (which may have been often). So if she remembered serving a meal to the 54th's colonel, his last one, just how can this be gainsaid?

Shaw was to lead a desperate attack starting at sunset. At dinner, he likely had focused his mind on imminent tasks facing the 54th. And few minutes to record whom he'd seen at his table.

I know basically nothing about the 54th's officers and look forward to KML's biography of Shaw. Certainly the character descriptions of him and Montgomery are worth anticipating the read.

Thank you, Kevin, for exploring this further and laying out some of the evidence. Before I get into that in a little more detail, I noticed in one of your comments to another response that you mention the fact that Tubman was never officially inducted/recruited into the Army - and of course, she could not have been because she was a woman. You and your followers might be very interested to know that the United States Army and the Pentagon are currently working on the reams of paperwork to sponsor legislation that would officially induct Tubman into the Army posthumously (it actually takes an Act of Congress). They are eager to award her a Medal of Honor. This came from inside the military, not via an outside campaign. Tubman may be getting what she has been due all this time!

On another point, I think that as historians we need to be mindful of class and race-based assumptions, then and now, when considering historical records and writing about them. I agree that Shaw likely did not give Tubman much thought, and given the battles ahead of him would not have mentioned her in his writings. It took men like the numerous and powerful abolitionists in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, and military men like Montgomery, Hunter, Gillmore, Higginson, among others, to acknowledge and recognize Tubman and her incredible skills and brilliance and write about her. By drawing attention to the fact that Tubman served Shaw his last meal - a witness to his last hours - does not diminish in any way her incredible work with Montgomery. It is just another aspect of the many, many relationships and endeavors she engaged in during the war.

There is one thing that you wrote that I would like to call out. You write, in reference to Philadelphian Charlotte Forten : "Shaw was clearly attracted to the young educator, but I think what stood out to him most was that she was intelligent and cultured. Despite their racial differences, Forten was the first woman that he had come across during his time in South Carolina that he could hold a conversation with." Ouch. Harriet Tubman was not only intelligent, she was a genius. She did not have formal schooling in that she could not read or write text. What she did have was incredible *literacies*. She could "read" the night sky as well as any mariner. She could "read" the landscape - the forest, the fields, the marshes, streams, rivers, bays, ,and more, so well that she successfully navigated not only hostile and dangerous slave territory in Maryland, but also in South Carolina and Georgia during deadly wartime. She could "read" people, too. As for culture, what you really mean is that Forten was upper-class, and elite, like Shaw. Tubman exuded culture - a culture of extremely confident Black womanhood that drew admirers all races and sex. You were correct, however, when you identify Shaw as a racist. That says it all.