Confronting the Past Should Make Us Uncomfortable

Of all the efforts on the part of state legislatures to regulate the teaching of history, the most baffling is the attempt to ensure that our students do not experience feelings of discomfort. This assumes that teachers have the power to manipulate the emotions of their students, but it also raises the question of what, if anything, is wrong with experiencing discomfort when studying history.

In fact, I would suggest that a good history class should bring out a wide range of emotional responses in our students.

This has been driven home for me time and time again in the classroom and on class trips to historic sites across the country. My experience working with students at a Jewish Day School, in particular, is worth spending some time exploring.

For four straight years I co-led a civil rights-themed tour that in different iterations included stops in Atlanta, Tuskegee, Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham, Jackson, and Memphis. It’s an intense 5-days that, in addition to stops at key historic sites, includes interviews with individuals who participated in the Freedom Rides, the march from Selma to Montgomery, and lawyers who worked to bring legalized segregation to an end.

We also spend a good deal of time at the end of each day reflecting on the significance or meaning of this history for us as Jews.

This last point takes center stage when visiting Montgomery. One of the challenges we face organizing this trip is ensuring that students have access to Kosher food. Thankfully, there is a very welcoming synagogue in Montgomery that is more than happy to host and provide us with a hot meal. We follow up dinner with a meeting with the rabbi.

Keeping with the theme of our trip, the focus of this session is the role of Jewish residents of the city during the civil rights movement. I think our students expect to hear how the Jewish community rallied alongside Montgomery’s Black community to help achieve the goal of civil rights. They are quickly dispelled of this assumption.

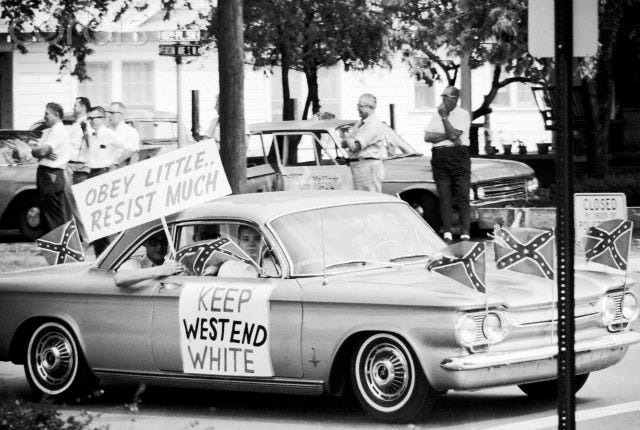

They learn that Montgomery’s Jewish community was, in many ways, part of the broader Jim Crow culture of the time. Jews accepted the racial order of the mid-twentieth century. They lived in white neighborhoods and their ownership of local businesses resulted in placing a high value on maintaining peace within the city limits. No doubt, some supported the efforts of civil rights activists, others may have been sympathetic, but failed to act, and others resisted altogether.

I think for some of our students, the challenge and even shock is in acknowledging that an embrace of the Jewish faith did not preclude defending a culture and political system built on white supremacy. Some students pushed back and suggested that Montgomery’s Jews had abandoned their faith rather than appreciating the extent to which religious identification and practice influence and are influenced by the broader cultures in which we live.

Conversations about this particular issue continued for the rest of the trip and even after we returned home. In these uncomfortable moments the distance between past and present shrinks. In these moments we sometimes catch ourselves reflected in the past. Students are forced to acknowledge the likelihood that they would have behaved in a similar manner, in that particular place and at that particular time.

Studying history can and should do that. It can force us to step outside of ourselves, to look at the world through the eyes of other people who came before us, to whatever extent the historical record permits. What conclusions and connections students make in these moments depends on a wide range of factors, but it often brings out a wide range of emotions, including feelings of discomfort. I have often experienced this in my own reading and research and I’ve learned a great deal as a result.

I welcome these moments and I encourage my students to keep an open heart and mind when confronting the past. It has the potential to make us all better people.