Defenders of the Confederate memorial in Arlington National Cemetery staked their defense on the belief that the memorial represents reconciliation. In fact, a number of people referred to it specifically as the “Reconciliation Monument.” As I have pointed out on numerous occasions, no one referred to it officially as such, including the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who were responsible for its dedication.

People posted newspaper clippings to demonstrate this good will between former enemies in 1914. But in doing so they highlighted their inability to critically evaluate primary sources. What follows is a cautionary tale of getting your history from un-vetted sources

Here is an example of what I mean from Twitter X.

Here is another example from the same Twitter X account. This time it’s the famous photograph of Confederate and Union veterans shaking hands during the 50th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg in 1913.

It's an iconic photograph and for many people it is the clearest example of the good will that former veterans on both sides had for one another. Forgive & forget.

But as historian Thomas Flagel argues, the veterans' primary intention was not to embrace reconciliation at Gettysburg. Many of them remained deeply bitter and were driven by feelings of sectionalism. Most veterans went to Gettysburg, according to Flagel, not to shake hands, but to relive their own experiences. Photographs like the one above were often orchestrated and sometimes difficult to achieve because of these lingering feelings of bitterness.

What this individual has done is little more than cut and paste a couple of primary sources onto Twitter X without any attempt at interpretation. It’s as if the primary sources speak for themselves. No need to know anything other than the words on the page. Let’s be clear, this isn’t doing history.

They fail to evaluate these sources within the rich archive that exists on the subject of reconciliation and also ignore the rich historical scholarship that helps to place these primary sources in context. No references to historians such as Karen Cox, Caroline Janney, David Blight, Keith Harris, and Barbara Gannon. Why? Because they haven’t read them.

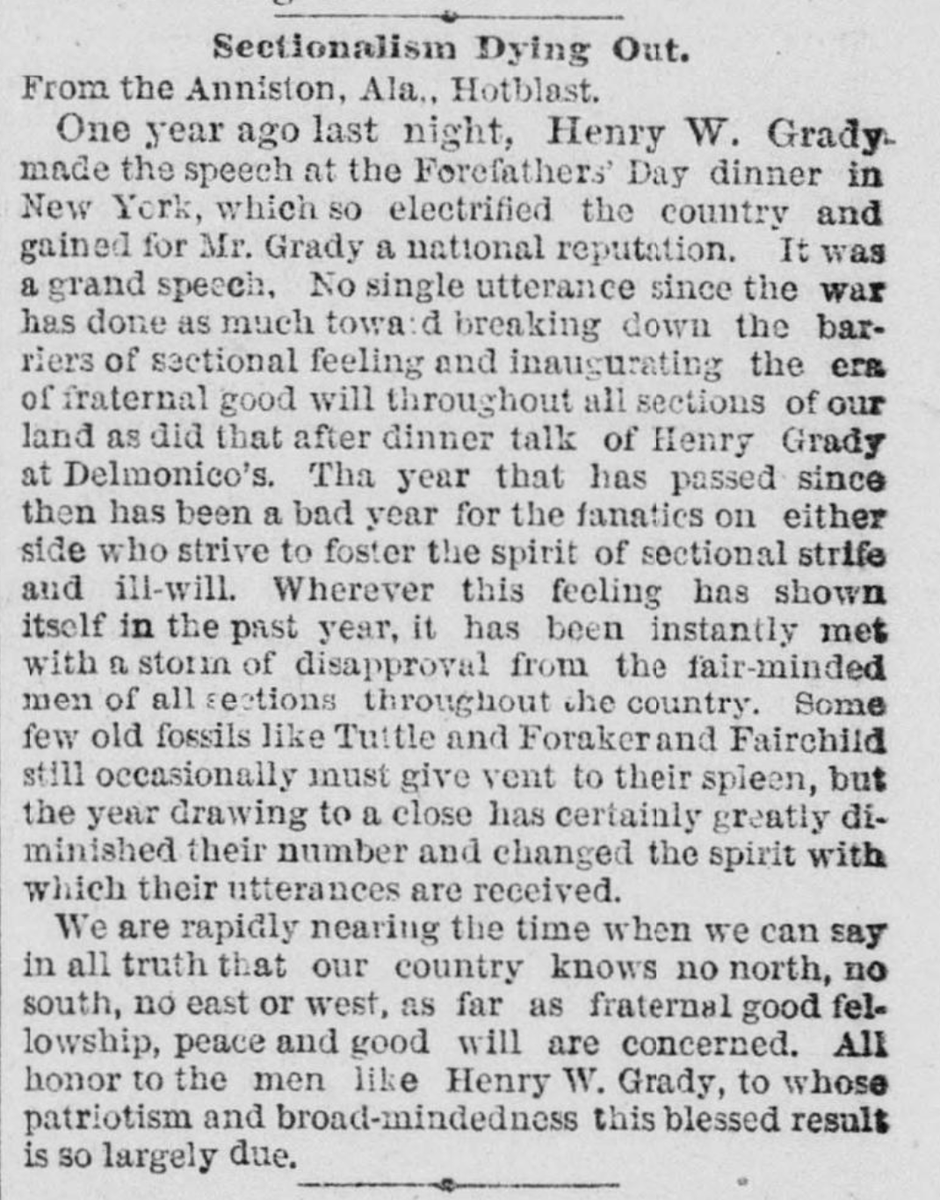

Let's look at another example of how to interpret a newspaper entry that relates to this debate about reconciliation and Civil War memory.

I am sharing this newspaper clipping without any source information to illustrate the point that this is how most of the postings I've seen in recent weeks, in defense of the Confederate monument in Arlington, have been presented.

The first question that we need to answer is source, date, and author, if available. Most newspapers in the nineteenth century were highly partisan and often functioned as official organs of political parties. Appreciating this fact allows us to better understand why certain stories were published or ignored as well as the biases contained within.

If you were just to read the text alone you might think that this is a straightforward story of sectional reconciliation. A Georgian travels to New York City to heap praise on the man who burned a huge swath of Georgia to the ground in 1864. What could be more reconciliationist in spirit than this.

You would be wrong if you came to this conclusion and in doing so have allowed yourself to be deceived by the document and whatever authority you have given to the individual(s) who posted it. This is not just bad history. It isn’t history at all.

Primary sources don't simply reveal historical truth. We must ask questions and investigate further. In other words, we must interpret the document.

Before proceeding, we need to know that this article was published in the Atlanta Constitution on December 27, 1887.

Now that we know where it was published, let’s look at some other possible questions: Who was Henry Grady? What is the political affiliation of this newspaper? What was he doing in New York? Why a speech?

First, we need to know that Grady was quarter-owner and editor of the AJC. He is credited with coining the term "New South," which, by the way, the UDC hated as Moses Ezekiel’s unofficial name for the Arlington Confederate Monument because it implied that there was something wrong with the "Old South."

Grady and other New South boosters were committed to seeing the South industrialize and expand its agricultural economy. To do this they needed northern money. So, this is one of the main reasons why Grady traveled to New York in 1886. Notice that you don’t learn this from the article itself. This is what historians refer to as “historical context” or just “context.”

In the audience that night was J.P. Morgan and other industrialists, along with W.T. Sherman. Grady praised Sherman's generalship, but noted that he was "but a mite careless about fire."

Grady went on to say:

In my native town of Athens is a monument that crowns its central hill — a plain, white shaft. Deep cut into its shining side is a name dear to me above the names of men — that of a brave and simple man who died in brave and simple faith. Not for all the glories of New England, from Plymouth Rock all the way, would I exchange the heritage he left me in his soldier’s death. To the foot of that shaft I shall send my children’s children to reverence him who ennobled their name with his heroic blood. But, sir, speaking from the shadow of that memory which I honor as I do nothing else on earth, I say that the cause in which he suffered and for which he gave his life was adjudged by a higher and fuller wisdom than his or mine, and I am glad that the omniscient God held the balance of battle in His Almighty hand, and that human slavery was swept forever from American soil — that the American Union was saved from the wreck of war.

The New South rested on three pillars: loyalty to the restored Union; recognition by all Americans of the truth of the Lost Cause, and recognition that the South must be left alone to manage race relations.

Of course, I could go on with fleshing this out and provide even more context. If you are really curious, I recommend William Link's book Atlanta, Cradle of the New South.

But with what I have already presented, can we really just reduce this news clipping to a straightforward story of reconciliation or have I done enough to suggest that this is a much more complicated story?

It’s another reminder that reconciliation did not exist in a vacuum. There were competing agendas at work throughout the postwar period. Reconciliation was often a means to an end. Politics and lingering bitterness was always present and often dominated.

Simply plucking out a couple of newspaper clippings from the vast archival record does little more than reinforce prior assumptions and a personal agenda. It bears no resemblance to what engaging in the critical analysis of historical entails.

As difficult as it is, our job as students of history and as historians is to put our assumptions about the past aside. It's not about finding what we hope or need to find in the past, but about honoring the memory of our ancestors. We can do that best by seeking the truth.

“True reconciliation is never cheap,” Desmond Tutu wrote in 1995, when he was appointed to chair South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “It is based on forgiveness which is costly. Forgiveness in turn depends on repentance, which has to be based on an acknowledgment of what was done wrong, and therefore on disclosure of the truth. You cannot forgive what you do not know.”

Dear Mr. Levin,

I just wanted to call you attention to this valuable article:

Opinions | Here’s the Civil War history they didn’t want you to know

The Alabama men who fought for the Union in the Civil War were expunged from history.

Opinion by Howell Raines

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/12/20/howell-raines-alabama-civil-war-history/

Bernard Leikind