Thanks to all of you who shared your thoughts in response to yesterday’s open thread. They were incredibly thoughtful and gave me a great deal to consider. Here are two to consider:

One reader commented that, if done right, contextualization could educate the congregation as well as the broader community. The addition of some kind of monument honoring African Americans was also suggested:

I need to know the context of their contextualization before rendering judgment. I wish it could be removed, but, if done well, I think adding context can better reach those, over time, that would completely protest removal. If not the current generation, then the next. I’d also think an offsetting monument is required for those forgotten by this “honor”, African Americans or other Americans that courageous fought the rightful cause.

Another reader concluded that the plaque should be removed and melted down and offered this explanation as to why:

The plaque should be removed, melted down and in its place a new one added that reads:

‘Behind this plaque once hung another plaque that was affixed to this wall to celebrate the myth of Southern courage and bravery of those who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The plaque was hung by the church out of ignorance and hate in an effort to continue centuries of oppression and brutality against African Americans.

The Bruton Parish Episcopal Church apologizes to the enslaved people of this country and their descendants. The parishioners of this church will forever reflect on the hypocrisy of the meaning of such a plaque against the very values we espouse.’

I don’t know the answer to the question posed in this post’s title. What I do know is that whatever answer we or the Bruton Parish community arrive at it should be informed by a deep understanding of the relevant history.

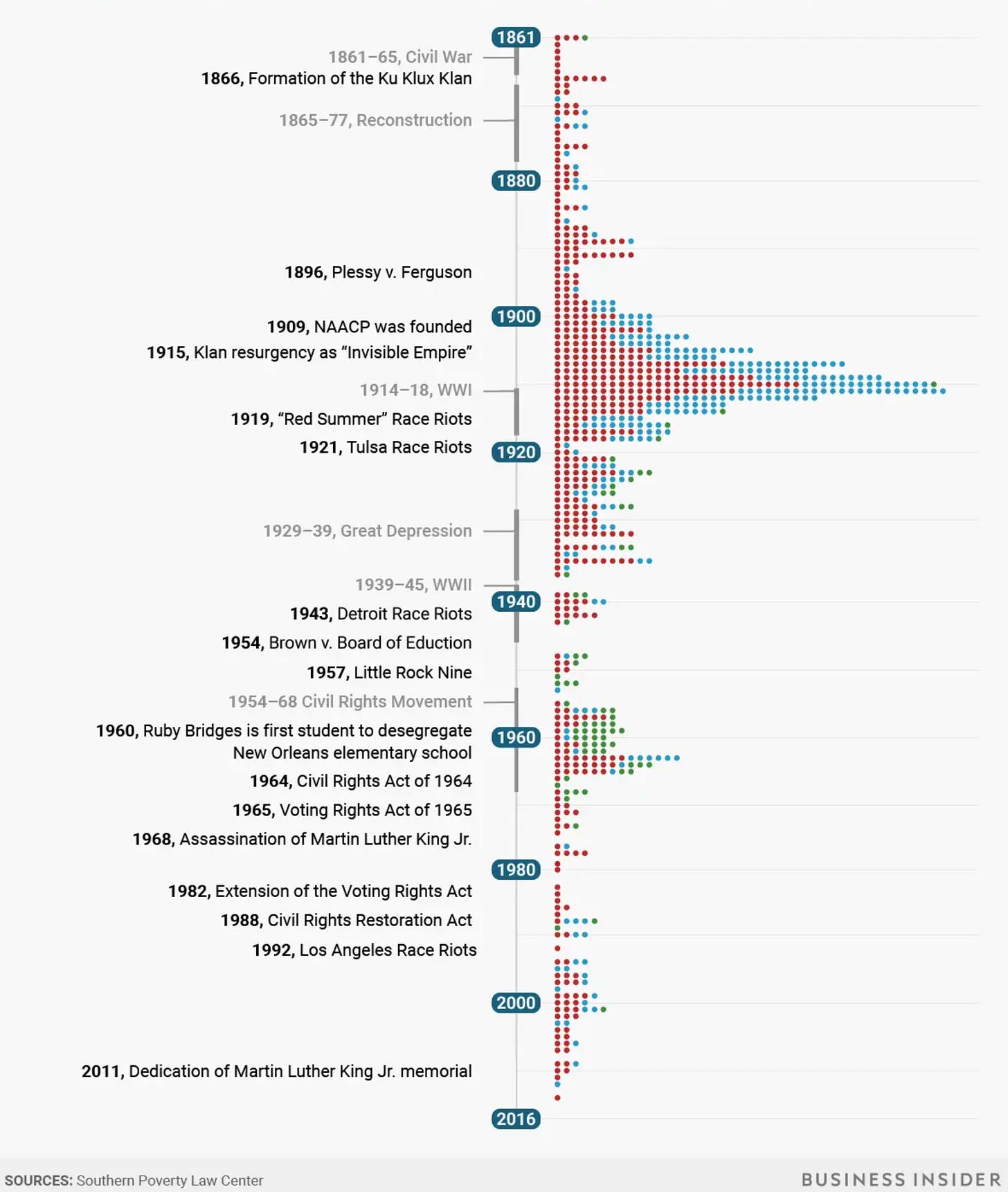

Unfortunately, I think this has been made even more difficult by our tendency to reduce the long history of Confederate memorialization to the height of the Jim Crow era (roughly 1890-1930) and the nadir of race relations in the United States.

Certainly the history of slavery and race looms large over efforts to commemorate the Confederacy in any era and for the obvious reasons, beginning with the fact that the Confederates were fighting to create an independent slaveholding republic.

However, if we ignore the importance of change over time and ignore the complexity of history we obscure important information. The plaque honoring the Confederate dead in Bruton Parish Episcopal Church in Williamsburg, Virginia is not a product of the Jim Crow era. It was not placed in front of a courthouse or in a public park by the United Daughters of the Confederacy as an explicit expression of white supremacy and white solidarity.

It was the product of one woman’s memory of wounded and dying men that had taken refuge on church grounds during the Peninsula Campaign of 1862.

Isabella Thompson Sully comforted Confederate wounded being treated after the May 5, 1862, Battle of Williamsburg in churches serving as hospitals. Outside the Baptist church, and between it and the Powder Horn, she saw bodies of ‘men who died in the night and which the enemy were about to bury in the open.’ Before she and her brother, Philip Montegu Thompson, a prominent Williamsburg lawyer, could interfere, the dead were buried, unidentified, in pits.

Inside the sanctuary — a scene Sully later described as that of ‘horror and confusion’ — wounded Confederates expressed to her fear ‘of being thrown into these pits without Christian burial.’ She made note of their names and regiments; she promised them that if they died, ‘I would have their bones placed in consecrated ground.’ She estimated there may have been 100 bodies.

After the war, Sully, in Richmond, solicited donations ‘to redeem my promise’ and sought permission to reinter the remains in Bruton Parish Churchyard near Confederate graves. She collected $212. She hired a ‘Mr. Pearce,’ who opened the pits, filled boxes five feet long of intermingled bones and laid them to rest in a mass grave along the cemetery’s north wall.

The plaque was present in the church as early as 1882, which places it well outside the flurry of monument dedications during the Jim Crow era. It is a product of the experience and memory of grief, trauma, and loss. It fits into the first wave of monument dedications in local cemeteries, organized by the Ladies Memorial Association, in the period immediately following the war.

This is not to suggest that slavery, race, and the Lost Cause are not relevant factors in understanding this story. They most certainly are relevant, but they may not be the most important factors.

I’ve maintained from the beginning that the contextualization of Confederate monuments is tricky. I think there is an opportunity to do it at Civil War battlefields, overseen by the National Park Service, like Gettysburg. I believe it can be done with monuments that have been relocated to museums.

It is next to impossible to do it in prominent public spaces that are intended to be welcoming to all residents. The problem here is that contextualization does not solve the fundamental problem that these specific monuments pose to the community.

Then there are all kinds of other scenarios that need to be carefully considered.

Can it be done in Bruton Parish Church? We shall see, but what I do know is that context and history matter.

Like what you’ve read? Subscribe to the newsletter and your email will be entered to win one of two copies of my book, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. Winners announced tomorrow evening. Good luck.

There are some important omissions from that chart, namely the 50th and 100th anniversaries of the Civil War, when interest was high and people were looking back at that history. The two largest peaks of monument construction took place in the lead up to and during those anniversary years, particularly the 50th anniversary when many of the veterans were still alive. Those are significant facts that are not noted at all in your list of nothing but race-related events. Are you seriously arguing that race alone was the inspiration for constructing Confederate monuments? And how does that explain Union monuments going up at the same time and in similar numbers?

A very thought provoking piece. I think there is a different conversation to be had when the memorial relates to a war grave particularly if it’s contemporary of the burial, rather than one that merely commemorates soldiers, their service, or a battle.

The issue of what we owe the dead of our enemy can be a vexed one. With reconciliation former enemies can make the sort of peace that allows for the (misattributed) Ataturk Gallipoli speech. Sadly for the US, reconciliation post the Civil War never happened so it remains vexed.