Yesterday a new exhibit about the history of slavery in Boston opened at Faneuil Hall. The site is one of the most popular stops on the city’s Freedom Trail, which means that the exhibit will likely be seen by a significant number of visitors this summer. It’s another important step in Boston’s reckoning with a past that has long been hidden behind the public memory of the American Revolution, featured at places like the site of the Boston Massacre, Paul Revere’s home, and Bunker Hill, to name just a few.

However, not everyone was celebrating the new exhibit. A small group from the New Democracy Coalition, led by Reverend Kevin Peterson had this to say:

We do not object to this exhibit being placed at another site,. But we respectfully insist that Mayor Wu remove these artifacts from a place named after a white supremacist. History tells us that Peter Faneuil was a bigot. His name should not adorn a publicly owned building.

Peter Faneuil was more than a bigot.

At the time of his death, Peter Faneuil’s ‘very ample fortune’ made him one of the wealthiest people in Boston. Similar to the majority of Boston’s colonial elite, Faneuil made his money through trade in the Atlantic world. This network of Transatlantic Trade proved extremely lucrative in part because of the institution of slavery. Merchants such as Faneuil built their financial empires by trafficking enslaved individuals and trading goods consumed and produced by enslaved labor. Though Faneuil cannot be characterized as a major slave trader, his complicity in this system offers a window into the Transatlantic economy of 1700s Boston.

In May the organization demanded that the city change the name of Faneuil Hall. This is not the first time that local activists have called for a name change.

I understand their reasoning, but I think it is a mistake since it obscures an important part of the history of the site that would be lost with a change in name.

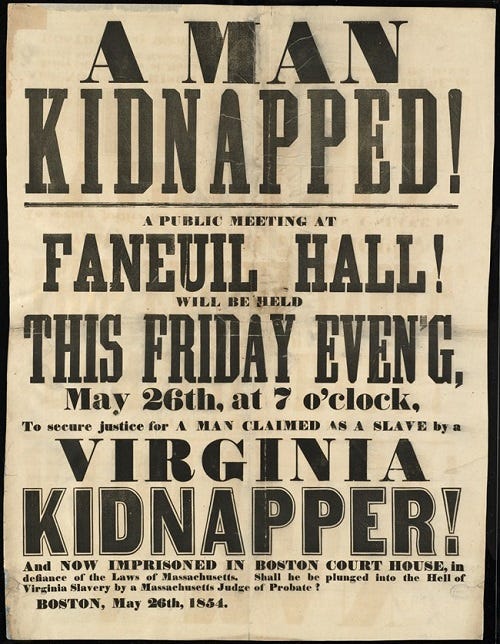

Black Bostonians rallied inside Faneuil Hall throughout the nineteenth century to call for the end of slavery and civil rights. Local Black leaders such as William Wells Brown, Lewis Hayden, William Christopher Nell as well as national leaders such as Frederick Douglass routinely took to the stage to speak out and issue demands.

They had long ago appropriated the space inside a building named in honor of a slave trader for their own purposes. This is the history that should be highlighted and celebrated by everyone in Boston.

Every time a Black man or woman walked through the door of Faneuil Hall a statement was made that history could be overcome—that radical change was possible.

This new exhibit about the history of slavery in Boston is part of that process. It is more than a simple attempt at education or public history. The exhibit itself is a form of protest that forces us to confront not just the history of one slave trader, but the extent to which the city has long ignored this crucial aspect of its past.

One person who does get it is Kyera Singleton, co-curator of the exhibit and executive director of the historic Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, a Colonial estate that held the largest number of slaves in Massachusetts.

It forces people to contend with the fact that enslaved women, men, and children were integral to the building of Boston. It really does put Peter Faneuil in context as a slave trader and an enslaver. It’s no longer about the building just being the Cradle of Liberty.

Singleton is absolutely right that the exhibit will force visitors to contend with the history of slavery in the city for the first time.

Of course, everyone is entitled to their opinion about the appropriateness of this exhibit, but I disagree with protesters who see it as “less about us being free, and more about us being slaves.”

The history of slavery in Boston is most definitely a story of violence and separation, but it is also a story of survival and a committment to freedom that outlasted the institution of slavery in Massachusetts.

That’s a story that every resident of the city and visitor should know something about and embrace.

I have to confess to lifting this from the Saratoga National Military Parks’ facebook page but I thought it interesting and worth sharing in light of Kevin’s post.

This is Peter Salem day in Framingham MA. The town declared this so in 1882 and has celebrated it annually since. He is described as a soldier of the Revolution having fought in most of the major battles in the northern theater from Lexington and Concorde to Monmouth and Stony Point. He died in the early 1800s in the Framingham Poor House.

This is the inscription on his grave marker:

Peter Salem

Soldier of the Revolution

Concord

Bunker Hill

Saratoga

Died August 16, 1816

Erected by the Town 1882

What this does not say is he was born into slavery in MA in 1750 and emancipated early in the Revolutionary War, this information comes from the NPS at the Saratoga National Military Park.

I think it matters that this person was a free Black Man serving, I assume, initially in the MA Militia and later in a regiment of the Massachusetts Line.

I think the same is true with the Faneuil Hall structure and the person it is named after. Understanding the complete role both played in the development of Boston is important to what the community is today.

Interesting. Those are facts I've either never known or completely forgotten about. I lived in Boston for two years while at Sloan for my master's degree (TMI? eh ...). I visited Faneuil Hall a couple of times. I don't remember there being any noticeable plaque about the Hall's history as a place where humans were bought and sold. I think it's a history (and Faneuil's) that deserves to be preserved and posted throughout the structure, almost like a stations of the cross, but stations of the slave trade. I'm sure there's a more elegant way to phrase that. Keep Faneuil's story alive by telling displaying that story within (also outside!) the very walls where the tragedies took place. This is American history.

I began this by stating I may have forgotten about Faneuil Hall's history in the slave trade. I'm sure that might be surprising to some. Let me share this -- as a Black person who has studied slavery as a college student and simply living in this skin and culture, the number of places and spaces of significance to the slave trade in places I've lived is innumerable. For the record, those are Washington, DC; VIrginia; New Orleans; Boston; New York City (my father is from southern Maryland and I'm a 3rd gen property owner there). This history is everywhere. Forgetting isn't remarkable, especially for someone my age -- that's why we need those damned plaques. LOL!