Congratulations to historian Edda L. Fields-Black on winning the 2025 Gilder-Lehrman Lincoln Prize for her book, Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War. The competition this year was particularly tight.

In the spring of 1862, Harriet Tubman traveled to the South Carolina Sea Islands to assist thousands of formerly enslaved people as they transitioned from slavery to freedom following the military occupation of the region in November 1861.

In Beaufort, South Carolina, Tubman served the Union army in numerous capacities. She served as a scout, spy, and nurse and assisted in the recruitment of Black soldiers.

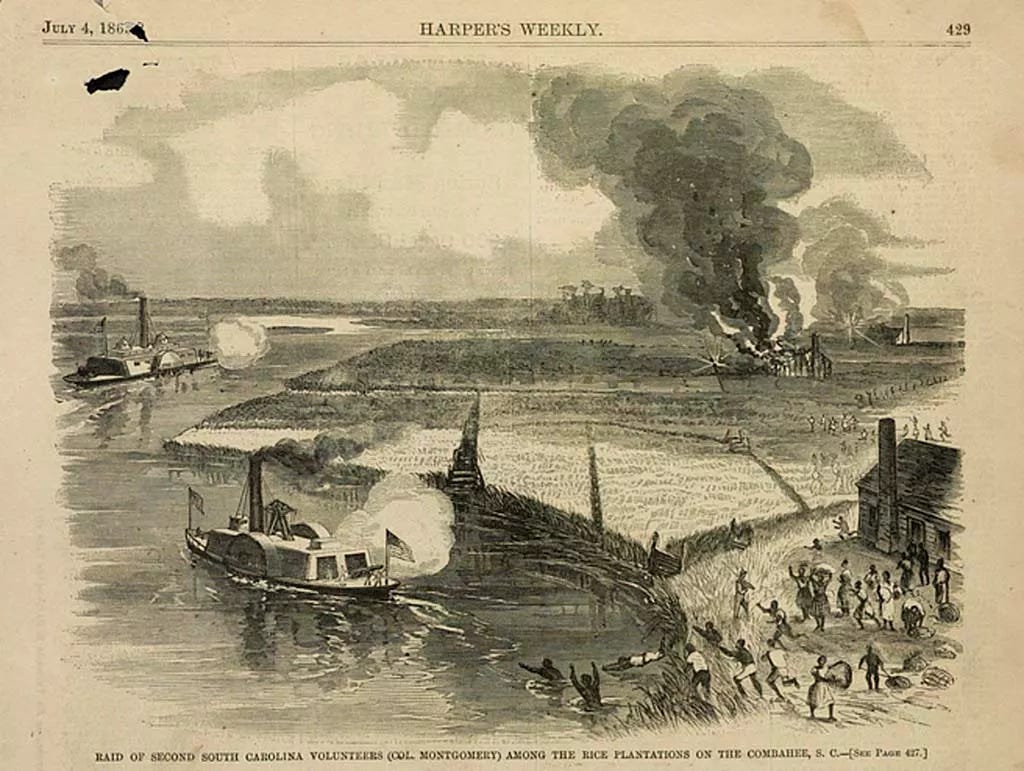

On June 2, 1863, Tubman piloted two regiments of Black US Army soldiers, including the Second South Carolina Volunteers, under the command of Col. James Montgomery, up coastal South Carolina's Combahee River in three gunboats. In a matter of hours, they torched eight rice plantations and liberated 730 people.

The Combahee Raid was the largest among a number of coastal strikes involving Black soldiers, that was led by Montgomery and Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who commanded the First South Carolina Volunteers, in 1862 and 1863. These raids weakened Confederate resistance along the coast and parts inland in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The raids liberated thousands of enslaved people, denying the Confederacy a crucial resource and which helped to fill the ranks of Black regiments.

Her research is impressive. Fields-Black’s mining of the pension records and a wealth of other sources highlights Tubman’s work along the Sea Coast Island as well as the formerly enslaved men, who joined the army, took part in the raid and who settled with their families in the area after the war. Combee reveals how the US military and the enslaved population collaborated to transform the region, how it led to the ultimate fall of Charleston, and ultimately led to the defeat of the Confederacy.

It was a significant military victory, but we rarely frame the Combahee Raid as a battle. We could and according to historian Thavolia Glymph, we should.

Glymph asks: “[W]hat insights into war and war casualties or combatants and noncombatants might be gained if historians studied and walked battlefields on plantations or in refugee camps as they do Gettysburg?”

I think, too, of the Combahee Ferry Raid, remembered today primarily for the rescue of more than 700 enslaved people by Harriet Tubman and US soldiers. It is rarely mentioned that it was also a battlefield—and a mappable one—even though US forces that included Black soldiers burned several plantations, mills, and rice crops, and enslaved people fought Confederate soldiers who tried to prevent their escape. And even though an officer admitted that Confederate forces had allowed ‘the enemy to come up to them unawares, and then retreated without offering resistance or firing a gun, allowing a parcel of negro wretches, calling themselves soldiers, with a few degraded whites, to march unmolested, with the incendiary torch, to rob, destroy, and burn a large section of the country.’

We are talking here about a battlefield where Confederate cavalry used ‘negro dogs’ to prevent Black people from escaping, where a Confederate officer stated in his report of the affair that a ‘negro girl’ had come within yards of reaching a US boat and making it to freedom but that he ordered her to stop and, when she refused, shot her; she got up and ran back to the others who had also been thwarted in their attempt to board the boat. Despite the bungled Confederate response to the US raid, the vast majority of Black people on the Combahee River plantations remained enslaved. Some 30 people from Charles Lowndes’s Oakland plantation were captured by a company of Confederate soldiers as they tried to make their escape. At Field’s Point, the Confederate commander ‘discovered a good many negroes standing in the edge of the swamp, commanded by one white man’ and ‘ordered the artillery to fire into them,’ which it did ‘several times.’ At the Heyward plantation, Confederate forces fired on the ‘stolen negroes’ fleeing to the US gunboat Blake. In the aftermath of the raid, Confederate pickets in the area were reinforced, a move slaveholder Mary Elliott praised. ‘I am very glad to hear of the new picket arrangement for guarding the negroes and trust it may arrest desertion on their part—it would be ruinous to have more of such raids as the [Combahee],’ she wrote.

It’s a provocative point. On a recent visit to the region, the closest I came to the site of the raid was driving on the highway between Charleston and Beaufort and coming across a historical marker on the side of the road near the Harriet Tubman Bridge. I certainly understand that touring this particular military engagement poses numerous logistical challenges. That said, it was frustrating not being able to get up close to specific sites, to better understand the topographical challenges that Tubman, Montgomery and the rest of the command faced, the movement and disposition of troops, the ebb and flow of the fighting, and the raid’s military significance.

In addition to the Combahee Raid, we can also apply Glymph’s framework to Gen. William T. Sherman’s campaign through Georgia in November-December 1864. While “Sherman’s March” is best remembered and often misremembered for the path of destruction cut across the state, historians are now focusing in on the campaign’s impact on the enslaved population.

According to historian Bennett Parten, author of the fascinating new study, Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman's March and the Story of America's Largest Emancipation, the Union army’s march through numerous plantations provided the impetus for upwards of 20,000 slaves to ‘free themselves.’ Parten maintains that Sherman’s Georgia march was the largest example of military emancipation of the entire war.

[Note: The first meeting of the Civil War Memory Book Club will take place on Substack live on Sunday, March 30 at 8 PM EST. We will be discussing Parten’s new book. It promises to be a lively discussion, but it is open only to paid subscribers. Upgrade and get your copy of Parten’s book today.]

The great battlefields such as Gettysburg, Shiloh, Antietam, and Fredericksburg occupy a central place in our popular memory of the war and the way we mark change over the course of the Civil War. Americans paid close attention to the ebb and flow of battles and campaigns and we should as well.

Thankfully, many of these battlefield sites have been reimagined and reinterpreted in recent years to answer new questions and to help visitors connect to the past and find meaning.

But perhaps there are battlefields out there that have yet to be imagined that have the potential to expand and deepen our understanding of the Civil War even further.

Fascinating. Don’t mess with General Tubman!

This looks like a great read