Bias in History: or How I Learned To Leave That "Noble Dream" Behind

I greatly enjoyed reading Evan Portman’s contribution to a series of posts over at Emerging Civil War on the many ethical questions surrounding the researching, writing, and consumption of history.

Evan addressed his concerns about the impact of bias on the production of history.

Here is a little taste from his post to get us started:

How do we remain unbiased, but also value our own backgrounds and what we bring to the table? How can we learn from history while also keeping in mind that we too will be judged by history? Is history an objective science or a subjective art? These are just some of the ethical questions that confront me (and probably others) as I begin my career as a historian.

Bias is perhaps the slipperiest of slopes when it comes to practicing history. It’s undeniable that everyone brings some sort of bias to the table, whether it’s in the form of preconceived notions about a historical figure or simply part of your personal background. Sometimes bias can be harmless or even good.

Let me suggest that while I think this is a perfectly appropriate topic for an Emerging historian to explore, these concerns are largely misplaced. I’ll come back to this in a minute.

Evan applauds historian Allen Guelzo for admitting his bias at the outset in his new biography of Robert E. Lee:

I think the first step in this balancing act is acknowledging our own biases. Historian Allen Guelzo does this well in his biography of Robert E. Lee. Guelzo squarely admits that ‘being a Yankee from Yankeeland’ proves a difficult hurdle to interpreting Lee’s life ‘as he was in the days that he lived.’ Despite whatever preconceived notions Guelzo might have harbored against Lee, he proceeds to interpret the Confederate leader fairly and forthrightly, even showing compassion to the general at times.

While we could applaud Guelzo for the personal revelation at the outset of his book, it shouldn’t have any impact on how the reader judges its content and interpretation. Any survey of Civil War memory demonstrates that there is no strict regional divide over how Americans think about or remember Robert E. Lee. “Yankeeland” is just as diverse in thought as “Dixieland,” whatever these vague terms are supposed to signify.

I’ve recommended Guelzo’s Lee biography plenty of times since its publication. It’s a fantastic book, but if I were to judge the author’s personal background I may not ever have picked it up. After all, Guelzo accepted an invitation to serve on Donald Trump’s 1776 Commission at the end of his first term in office.

Doesn’t this reflect as troubling a bias as compared to a vague admission of where he grew up?

This brings me back to Evan’s initial concerns.

I welcome bias in all its forms. This opportunity to learn and grow from others is fueled by bias, which I take to be the human condition itself.

I expect it to color every aspect of the research and writing of a work of history. You should too. To wish for anything else assumes the existence of some nebulous notion of objective truth, a “Noble Dream” embraced as the hallmark of the professional historical community by the beginning of the twentieth century.

Let it go.

My personal library includes some 1,500 volumes. I can tell you next to nothing about the personal backgrounds and political affiliations of the vast majority of the authors. And you know what? I don’t care. None of it is relevant to me when I read a work of history.

What I care about is how well the author practices the historian’s craft. How did the historian arrive at his or her questions? What kinds of evidence was marshaled in an attempt to answer those questions and how was the evidence interpreted? Did the historian consider the bias or selectivity of the archive itself? Did the historian engage a broader historiography as a means to test an argument or interpretation and in recognition that all historical works must be seen as in conversation with one another? Finally, is the narrative and argument communicated clearly enough through the written word?

The reason I recommend Guelzo’s biography of Lee is not because I believe that he has transcended or successfully set his admitted bias to the side, but because he is a master practitioner of the historian’s craft.

Bias colors every aspect of this process. It is the reason why we are never finished interpreting the past and why it is imperative that we have as diverse a body of people among our historians.

Do I have biases? Of course. One of them is that I am genuinely curious about the past and have a deep desire to answer the many questions that I have about it. Some take a few hours to answer and some, like my forthcoming biography of Robert Gould Shaw, took roughly five years. I have plenty of other biases that stem from my personal background and how I judge the world around me.

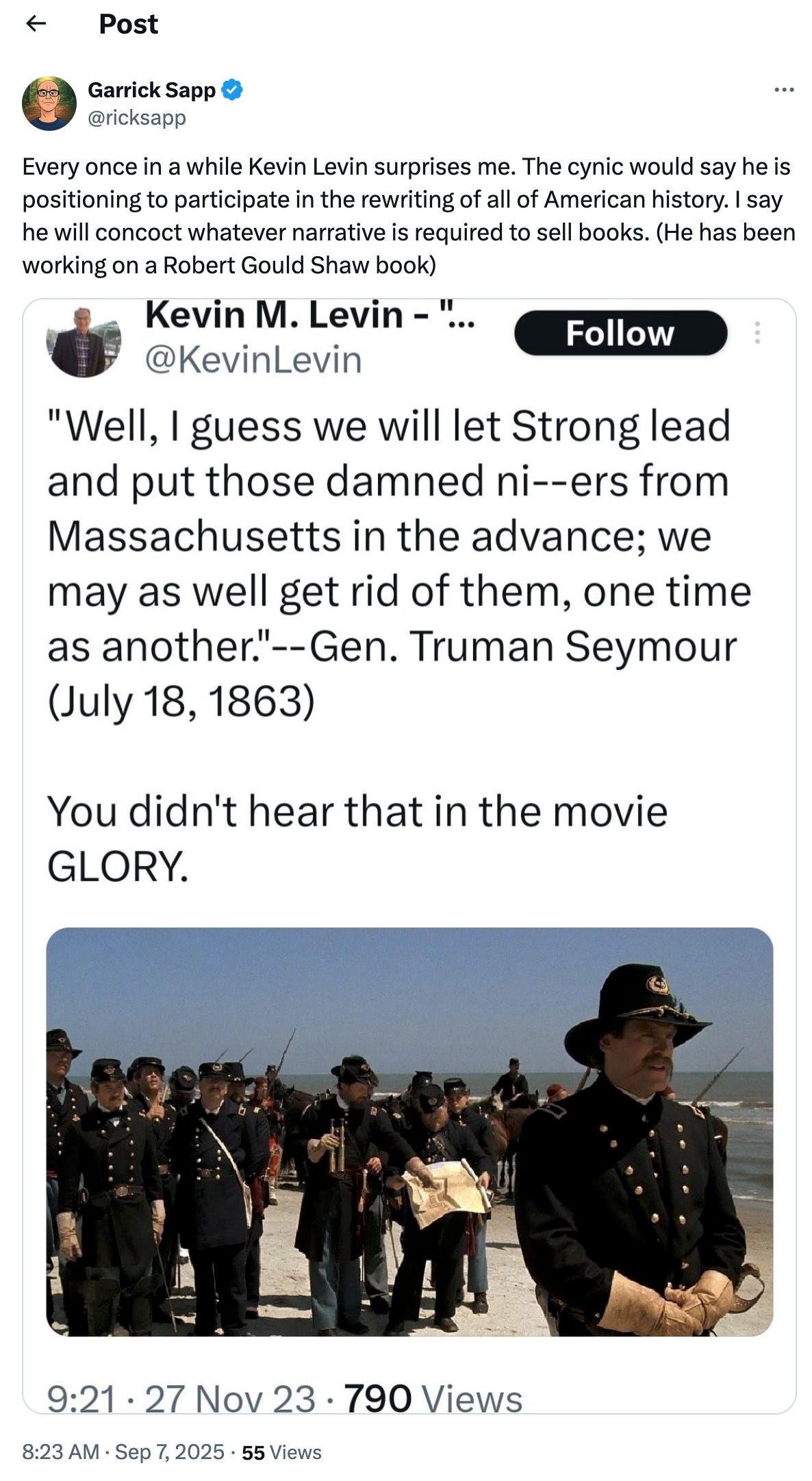

I feel sorry for people who judge others based on their assumptions about what motivates them to write history. Consider this tweet from one of my fans.

Imagine going this far to try to rationalize why I would post something like this or include it in my book. It points to someone who believes that the study of history is nothing more than an expression of political or ideological conviction. Hopeless.

When I read a history book I want to be surprised. I want to be introduced to new questions, new evidence and new ways of interpreting traditional sources. Most importantly, I want to learn new things and be forced to think critically about what I currently believe.

If your understanding of the Civil War or any subject in history that you have spent a significant amount of time exploring hasn’t changed or evolved significantly over the years, you are doing something wrong.

The fuel behind that intellectual journey is bias.

Kevin,

This is a great column. You are right about bias and how we have to work as historians to be as dispassionate as we can as we write history. He haven’t read Guelzo’s book on Lee yet, I have appreciated his other books, but I didn’t know of his association with the 1776 Project, but like you I believe that he is a master in his crafting of history. I won’t let his association with the 1776 Project influence my view of his work. I really like how you are handling your Shaw biography. Hagiography is not history. As much as I admire Shaw, he was a man of his times who had many of the same prejudices as others of his time.

Thank you for this article. All the best,

Steve Dundas

Excellent. Just excellent.