In the summer of 2020, following the police murder of George Floyd, Augusta, Georgia Mayor Hardie Davis created the Task Force on Confederate Monuments, Street Names and Landmarks. The commission was created to study public spaces in the community that honored the Confederacy and Confederate leaders.

At the top of their list was the huge Confederate monument located in downtown Augusta on Broad Street.

A few months later the panel returned a final report to the mayor with a recommendation that the monument be relocated to the grounds of either Magnolia Cemetery or Westview Cemetery.

No action has been taken.

I have suggested more than once that Confederate monuments and memorials dedicated during the Jim Crow era need to be understood, in part, as a response to Reconstruction and the gradual push to reestablish white control.

The proliferation of monuments in public spaces (in contrast with earlier monument dedications located in cemeteries) connected a new generation of white southerners with their parents and grandparents who experienced the war years and now served as a rallying cry for white unity during the Jim Crow era.

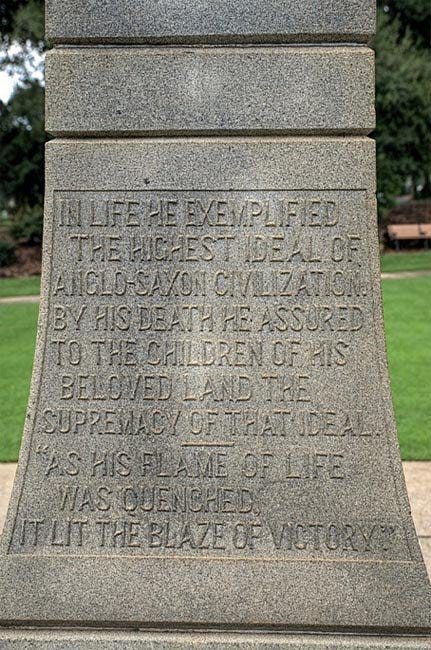

As anyone who has studied this subject knows, white southerners celebrated the return of white rule in their monument dedication addresses and on the monuments themselves.

Augusta’s Confederate monument is an interesting case in point given the timing of its dedication. It was dedicated on October 31, 1878, just one year after the formal end of Reconstruction, but a closer look allows us to see it as part of this turbulent and violent period in American history.

First, the monument’s inscription is instructive, which reads in part: “No nation rose so white and fair, none fell so pure of crime.”

Around the base of the monument are life size statues of four Confederate generals: Thomas R. R. Cobb, Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and William H. T. Walker.

Like most of these celebrations, the dedication of Augusta’s Confederate monument would have brought out most of the city’s white population as well as from the surrounding area. The local Ladies Memorial Association raised the funds for the monument and helped to plan the event itself.

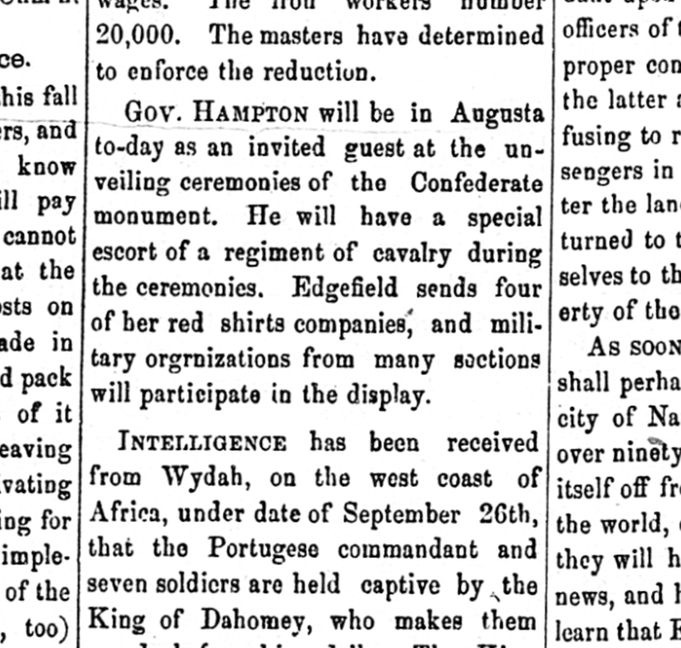

While searching newspaper articles about the dedication of the monument I learned more about who attended. Interestingly, it included former Confederate general and governor of South Carolina, Wade Hampton. The crowd also included four companies of Red Shirts from Edgefield, South Carolina.

The Red Shirts functioned as the paramilitary arm of the Democratic Party. Like the Ku Klux Klan, the Red Shirts challenged Military Reconstruction and wreaked havoc on Black communities.

But why was the governor of South Carolina as well as the Red Shirts in Georgia for this particular monument dedication?

Historian Bruce Baker helped me make the connection. Two years earlier in July the Hamburg Massacre took place just across the Savannah River from Augusta in the small, but predominantly African-American village. [You can read a thorough account by historian Stephen Berry.]

On July 4, 1876, members of the local all-Black unit of the state militia paraded down Hamburg’s Main Street to celebrate the centennial of America’s independence. During the celebration two young white men in a horse-drawn buggy rode toward the troops and demanded to pass through. Following a standoff, the two men were allowed to continue through town.

Four days later, hundreds of armed white men, including members of the Red Shirts, arrived in Hamburg, led by a former Confederate general, demanding that the militia unit disarm. A small cannon was shipped across the Savannah River from Georgia to reinforce the white vigilantes.

Militia members were eventually forced to retreat to a stone warehouse which they used as their armory. In the end, twenty-five men were captured and six were murdered.

The massacre in Hamburg was one of hundreds of such attacks against African Americans during Reconstruction.

According to Hampton biographer, Rod Andrew Jr., “the tragedy led indirectly to his nomination for governor.” In October 1878 Hampton was in the midst of a reelection campaign, which he went on to win.

Hampton’s presence at the dedication ceremony could easily be seen as just another campaign stop, but the presence of the Red Shirts may perhaps be interpreted as a collective “Thank You” to the people of Augusta.

With Hamburg still fresh in the minds of local residents, the presence of the governor and Red Shirts was a show of solidarity between white Georgians and South Carolinians in their commitment to reimposing white rule in their respective states.

The cheers and martial music that rang out that October day in Augusta were not in recognition of a dead past, but a rallying cry for the work that would need to continue to ensure that a “nation so white and fair” did not die in vain.

Postscript

Thanks to historian David W. Dangerfield for sharing the story of the dedication of the Meriwether Monument in 1916 at John C. Calhoun Park in North Augusta, South Carolina. The monument commemorates Thomas McKie Meriwether, the only white man killed in the Hamburg massacre.

Wow! Your article weaves the politics of two states, the Red Shirts, the horrible massacre of African Americans in Hamburg and today's Confederate monuments. I had read about Wade Hampton in "Rebellion, Reconstruction, and Redemption, 1861-1893: History of Beaufort County, South Carolina" by Stephen Wise and Lawrence Rowland, but Hampton's attendance at this monument's event is new to me. This Confederate monument has not been pulled down, but in a complex way still instructs us on the past today. A further question is demanded. Is there a monument or something for the African Americans murdered at Hamburg? That would instruct us today while honoring the victims and their humanity.

Kevin,

Thank you for this excellent article about the Augusta Confederate monument. Unlike most of the monuments erected during the “Redemption” period, this one is unique as the statues were of real people and not mass produced. The bulk of the monuments featured a generic infantry soldier and were produced in the north and sold for $400. They dot the Southern landscape. The people are interesting for what they represent. Lee and Jackson have no connection to Georgia, but are two thirds of the trinity of major “saints” of the Lost Cause Myth, the third being Jefferson Davis. Davis and Howell Cobb despised each other. Cobb was a leading secessionist, and opposed Davis in the vote to become President of the Confederate States. Cobb entered the Confederate Army, eventually becoming a Major General. He stridently opposed Lee’s last minute support of a move to enlist Black soldiers in February and March of 1865. He was an opponent of Reconstruction and died on a speaking tour while in New York in 1868. Prior to the war he was a long term member of the House of Representatives, and Speaker of the House. His portrait was removed from public display in the House in 2020. Walker, a Georgian, was like Lee on active duty in the U.S. Army and resigned his commission at the beginning of the war. He opposed and exposed General Patrick Cleburne’s plan to emancipate Slaves and allow them to serve in the military in early 1864. He was killed in the Atlanta campaign. I cover the latter in my book, “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: Religion and the Politics of Race in the Civil War Era and Beyond,” published by Potomac Books an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, October 2022. Honestly, I am surprised that the monument still remains.