Last week I visited Arlington National Cemetery. It was my first visit since the Confederate memorial was removed in December 2023. As a result, Section 16 is now a little more difficult to find since one of the largest commemorative structures in the entire cemetery no longer stands.

All that is left is the large pedestal that now looks wildly out of place amidst the grave markers. It is unclear as to whether it will ever be used again in any capacity or whether, in time, it will also be removed. My guess is that this will be determined by whether its removal can be accomplished without disturbing the nearby graves.

I didn’t know how I would feel on this particular visit. The memorial has become so familiar to me having used it many times to help groups better understand Civil War memory. I will miss being able to use it as a teaching tool but, of course, I understand why it was removed.

Perhaps there will be an opportunity at some point to utilize parts of it again in a more appropriate setting such as a museum.

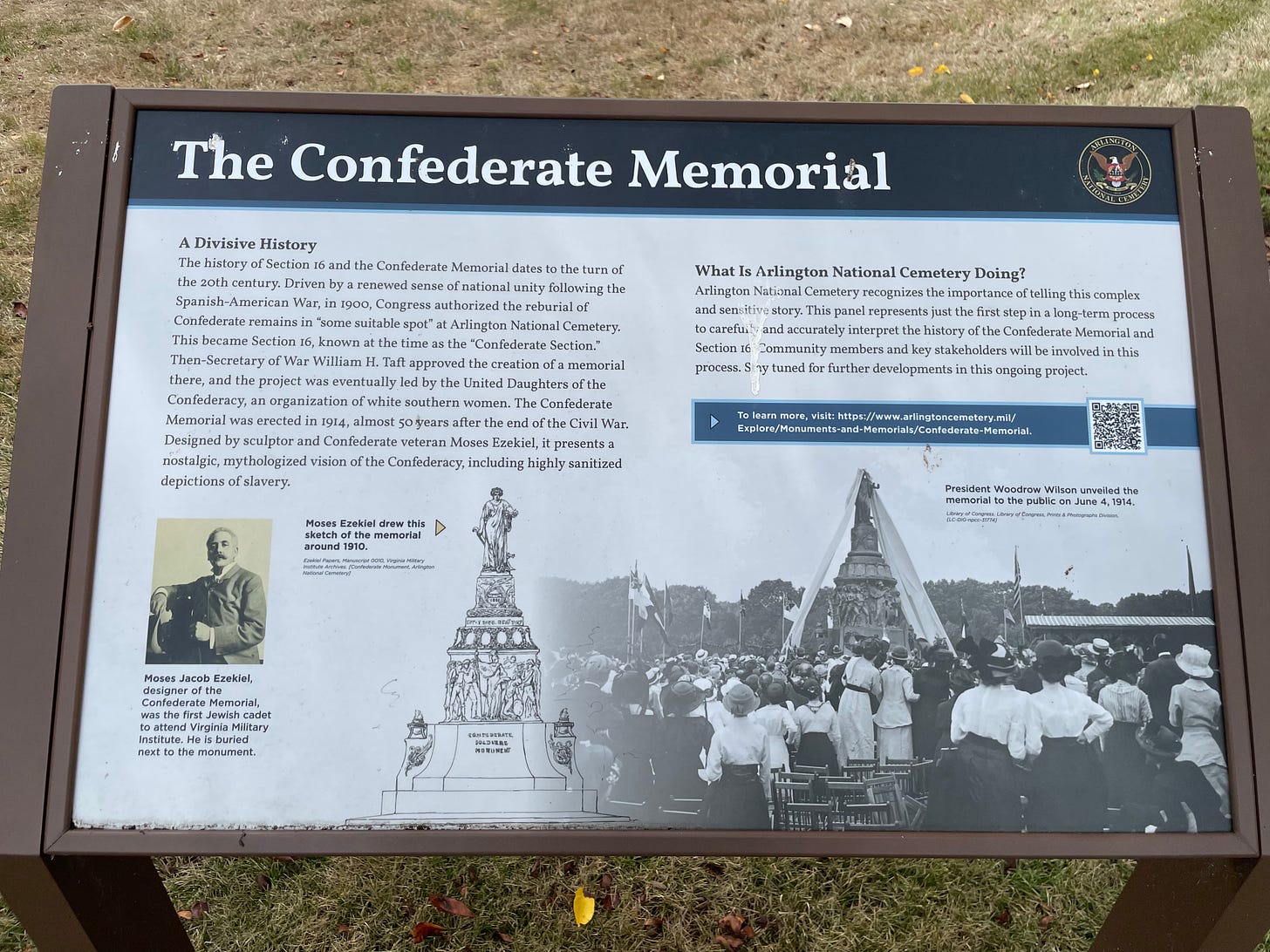

All that is left to remind visitors that a memorial once stood here is a wayside marker that was recently installed.

Though I only spent a few minutes in Section 16, one thing that I noticed is that the individual Confederate graves now speak more forcefully.

I am not someone who feels a need to condemn Confederate soldiers generally. Yes, I am glad that the Confederacy failed in its bid for independence and goal of creating an independent slaveholding republic, but I am a historian and student of history and there is much to learn from considering their individual stories and experiences. I’ve always been attracted to cemeteries, including Confederate cemeteries, for this very reason.

Without the memorial as a distraction, I found myself wondering through the section reading the headstones.

Let’s be clear. The Confederate monument dedicated in 1914 was never intended to simply honor the soldiers buried in Section 16. This memorial was never intended to be a symbol of reunion or reconciliation. It is an act of presentism to refer to this memorial, as many have done over the past few years, as a “Reconciliation Memorial.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy used this opportunity to celebrate the Confederacy and its Lost Cause. In the process the memorial distorts both the cause for which it fought and, in the process, claims African Americans as loyal stakeholders in the Confederacy’s quest for independence.

Any suggestion to the contrary suggests a willful act of ignorance.

Defenders of the memorial argued that the removal of the monument was a desecration of the graves, but that’s not what I sensed at all during my brief visit. Without the towering memorial hovering over Section 16 and the surrounding area, the Confederate graves—apart from their configuration—now recede into the broader landscape of individual graves.

Looking around it’s hard not to appreciate that the vast majority of individual service men and women lay in sections that have never stood in the shadow of any kind of monument or memorial. This has always been the case for the Union soldiers buried in Arlington and especially for the United States Colored Troops buried in the segregated and remote Section 27.

The names on the gravestones have always been sufficient in reminding visitors of their service and sacrifice.

I suspect that the vast majority of people who complained about the memorial’s removal have never visited Section 16 of Arlington National Cemetery and have no plans to ever do so. The debate was much more about our own political climate as opposed to anything having to do with history.

Regardless, the graves are still intact. Visitors are free to walk amongst the Confederate dead at their leisure to reflect, condemn or celebrate.

In that respect, nothing has changed.

Thank you for this insight. I’ll be at Arlington soon to attend an interment, and perhaps will visit some other sections as well.

Thanks for these thoughts, and amen to your emphasizing that the removed memorial "was never intended to be a symbol of reunion or reconciliation."

It reminded me of the fierce debate that took place over the course of several days last September in the Wall Street Journal. The argument started with an op-ed opposing removal of the explicitly Lost Cause monument from Jim Webb—Marine veteran with a Navy Cross, author of ten books, former secretary of the Navy, former Democratic senator from Virginia, and an enigma to me--a Virginian and former Navyman--for half a century. He blamed a “new world of woke” for the then-still-pending removal that he said would reveal “a deteriorating society willing to erase the generosity of its past, in favor of bitterness and misunderstanding conjured up by those who do not understand the history they seem bent on destroying.” Shezzam.

Three days of letters to the editor ensued. The online comment total reached about 3800. WSJ readers cared, and they generally echoed Webb’s cockamamie view that a monument—a public history statment—is ***itself*** history that can somehow be destroyed without first contriving a time machine for traveling back to do the destroying. Webb declared, falsely, that the 1914 monument’s “sole purpose” was “healing the wounds of the Civil War and restoring national harmony.”

Retired Brigadier General Ty Seidule, author of the first and longest letter, rejected that reconciliation argument. As others have pointed out in this forum, his _Robert E. Lee and Me_ traces his lifelong struggle to come to terms with the Civil War and slavery. His six-minute YouTube “Was the Civil War About Slavery?”—viewed by millions—demolishes Lost Cause sophistries.

A decade into his Army career, Seidule became a Ph.D. historian and West Point professor. Later he served as vice chair of the military base renaming commission that called for removing Arlington’s monument. “Reconciliation,” Seidule wrote, “didn’t include nine million African-Americans in the South who lived in a racial police state enforced by a terror campaign of lynching.”

Then: "Removing the monument doesn’t change history. It changes commemoration, which reflects our values. When the monument is gone, we can look to the empty space and say, finally, that the U.S. military no longer commemorates an enemy who chose treason to preserve slavery."

I'm glad Kevin, with his long memory of that thing, has now looked to that empty space and posted his thoughts.