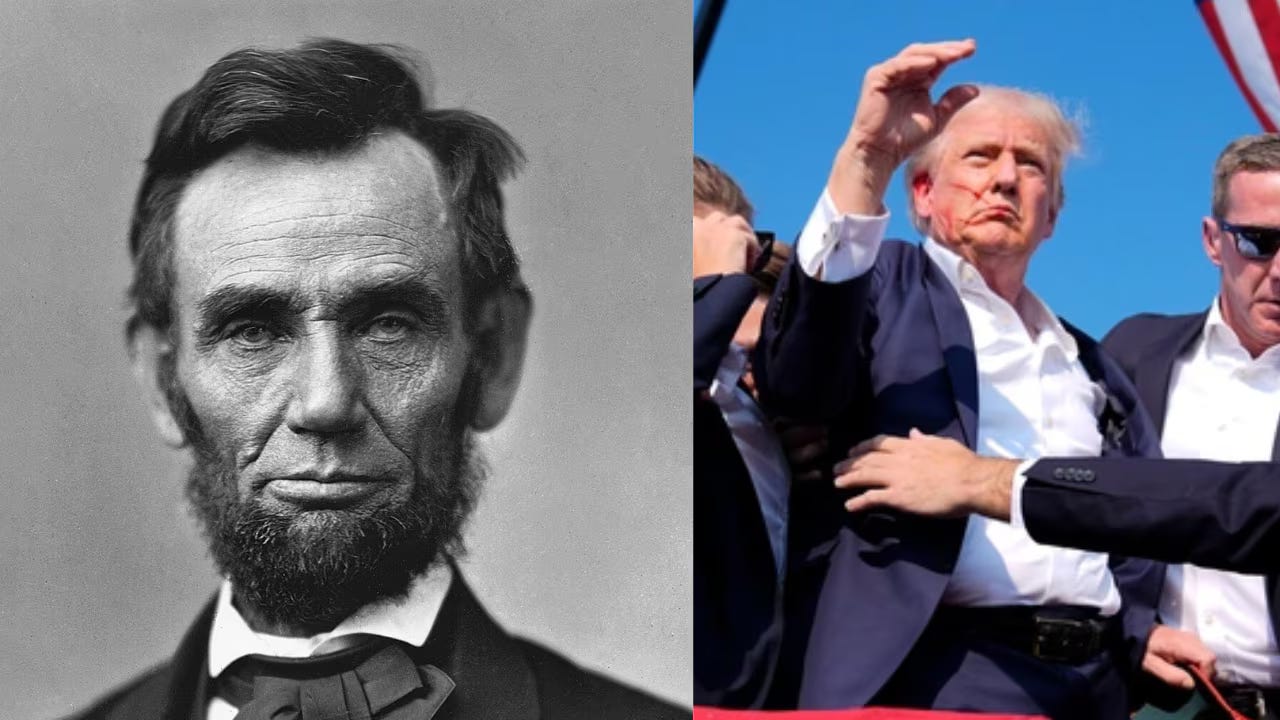

This morning I received an email asking me to comment on the recent attempted assassination of former president Donald Trump, its consequences and whether we are now closer to a civil war.

I certainly understand the need for insight at a time like this. Many people are experiencing a profound sense of uncertainty and fear about the present and future.

Yes, I study and write about a very violent period in American history that ended with the assassination of a president, but I have nothing to offer that might help to better understand our current crisis.

I am not throwing up my hands to admit failure as much as I am admitting my limitations as a historian and student of history.

As much as I look forward to opportunities to talk and write—sometimes in great depth—about the Civil War era, I’ve tended to resist the urge to offer guidance or lessons for the present.

Writing history takes time. It requires a willingness and even eagerness to hit brick walls along the way. Questions are posed only to be revised based on the availability of evidence and a host of other factors. Even at the end of the process, historians can expect that their interpretation will almost certainly come under criticism and be revised at some point by the next generation of scholars and writers.

This open-ended quality is what makes the study of history so exciting. Trying to attain a fixed interpretation of any aspect of the past is, as Peter Novick once suggested, kind of like “nailing jelly to the wall.”

In my mind, trying to apply the past to the present is even more difficult and fraught with problems.

I’ve grown weary of efforts to apply the lessons of the Civil War to our current political culture. There has been no shortage of op-eds predicting another Civil War over the past few years, but I tend to think that this commentary tells us more about the authors in question than anything helpful about the present or the past.

A number of historians that I deeply respect and have learned a great deal from over the years have attempted to compare the Lost Cause of the postwar South with Trump’s “Big Lie.” As I have said in previous posts, such comparisons make little sense to me.

Of course, historians have every right to comment on current politics or any other issue for that matter. We are, in the end like everyone else, citizens.

But keep in mind that such commentary is not necessarily informed by the methodology that goes into studying history.

Historians can provide context and remind us of what the nation has already experienced, but we have no privileged access to what we are currently going through or where this nation is headed.

To be honest, I am finding it very difficult to make sense of what has taken place over the past few days, weeks, months and even years. You might think that the solution is to soak up as much as possible from the many thoughtful writers and commentators that are out there, but I have moved in the opposite direction.

I am reading less across the board, especially on social media.

I don’t know what the consequences of this past weekend’s attempted assassination of Trump or of the outcome of the 2024 presidential election will be, regardless of who proves victorious. If history teaches us anything, perhaps it is that while we should remain vigilant, we should steer clear of the prediction game altogether.

Good luck and thanks for reading.

Thank you, Kevin, for a voice of reason. Steven, I, too, have a sense of dread.

Kevin, I think this is a very thoughtful and thought provoking essay. I think we are dealing with the consequences of our failure to deal with the consequences of the Civil War in the mid-19th century. But, I am not sure about the parallels between now and the Civil War period. Our time is put together by a different set of rules than theirs was. On the surface some appear similar but after reading Larson's "Demon of Unrest" I am convinced there are genuine differences between the Civil War period and now that we don't understand as well as we think we do. Despite this opinion I also think it is important for historians to continue to study this period confronting myths ( as you have done), and shading light on not well known events, and generally revising and reshaping the narrative of how we got where we are. That is the only way we will ever understand ourselves as a people, to paraphrase Lincon, warts and all.