I thought you might enjoy a little teaser for tomorrow evening’s special presentation (June 18 at 7PM EST) on the 160th anniversary of the assault on Battery Wagner by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The failed federal assault would cost the regiment dearly and include the loss of Shaw himself.

My presentation will include an overview of the assault and explore how the regiment and its colonel have been memorialized ever since. You will have the opportunity to ask questions and share your thoughts as well. This event is open to all paid subscribers, but there is still time to upgrade if you are interested and you can do so with this special discount offer.

I hope you can make it and I do appreciate your support. All paid subscribers will receive an email with a Zoom link for the presentation beforehand.

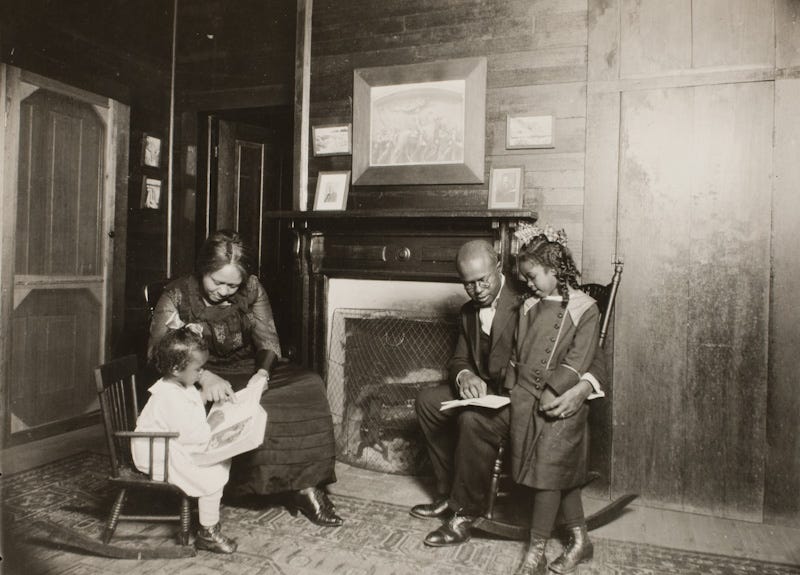

One of my favorite images that beautifully captures how Black Americans remembered Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts comes from the photographer Lewis Hine. I regularly used Hines’s photographs of underage child laborers when teaching the Progressive Era and Great Depression, but this particular photograph comes from a series he called “Southern Negroes” and is dated c. 1920.

The photograph beautifully captures a mother and father sitting with their children in front of a fireplace. Very few pieces of furniture are visible other than three chairs plus what looks to be a well-worn rug. The importance of education is front and center as both mother and father read to their two children.

Among the small number of framed photographs/illustrations on their walls is a print of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Shaw/54th Massachusetts Memorial. Prints of famous monuments were mass produced and authorized by sculptors like Saint-Gaudens, and especially Daniel Chester French, as a means to supplement their income. Boston publishers Curtis and Cameron issued 800 of these prints at different sizes beginning in 1898.

Hines’s photograph is a reminder of the importance that many Black families placed on celebrating and passing down an “emancipationist” memory of the Civil War—with an emphasis on Black military service—to the next generation.

The date of the photograph is also worth exploring. African Americans had volunteered in significant numbers during WWI at the urging of leaders like W.E.B. DuBois, who believed that military service might translate into civil rights and a recognition that they should be treated as full citizens. DuBois himself quickly learned, even before the Treaty of Paris was signed, that this was unlikely.

I can’t help but wonder if one of the framed images on the fireplace mantle is DuBois. Interestingly, the Niagara Movement (a predecessor to the NAACP), which DuBois helped to establish in 1905 used the Saint-Gaudens image on their shield.

At the organization’s annual meeting in Harpers Ferry, WV, DuBois referenced Robert Gould Shaw in a speech outlining their goals.

And we shall win. The past promised it; the present foretells it. Thank God for John Brown! Thank God for Garrison and Douglass! Sumner and Phillips, Nat Turner and Robert Gould Shaw, and all the hallowed dead who died for freedom! Thank God for all those today, few though their voices be, who have not forgotten the divine brotherhood of all men white and black, rich and poor, fortunate and unfortunate.

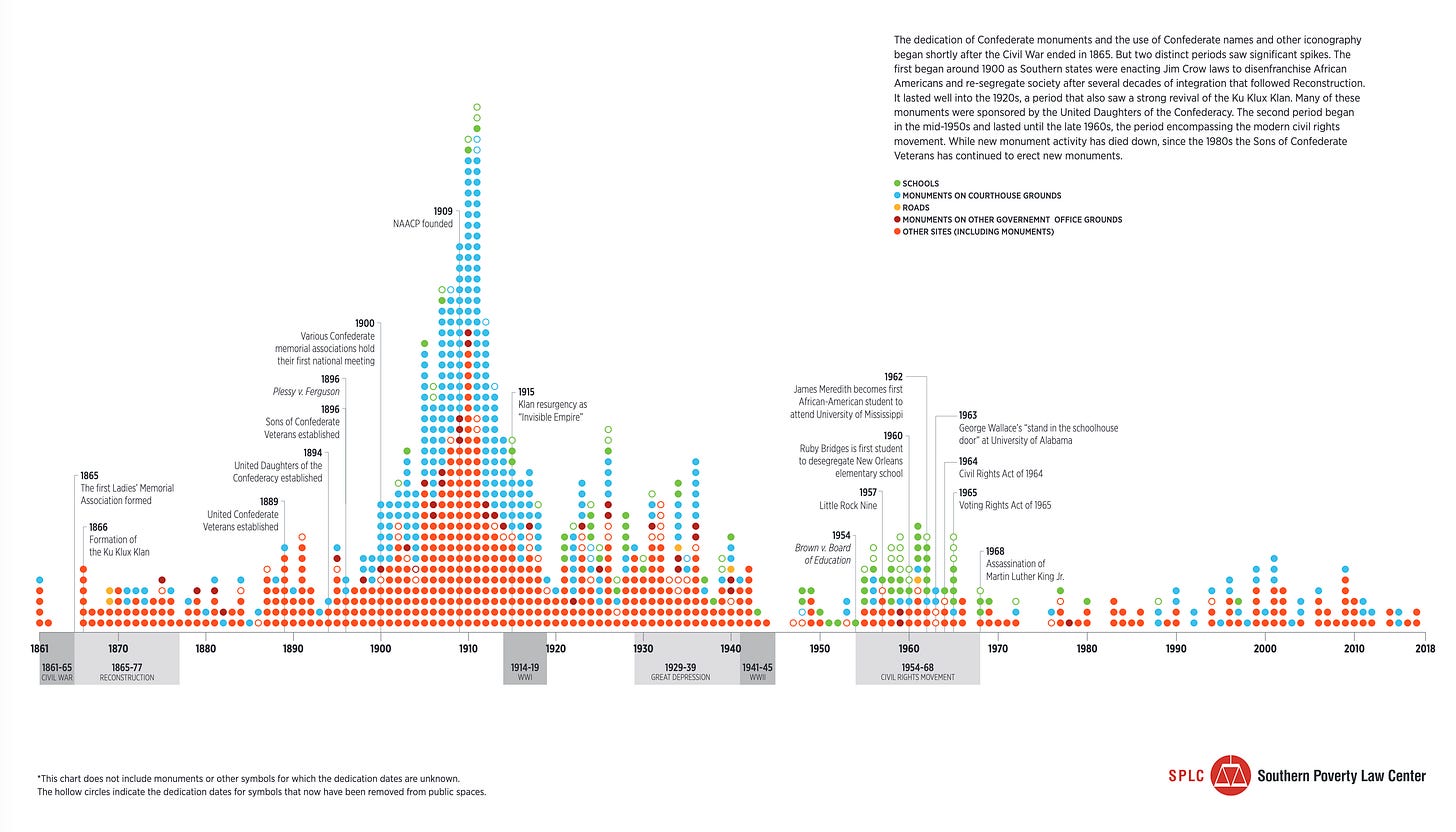

Memory of Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts continued to be a potent symbol for African Americans at the nadir of race relations in the early twentieth century. It also stood in sharp contrast with the hundreds of Confederate monuments that were dedicated during this period.

A number of these monuments directly challenged the memory of Black Union soldiers by depicting African Americans as “loyal slaves” during the war, including the Confederate monument in Arlington National Cemetery, which was dedicated in 1914.

If African Americans were encouraged by a memory of military service during the Civil War to continue to push for full civil rights and stand up against widespread violence then the image of the “faithful slave” was intended to remind white Americans of the necessity of maintaining legalized segregation and the racial status quo.

It would be interesting to know where Lewis Hine’s photograph of this Black family was taken, but regardless of location, it effectively captures one family’s commitment to a more promising future rooted in a courageous past.

Hi Kevin, will your presentation be recorded and available afterwards for any subscribers who cannot attend live? 7pm EST is midnight where I am!