Standing on the ground of Butler Island, just south of Darien, Georgia last week is something that I will not soon forget. There is simply no substitute to experiencing the landscape for yourself to begin to understand the scale of rice cultivation in the low country before the Civil War and the horrors of slavery.

In 1838, Pierce Mease Butler traveled to the plantation with his wife and British actress Fanny Kemble. She chronicled her time there and eventually divorced her husband, in part, over their disagreements about slavery.

But as much as I savoured the moment on site, the lack of any serious interpretation left me wanting more. As I drove further south to Simons Island I decided to stop off at Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation, which is operated by the state of Georgia. Like Butler Plantation, this site also sits along the Altamaha River. The plantation was built in 1807 as a large rice producer with over seven thousand acres of land and more than 350 West African slaves, mostly from Senegal and Sierre Leone.

I had high hopes as I walked into the visitor center. The short film had some serious problems, but the exhibits offered a pretty good overview of operations on the plantation. The book selection was also surprisingly good. I picked up a copy of Mart A. Stewart’s book, What Nature Suffers to Groe: Life, Labor, and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1680-1920.

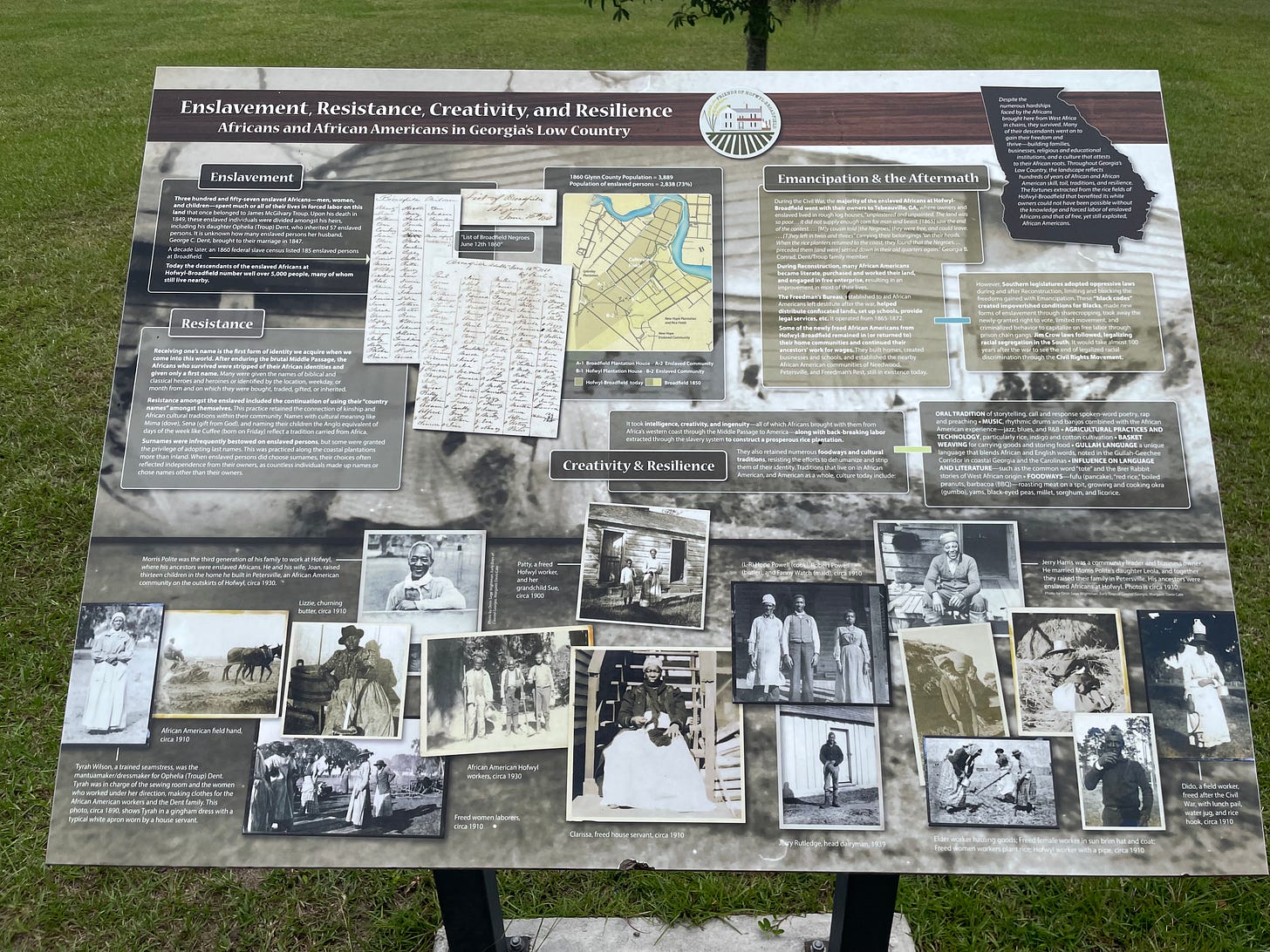

As I emerged from a beautiful path, lined with live oaks, dripping with spanish moss, I came upon an interpretive marker that focused on the lives of the enslaved.

Then I entered the house.

I was greeted by an elderly white woman, who in a matter of five minutes undercut everything that I had assumed about how the staff interprets the history of slavery at Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation.

The first thing I noticed was the photograph of an elderly Black man on a table in the entryway, who I learned continued to live on the plantation well after the Civil War and emancipation. He was one of landowner George Dent’s 357 “loyal” slaves. Yes, she actually used that word.

I pushed back as much as I could, but I quickly realized that it wouldn’t do any good. In response to one of my questions she suggested that we need to appreciate that ‘times were different.’ In a hundred years Americans will look back on our generation and wonder how we could have allowed for the ‘murder of unborn millions.’

There was no serious attempt to understand the lives of the hundreds of enslaved who lived, worked, and died on this plantation. It felt as if I had stepped back decades, which was confirmed when I learned that my guide had worked in the home for over 30 years.

Here we were in a home overlooking thousands of acres of land and marshes that demanded backbreaking work and countless long hours to produce the wealth responsible for this home and every object in it and according to my guide the enslaved were content and loyal.

My visits to Butler Island and Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation made me appreciate the recent push to revise our language when talking about these sites. Perhaps we should refer to them as ‘forced’ or ‘slave labor camps.’

In that moment I wanted to scream. I left feeling frustrated and angry.

Let me be clear, however, that I wasn’t so much upset with my guide as I was with the management of this site.

The next day, while on James Island, just south of Charleston, I decided to visit McLeod Plantation Historic Site. I’ve heard some wonderful things about how they interpret the live of the enslaved. I ended up on the first tour of the day. Our guide’s name was Ista and within a few minutes I realized that I was in good hands.

One of the first things that Ista made clear is that the tour would not include the house. We could explore the building after the tour, but this was going to focus entirely on the lives of the enslaved.

He prefaced our walk by discussing the Lost Cause myth and how it has shaped our memory of slavery. The beautiful tree-lined path connecting the home to the road, he explained dates to the turn of the twentieth century, a time when northerners traveled south looking for the “Old South.”

I asked him if there has been a discussion about the language used to refer to McLeod. Ista referred to it as a plantation. He was quick to respond that he could easily utilize the new language (referenced above) but Ista made it clear that this language runs the risk of alienating certain visitors. Why take that risk, he explained, when all of the important points can be made by continuing to use a more familiar language.

That makes perfect sense to me.

For the next hour Ista shared the stories of the men, women, and children who lived at McLeod. He left out nothing and censored nothing. We explored the lives that the enslaved attempted to build and the violence and coercion that lay at the center of the master-slave relationship.

Ista told stories of how families were separated and the evidence of rape as well. He explained how sea island cotton is cultivated overlooking just a small portion of the vast McLeod landholdings.

A small number of slave cabins have survived. The McLeod family owned the property until 1990 and the cabins were still occupied as recently as the 1970s, which I find both fascinating and horrifying.

I decided not to visit the McLeod home. What was I going to see that I haven’t already seen at any number of other plantation homes? No, this tour was going to be devoted entirely to the lives of the enslaved and perhaps intended also as a silent protest to what I had witnessed the day before.

Let me be clear. Much as changed in how plantation sites are interpreted, but this experience reminded me that we still have a long way to go. The important point is to do your research beforehand before visiting one of these sites.

A sad but not surprising story regarding your visit to Hofwyl-Broadfield. It's distressing that there are places that still insist on not telling truths about their plantations. Some interesting notes about people once enslaved there can be found here. http://www.glynngen.com/enslavement/IAmHofwyl.html

I will say one of the things that I find desperately lacking still in these separated tours is that slavery existed in the mansion houses and yards of those spaces. Enslaved maids, butlers, carriage drivers, nurses, midwives, gardeners, and valets had lives dominated by work in these spaces. Yet, too often it's "The slavery tour" as though we should not be having these discussions on *EVERY* tour for those folks as well as those who lives were dominated by field labor (which is skilled) or other skilled labor. I find this to be the case, still, in many historic sites with slavery history.

Your account strikes several cords; I have long thought we should describe these places as industrial farms operated with slave labor. That is one aspect of British colonialism that differs from other European countries. Almost everywhere they went, but especially in the Americas, the British established these large industrial farms and worked them with slave labor. This obviously did not happen every where (ie. Canada and the middle and New England colonies). There are a variety of reasons for the British went down this industrial farm road that are too complicated to get into here but the farms shaped the colonial and post-colonial periods no matter where they existed. The other cord is the degree, it appears to me especially in South Carolina, to which southerners go to hide slavery. I was in Charleston a few years ago and spent time exploring the old town area. I have never seen so many National Register of Historic Places medallions. But what was interesting is in most of these houses what had been the domestic slave quarters was either hidden from public view or gone. The public of today did not have to see this negative part of local history. Also the slave market was in a remarkably plain looking building that, based on period photographs, did not identify its role. And even now, unless you were really looking for it you would miss it. What also struck me was that many of the houses, in Charleston, were city residences for families that had what I took to be large country places. The city places would I assume have presented a sanitized aspect of life for the owning families whose wealth rested on the labor going on int he country places. Today the city places present a sanitized version of souther history more like what you appear to have encountered at the first location you visited.