The decision to begin recruiting African Americans into the United States Army in 1863 was a watershed moment for the nation. Few people could have anticipated such a development in 1861 and fewer people supported the policy. The rush on the part of African Americans to prove their manhood and claim a place as citizens in a reunited nation unleashed a backlash that echoed Roger Taney’s infamous Dred Scott ruling in 1857 that free and enslaved Blacks, “were not and could never become citizens of the United States.”

Roughly 200,000 Black Americans helped to reunite the nation in 1865 and bring freedom to four million people as a result of their military service. It was a revolutionary moment for the nation—one whose legacy we are still struggling to come to terms with all these years alter.

We often forget that both the United States and the Confederacy refused to recruit Black men into their respective armies in 1861. The policies of both nations reflected, in part, a deep seated racism and skepticism about the ability of Black men to fight and the fear of what it might lead to as a result. The United States attempted to save the Union without disrupting the institution of slavery while the Confederacy fought specifically to save its “peculiar institution.”

The Confederacy faced a similar watershed moment when its government authorized the enlistment of Black men as soldiers in March 1865. Unfortunately, this moment in the history of the Confederacy has long been obscured by the myth that Black men had been fighting as soldiers in numbers ranging anywhere from 500 to 100,000 throughout the conflict. The preoccupation with so-called Black Confederates and the attempt to get the Confederacy ‘right on slavery’ moves us further from truly appreciating the reaction and potential revolutionary impact of this policy on the Confederacy’s future.

Earlier this week my friends at the Georgia Historical Society shared with me a remarkable document that offers a tiny window into the significance of the Confederacy’s slave enlistment policy.

As many of you know from reading Searching for Black Confederates, the Confederacy engaged in a very public debate throughout much of 1864 and early 1865 over the question of whether to enlist slaves as soldiers. This debate unfolded in hundreds of editorials in newspapers across the Confederacy, the speeches of politicians in Richmond who debated the issue, and the letters and diaries from those serving in the army. Entire regiments voted on the question and published the results in newspapers.

As I have pointed out on numerous occasions, not once did someone—regardless of their position on slave enlistment—point out that Blacks were already serving as soldiers. The Confederate populace understood that this would be a step in a radically new direction.

The policy that was approved on March 13, 1865 tasked individual regiments with the responsibility of recruiting Black men, who had already been freed by their masters. These men were to be integrated into already existing units rather than organized as separate all-Black regiments as was the case in the United States.

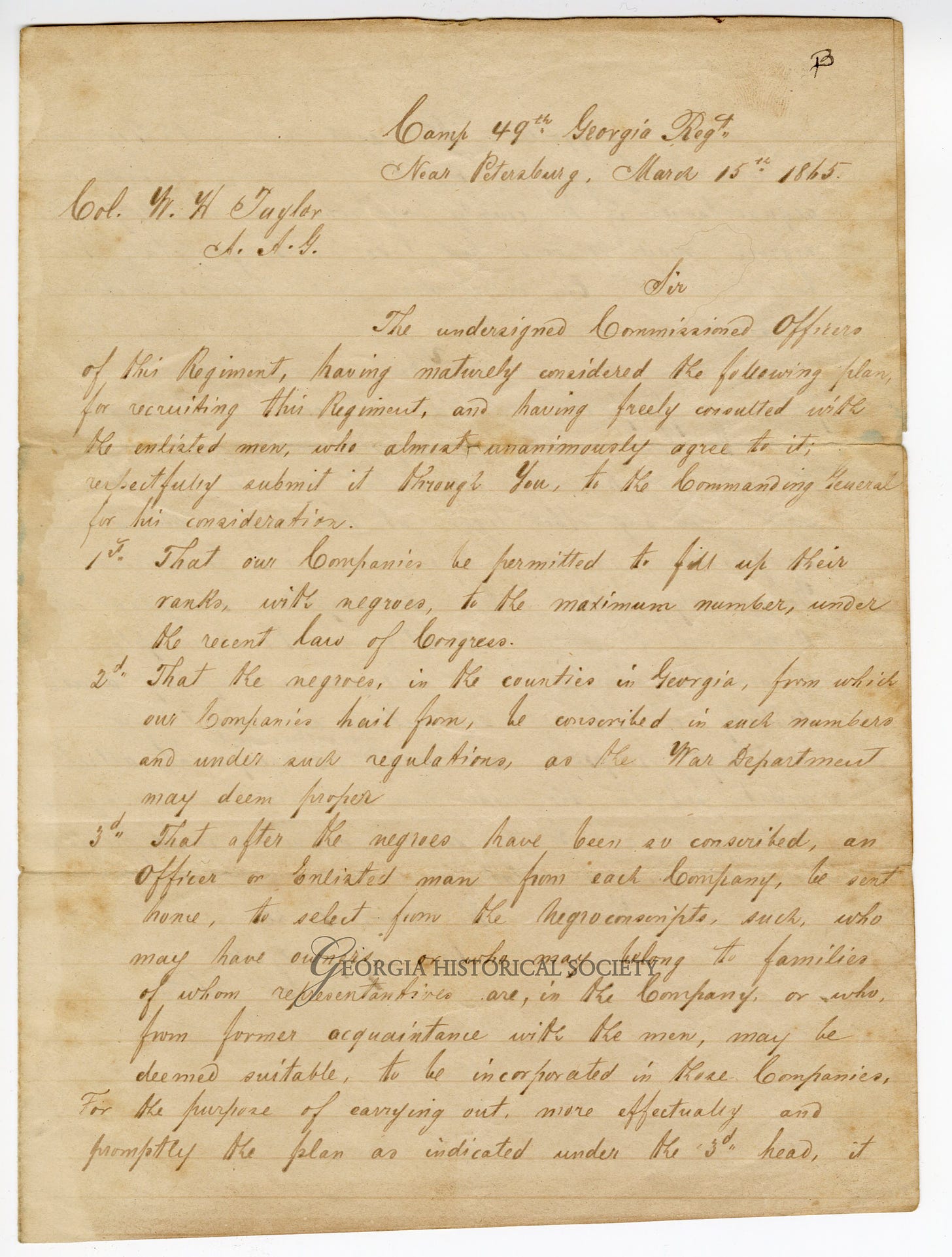

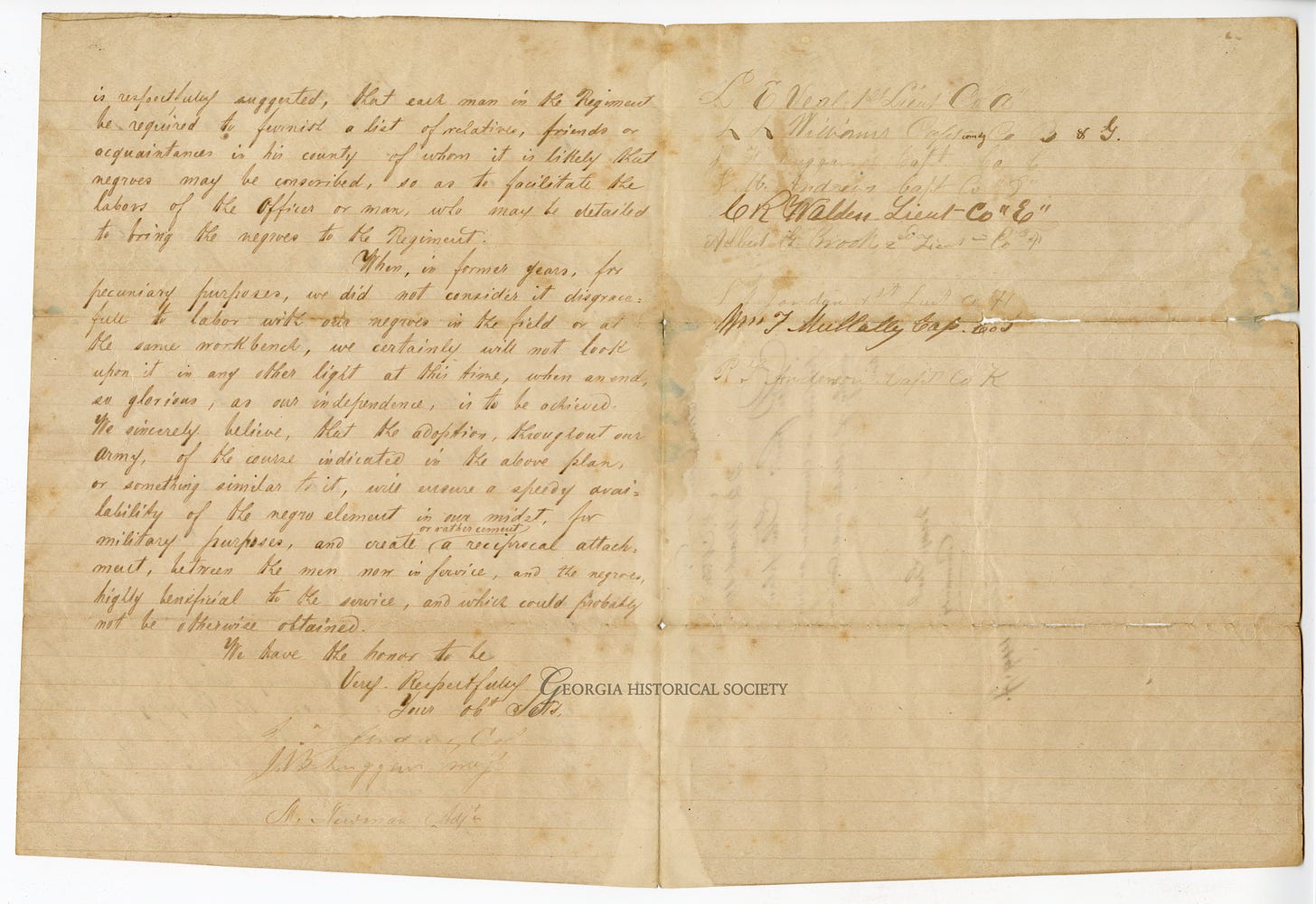

Just two days after the policy was approved, the officers of the 49th Georgia Infantry requested authorization through General Robert E. Lee’s staff, “to fill up their ranks, with negroes.” Officers in other regiments in the Army of Northern Virginia did the same.

The document itself is significant. The formal language makes it difficult to appreciate the radical shift in the relationship between Black men and the military that this new policy inaugurated. For the first time regiments acknowledged Black men not as laborers or as slaves, but as soldiers.

The officers of the regiment clearly hoped that anyone assigned to enlistment duties back home would, “select from the negro conscripts, such who may have owners or who may belong to families of whom representatives are, in the Company, or who from former acquaintances with the men, may be deemed suitable to be incorporated in these Companies.”

The concern here was not simply finding men who were physically prepared to take on the challenges of military life. Confederate conscription policies were already scraping the bottom of the barrel of its white population. What they appear to be concerned about is locating Black men who were known not to cause problems or unrest in their respective communities, regardless of their legal status.

The final paragraph is fascinating and worth reading in its entirety. It is a reminder that most slaveowners in the South owned relatively few slaves and often found themselves working side-by-side with the enslaved to complete tasks in the fields and other settings. Of course, what is ignored entirely is the legal distinction that defined the lives of the enslaved and white southerners. Instead, the officers of the 48th Georgia envisioned Black and white men engaged in the shared labor of winning a war that would ultimately protect the institution of slavery.

They not only anticipated that Black men would volunteer in large numbers, but that “a speedy availability of the negro element in our midst, for military purposes” would “create or rather cement a reciprocal attachment between the men now in service and the negroes.”

One of the radical elements of this document is in the way it nudges both the men in the ranks and especially those on the home front to begin to fundamentally rethink the relationship between Black and white southerners. It’s important to keep in mind that no one at the time had any idea of the potential short- or long-term implications of this policy and how long the war would continue.

We should be skeptical that the enlistment of slaves would have significantly reordered southern society. Historian Bruce Levine has argued convincingly that the Confederacy’s slavery enlistment plan was, in part, an attempt to save slavery even as it pushed Black men into the ranks to help achieve its independence. This was not a general emancipation policy.

That said, it is worth considering whether the presence of Black men in Confederate ranks, as part of an extended conflict, would have resulted in a lasting respect and attachment that transcended race.

Barbara Gannon’s groundbreaking research on Black and white Union veterans is worth considering. She makes the case in The Won Cause that strong bonds of affection remained strong among these veterans in integrated Grand Army of the Republic camps throughout the country during the postwar era—one of the few settings in which you could find such close interracial cooperation in Gilded-Age America.

We will never know just how revolutionary the Confederacy’s slave enlistment policy might have been given its surrender just weeks later. Only a handful of former slaves were enlisted in Richmond and there is no evidence that they ever saw the battlefield.

In the end, the timing of this potentially radical new direction reflected the Confederacy’s committment to not disturbing its “cornerstone” of slavery and white supremacy.

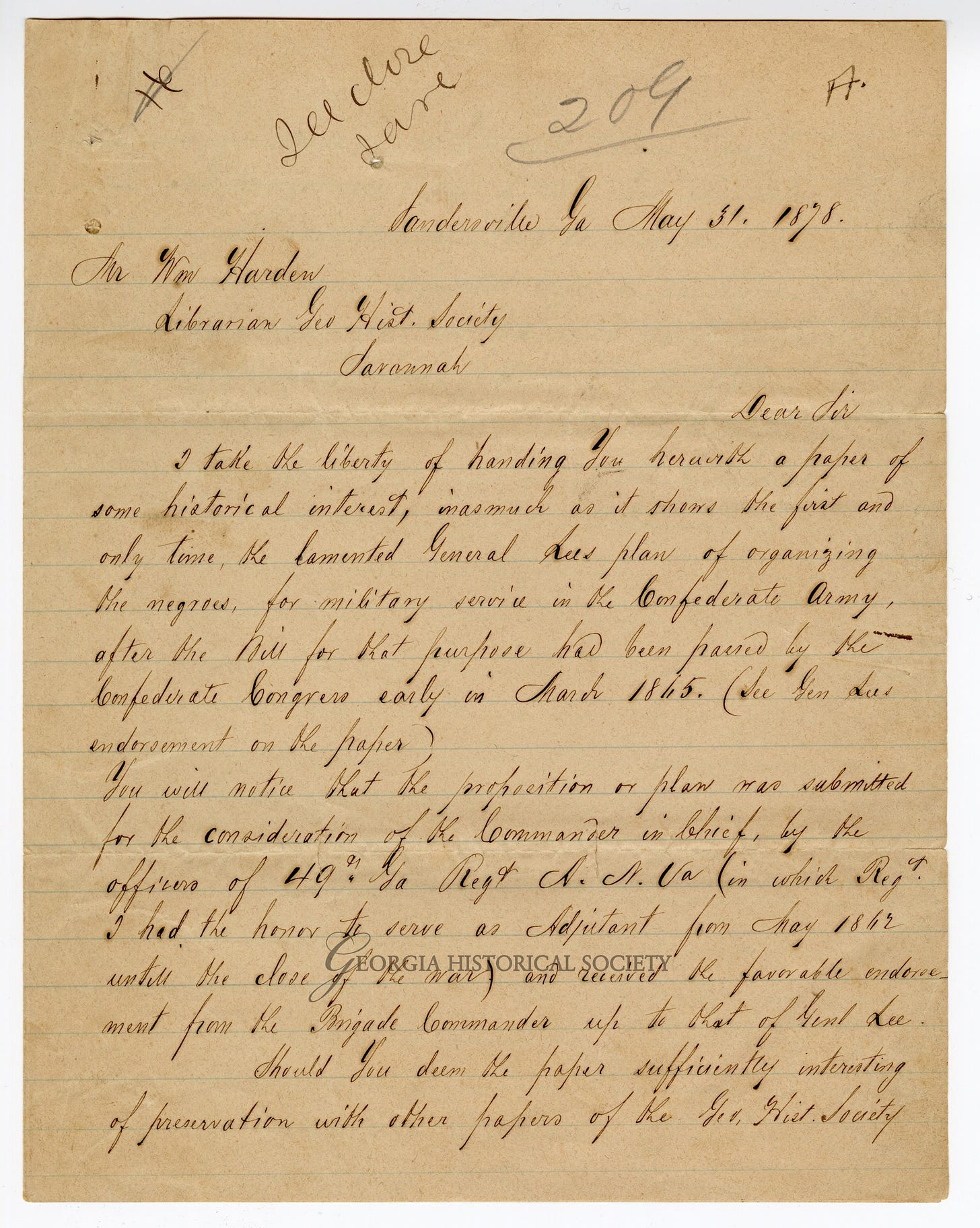

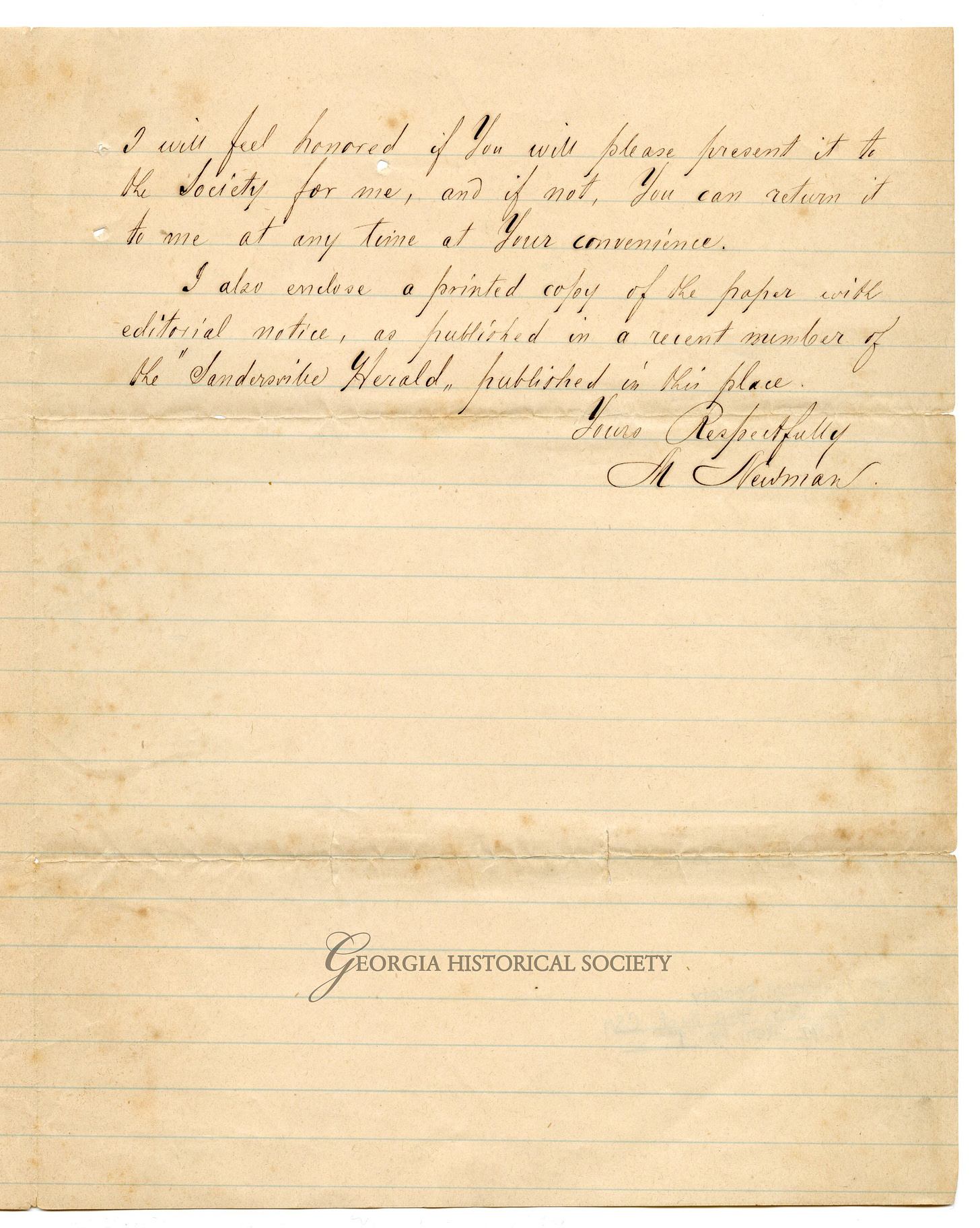

In 1878, Mark Newman, who served in the 49th Georgia, inquired as to whether the Georgia Historical Society was interested in adding these documents to its collection. Newman understood the significance of these documents in pointing out that they represented, “the first and only time, the lamented General Lee’s plan of organizing the negroes for mlitary service in the Confederate Army…had been passed by the Confederate Congress early in March 1865.”

There was no confusion in Newman’s mind or anyone else for that matter as to the nature of the shift in the relationship between Black men and the Confederate military that was signaled in this new policy. He was not seduced by stories of thousands of brave and loyal Black soldiers fighting for the Confederacy.

Mark Newman was there.

Over the years I’ve been accused of ‘disrespecting’ and ‘dishonoring’ the memory of Confederate soldiers in my ongoing attempt to debunk the Black Confederate narrative, but our goal should and must be to respect and honor the historical record to the best of our ability.

Only through respecting and acknowledging the historical record will we have any chance of fully appreciating the significance of the Confederacy’s decision to enlist slaves into its military as soldiers and for the men in the 49th Georgia who approved it.

Great point, that nobody promoting black recruitment referred to any African Americans already serving as Confederate soldiers. I learned a lot from Levine’s book, as well as yours, but Gannon’s also sounds very useful.

Many thanks for introducing me to this fascinating document. It and your commentary add a new depth to the issue.