A Reminder of "The Great Task Remaining Before Us"

A few thoughts on this 162nd anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's "Gettysburg Address."

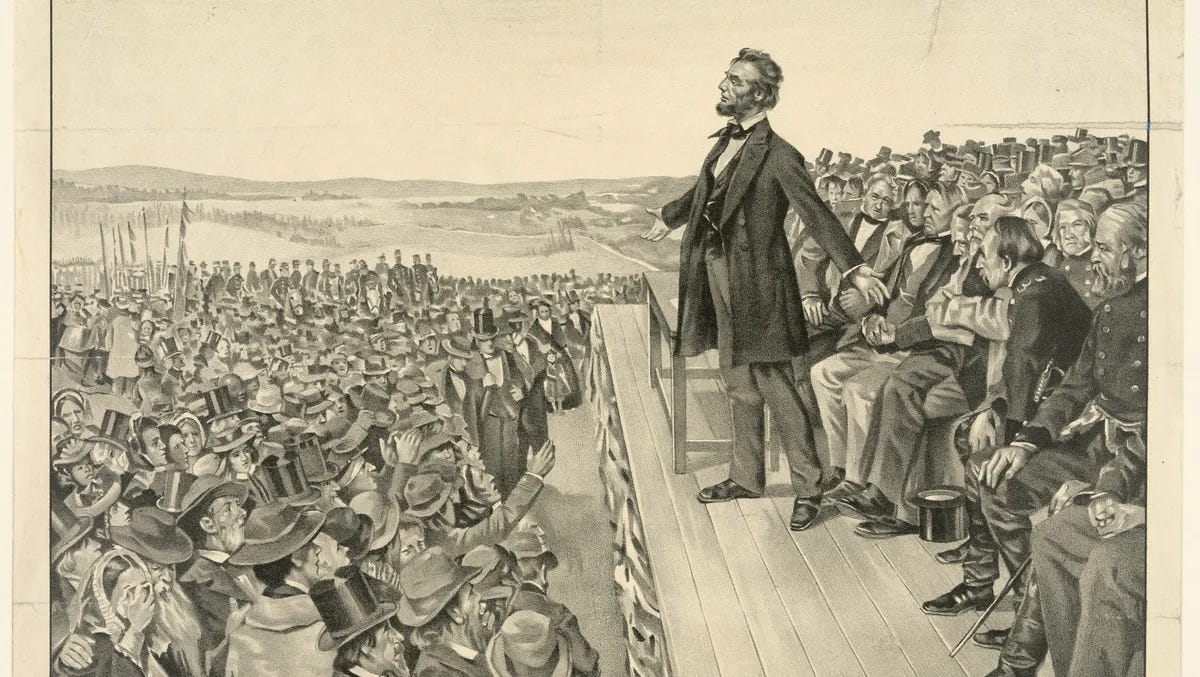

Though today it is regarded as one of the greatest expressions of American political thought, Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”—delivered on this day in 1863—was not immediately regarded as such. Contemporary newspaper reactions reveal a landscape of sharply divided opinion shaped by politics, sectional identity, and wartime emotion.

Many Republican-aligned newspapers recognized the significance of Lincoln’s speech from the outset. Their praise often centered on the Address’s brevity, emotional power, and philosophical depth.

For example, the Chicago Tribune applauded the speech as “the dedicatory remarks by President Lincoln, which will live among the annals of man” and specifically called it “a perfect gem” The paper contrasted Lincoln’s efficient eloquence with the longer oration by Edward Everett, remarking that the President had expressed “the whole matter in two minutes” while Everett required hours.

Similarly, the Providence Daily Journal described the Address as “models of brevity, clarity and force” and noted that its sentiment was “deeply felt by all present” Other supportive papers echoed this sentiment, seeing the speech as an articulation of the Union cause’s moral purpose.

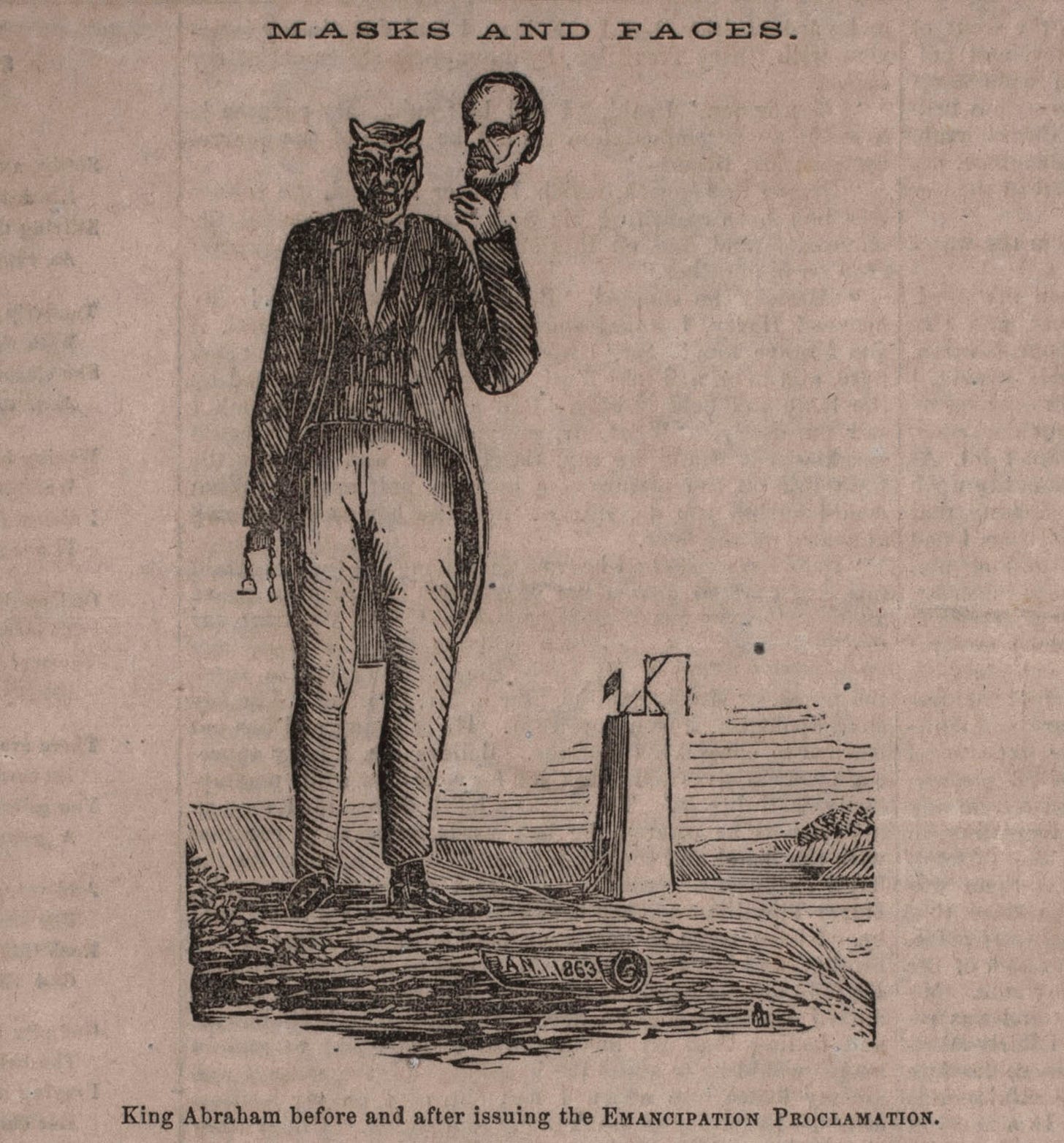

On the other hand, Democratic newspapers—opponents of Lincoln and critics of the war—were dismissive or openly hostile. The most widely cited example comes from the Chicago Times, a strongly anti-Lincoln Democratic paper. Its editorial attacked the speech in strikingly harsh terms: “The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat, and dishwatery utterances of the man who has to be pointed out as the President of the United States.”

The paper also condemned Lincoln for supposedly insulting the war dead, arguing: “We pass over the silly remarks of the President. For the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of.”

The Cincinnati Enquirer printed similarly negative coverage, asserting that Lincoln’s speech was “a perversion of history so flagrant that the most brazen of partisans must blush.” Other Democratic outlets criticized the speech’s brevity, interpreting it as evidence “of Lincoln’s inadequacy.”

Not surprisingly, newspapers in the Confederacy reacted with scorn, sometimes mocking the event itself rather than analyzing the speech.

The Richmond Examiner ridiculed Lincoln personally, calling him “the fungous growth of Republicanism” and referring to the ceremony as “the ludicrous pageant at Gettysburg” Although it did not reprint the Address, its dismissive tone reflected a clear attempt to maintain and encourage support for the Confederate war effort in the wake of two major battlefield defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg.

The Charleston Mercury characterized the Gettysburg ceremony as “Yankee buffoonery” and called Lincoln’s remarks “the utterances of a feeble mind.” Southern papers viewed Lincoln’s speech through the lens of wartime hatred and rejected any notion that the Union had the moral authority to consecrate the battlefield.

One of the most important contemporary reactions came not from the press but from Edward Everett, the renowned orator who delivered the main speech at Gettysburg.

In a letter to Lincoln dated November 20, 1863, Everett famously wrote: “I should be glad if I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.” Everett’s praise, later reprinted in papers such as the New York Times, offered early, influential recognition of the Address’s brilliance, even as partisan papers disputed its value.

The decisive factor in transforming the Gettysburg Address into a national touchstone was its adoption into public school curricula. Beginning in the 1890s, as national identity was reshaped in response to industrialization, immigration, and an evolving Civil War memory that placed greater emphasis on reunion, educators sought concise, uplifting texts to teach American democratic ideals.

By the early twentieth century the address appeared in nearly every major American school reader. Students memorized it routinely, often alongside the Declaration of Independence and it was recited at school ceremonies, Lincoln’s Birthday observances, and civic events.

This educational institutionalization ensured that generations of Americans learned, repeated, and internalized Lincoln’s words from childhood. The speech’s rhetorical and moral power, now universalized through schooling, became part of everyday American civic life.

The dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922 dramatically accelerated the Address’s elevation in the nation’s collective memory and in civic culture. The text was carved on the interior walls of the memorial, giving it the form of national scripture. Millions of annual visitors read the speech as part of a pilgrimage to the symbolic heart of the republic.

During the mid-20th century, as the U.S. fought World War II and later confronted the Cold War, the Address was invoked as a statement of universal democratic values. American presidents, civil rights leaders, and veterans’ organizations routinely quoted it. Its vision of a “new birth of freedom” and “government of the people, by the people, for the people” resonated with national ideological commitments in an era of global conflict.

Throughout the civil rights era the speech was referenced as a universal declaration of equality.

The speech has withstood the test of time because it embodies the ideals that so many of us cherish and believe still bind us together as a nation. Take the time to read it again as a reminder of our collective aspirations and promise for a better future.

November 19, 1863

Gettysburg, PA

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us,that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion, that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

For further reading:

Martin P. Johnson, Writing the Gettysburg Address (University Press of Kansas, 2013).

Jared Peatman, The Long Shadow of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (Southern Illinois University Press, 2013).

A well written piece that provides context for the Gettysburg Address. My wife and I visit the Lincoln Memorial each time we are in DC to once again read the address and reflect upon it as American citizens. Our country is now in a turmoil where history is being used for propaganda purposes.

I think there is such a thing as American exceptionalism, but it is not as we usually think of it. American exceptionalism is laid out in the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln's Second Inaugural and the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution, and the 14 points and the four freedoms speech and the Letter from the Birmingham Jail and other writings I've left out. As some else said all Americans should read the Lincoln documents and I will add the others regularly. Unfortunately, only historians do and we are not as skilled as we ought to be at conveying the meaning to out countrypersons