A reader asked for more information about the image that accompanied my last post. It is titled “News From Home” and was sketched by the artist Edwin Forbes. The scene is a Union soldier reading a letter from home (or perhaps a newspaper), in camp, near Culpepper [sic] Court House, Virginia and was sketched on September 30, 1863.

I absolutely love the visual culture produced during the Civil War, especially the sketches of Forbes and Alfred Waud.

Both artists covered every aspect of the war, from life in camp to blood-soaked battlefields covered in dead bodies. Published in countless newspapers across the country, they brought the war home for a civilian population desperate for news from the front and any information they could glean about the well being of family members and friends.

This particular sketch of a Union soldier has always captured my imagination. It highlights a moment in the life of this individual. The soldier is lost in thought and doesn’t appear to be aware that he is even being sketched. In many ways, he embodies the idea of the citizen-soldier, who was willing to put aside his own pursuits as well as his family and risk his life for the sake of the Union. If he was lucky enough to survive the war, he would return home and pick up where he left off.

The sketch raises many questions: If he is reading a letter from home, how long had he waited for this latest letter? How is his family doing without his presence back home? What, if any, impact did this letter have on him moving forward?

If it is a newspaper, what’s the latest information on the political front (perhaps a hint at the next year’s presidential election) as well as other military operations beyond Virginia?

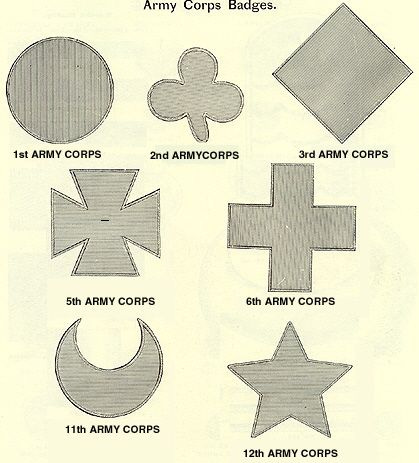

Unfortunately, I am unable to make out the corp designation badge located on the soldier’s kepi. General Joseph Hooker introduced corps badges to the Army of the Potomac after taking command in early 1863 following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg. They were intended to instill unit pride and improve morale.

But even without a reference to a specific corps, we can begin to approach what this individual may have experienced in recent months.

The previous May this soldier likely fought in the battle of Chancellorsville, not far from where this scene was sketched. Confederate victory led Robert E. Lee to bring his Army of Northern Virginia north into Pennsylvania, where they fought at Gettysburg in early July. A decisive victory forced Lee south, but by the middle of the summer the two armies were positioned roughly back where they had started in central Virginia in and around Culpeper.

In short, this soldier had likely participated in two major battles, marched hundreds of miles and ended up right back where he started.

How much of the fighting between these two battles did this soldier witness? How many friends did he lose? What experiences would he carry with him for the rest of his life?

We know a great deal about the experiences of Civil War soldiers. There is a deep body of scholarship that covers the entire arc of a soldier’s life from enlistment to his twilight years as a veteran. Many of these studies explore various themes by mining hundreds of soldier accounts.

We can learn a great deal from this approach, but Edwin Forbes’s sketch of this individual is a reminder that no one moment captured the experience of soldierhood.

As historian Peter Carmichael has argued, “The whirlwind of conflicting obligations of military life reminds us that a ‘soldier’ was never as state of being but alway a process of becoming.” We must consider the “totality of the Civil War military experince—the idealism, the camaraderie, the boredom, the marching, the singing, the sickness, the stink, the filth, the drilling, the punishments, the hunger, the exhaustion, the frustrations of being away from their families, the mental fatigue, and the grinding poverty that caused men to forget who they were, what they looked like, and even what they used to be—all punctuated by the horrible violence that in an instant turned beloved comrades into unrecognizable corpses.” (p. 11)

Forbes’s quiet and contemplative soldier carried all of this with him.

There is a sense in which I prefer the many sketch artist renderings to the photographs and paintings. One of my favorites, reflecting my interest in Grant, is a drawing of him whittling in the Wilderness. My copy was given to me by Emory Thomas, 30+ years ago. [I tried to post a copy here, but the app doesn't let me. 😒)

Thank you for telling us more about this sketch. I grew up in Culpeper and the war washed back and forth across it many time. I was telling some fifth graders about the Battle of Brandy Station once, and they were so engrossed, a young man asked, “Did you see any dead bodies, Mrs. Crockett?!” :-) The book * Seasons of War: The Ordeal of the Confederate Community, 1861-1865* c1995 by Daniel E. Sutherland, covers the war as it affected Culpeper. Halfway between Washington and Richmond, Culpeper was always in the way.

And regarding the spelling “Culpepper” our school district once had to send new school busses back to correct the spelling. :-D