It’s hard to believe that before President Biden signed a bill declaring Juneteenth a federal holiday last year, the United States did not officially commemorate the end of chattel slavery in 1865. Perhaps this should come as no surprise in a nation that has long distorted, mythologized and ignored this history. The ongoing debate about history education suggests that we are still struggling to come to terms with the history and legacy of slavery and white supremacy in the United States.

This new federal holiday is a small step, but it is a step nevertheless. Unfortunately, I suspect that most Americans will learn very little, if anything, about this new holiday and what they do pick up will be an overly simplistic and even distorted historical picture.

Most people will pick up little more than the fact that on June 19, 1865 General Gordon Granger released General Order No. 3 proclaiming freedom for enslaved people in Texas:

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

The image is of enslaved people waiting to be told that they were free in remote Texas, months after the end of military action and the assassination of President Lincoln back East.

There is a danger in commemorating Juneteenth as just another moment in a white savior narrative—one that views General Granger as a minor “Great Emancipator” type figure.

The problem is that depicts enslaved people as disinterested in their own freedom, but more importantly, it obscrues the pivotal role they played in the story of emancipation and the end of slavery between 1861 and 1865.

Enslaved people were not detached observers waiting to be freed. Across the Confederacy, as well as the Border States, enslaved people helped to push military policy in their favor in myriad ways and the nation toward emancipation.

They ran away from their plantations seeking refuge and freedom among the United States military. Their initiative forced military and political leaders to begin to craft policy regarding their status beginning in the first months of the war.

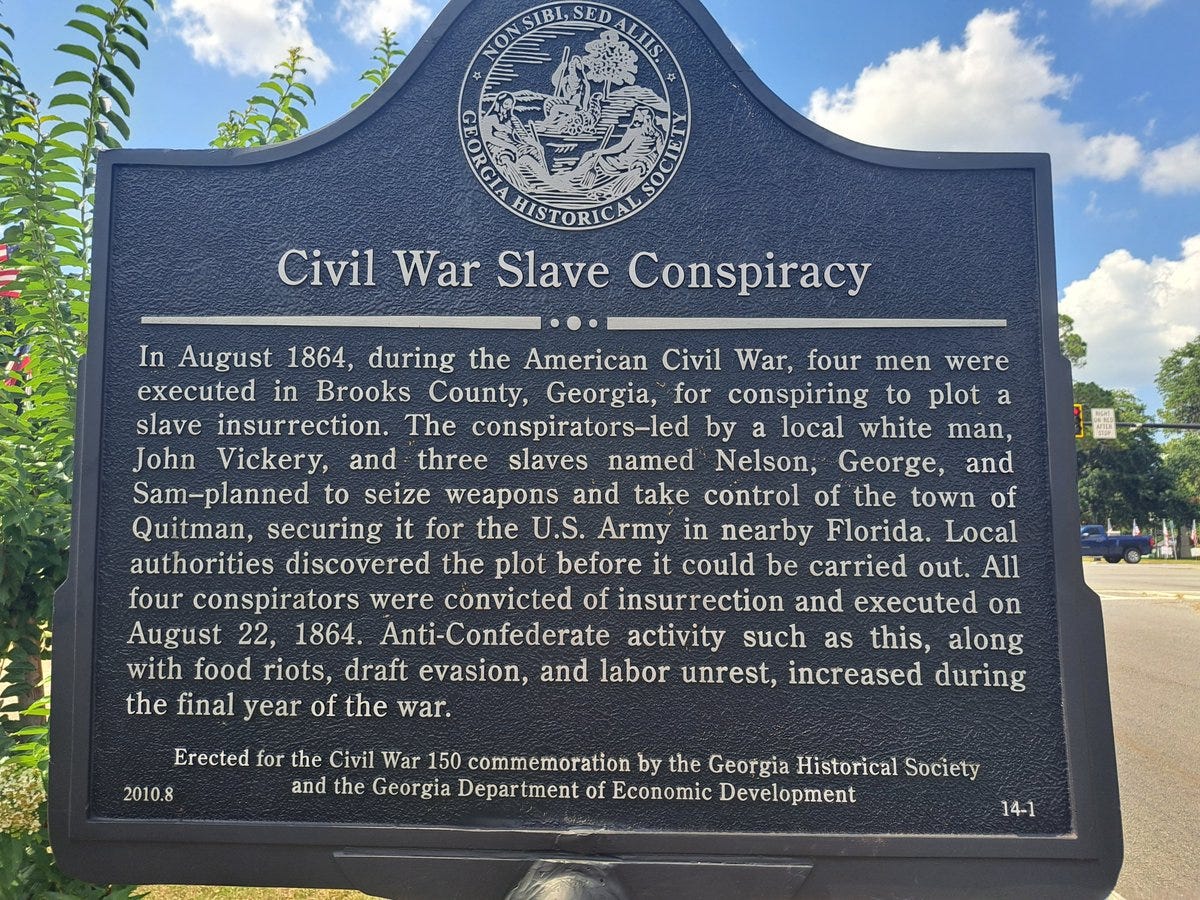

Enslaved people risked their lives, with little chance of success, to sabotage the Confederate war effort in places that were far removed from the Union army.

The Georgia Historical Society recently commemorated one such incident as part of its historical markers program.

Emancipation took place gradually and in fits and starts. As historians Jim Downs and Amy Murrell Taylor have shown, the journey from slavery to freedom was often accompanied by hardship such as starvation, disease and sexual exploitation.

By 1863 former slaves were serving in the U.S military and freeing tens of thousands of enslaved people by their very presence in the army. Over the course of the next two years they helped to liberate cities and towns across the Confederacy, including Charleston, South Carolina…

…and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

Consider Garland White’s account of entering Richmond on April 4, 1865. White had escaped slavery from nearby Hanover County before the war. His entry into Richmond with the 28th USCT also resulted in a reunion with his mother.

I have just returned from the city of Richmond; my regiment was among the first that entered that city. I marched at the head of the column, and soon I found myself called upon by the officers and men of my regiment to make a speech, with which, of course, I readily complied. A vast multitude assembled on Broad Street, and I was aroused amid the shouts of ten thousand voices, and proclaimed for the first time in that city freedom to all mankind. After which the doors of all the slave pens were thrown open, and thousands came out shouting and praising God, and Father, or Master Abe, as they termed him. In this mighty consternation I became so overcome with tears that I could not stand up under the pressure of such fullness of joy in my own heart.

Did enslaved people really need to be told that they were free in June 1865? No. If anyone needed to hear Granger’s announcement it was the white population.

African Americans had already embraced their freedom, beginning in 1861. They embraced it with their feet, their voices, in the uniforms they wore and the weapons they carried.

If Americans are going to mark the end of slavery on Juneteenth, we need an honest accounting of how it came about and the recognition that even all these years later we are still living with the consequences.

Happy Juneteenth! Andy Hall's website, Dead Confederates, has a bunch of interesting materials on Juneteenth and Granger in Galveston.

Thanks to Texas Republicans, it's probably illegal for Texas history teachers to explain the holiday in class.

“such fullness of joy” Wonderful thought. I hope when you finish writing your Shaw biography, you will write an honest accounting of how it all came about.