Paid subscribers should have received a zoom invite for Office Hours tomorrow evening at 7PM EST. It’s a chance to ask me questions and share your thoughts about recent posts or whatever else is on your mind about the history and memory of the Civil War era. Let me know if you didn’t receive the email. Hope to see some of you.

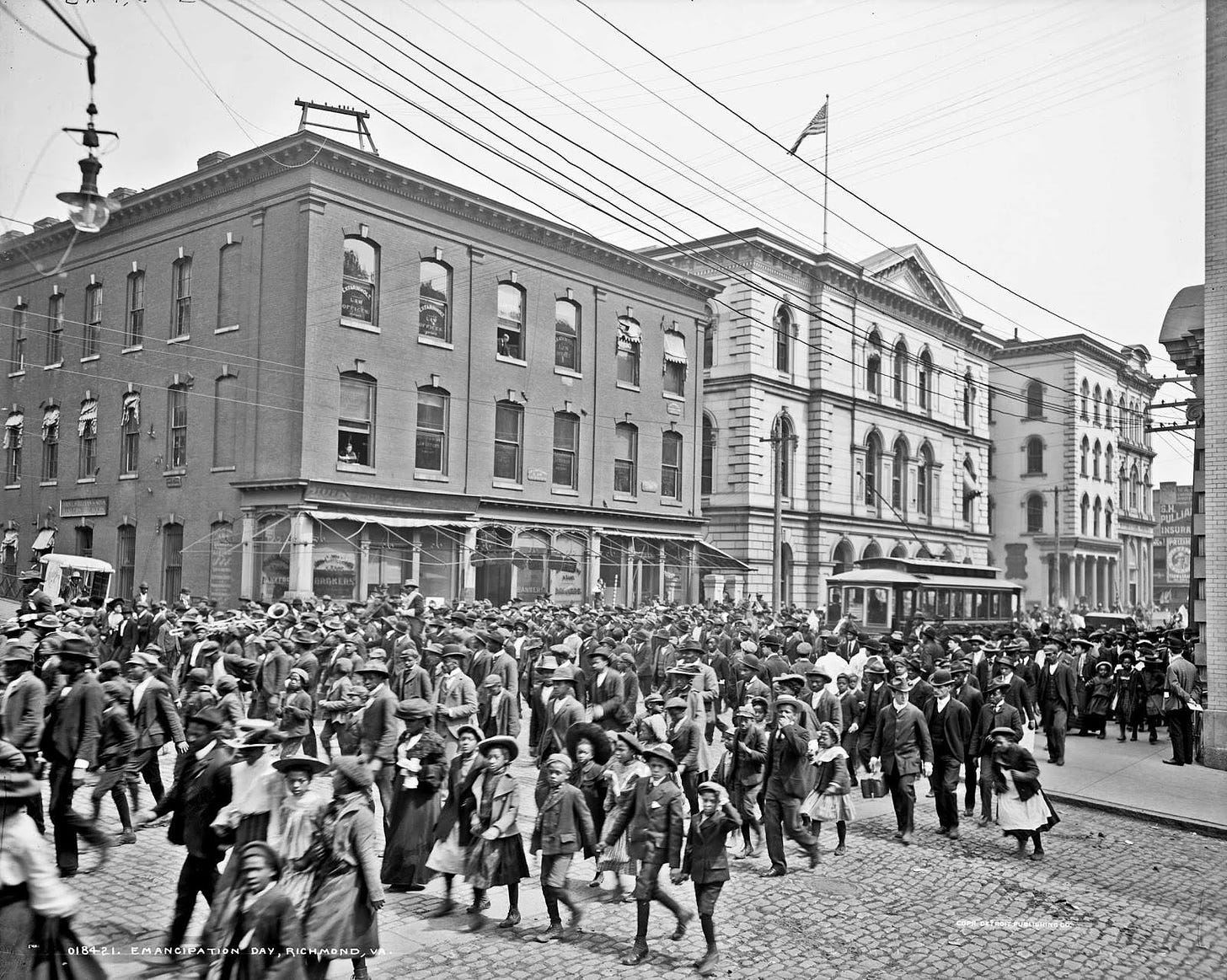

Today is the second year in which Juneteenth will be recognized as a federal holiday after President Biden signed legislation in 2021. As a federal holiday it is still in its infancy, but as a local holiday it has been celebrated primarily by African Americans since June 19, 1865, when Union soldiers under the command of Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas and read the Emancipation Proclamation announcing the end of slavery.

In The New York Times historian Tiya Miles shared her concerns about the holiday becoming overly commercialized.

With care and concerted effort, the Juneteenth holiday might rival Thanksgiving as a new communal ritual, highlighting the value of shared freedoms as our workweek tempo slows and personal rhythms align, even as we notice and cherish the treasure of each distinct celebration. In these right-size gatherings in parks, on blocks, at town greens and city squares, we can gain so much more than kitschy displays and logo T-shirts — loneliness dispelled, neighborhoods sustained and a torn national fabric slowly darned from the inside out.

For the sake of our history and maybe our country, we should let a thousand Juneteenths bloom.

I am more concerned that this day will remain a holiday that is celebrated almost exclusively by African Americans. At least that is what a recent Newsweek poll suggests.

Some 51 percent of respondents said they had no plans to celebrate, while 32 percent said they did and 17 percent said they didn't know.

Of those who had no plans to celebrate, a majority (54 percent) said they would not take part in a Juneteenth celebration even if they were invited to do so. About one-third (29 percent) said they would take part in a celebration if they were invited, while 18 percent said they didn't know.

The poll found 64 percent of respondents feel they ‘fully’ or ‘mostly’ understand the meaning of Juneteenth. Sixteen percent said they didn't understand it at all. A majority (59 percent) said they support Juneteenth being a federal holiday, while 12 percent oppose it.

It’s unfortunate that more Americans (especially white Americans) don’t identify with a holiday that marks the end of slavery in the United States in 1865, but that’s where we are given the intense politicization of history and history education.

My concerns stem, in large part, from the ongoing history wars on both sides of the political aisle.

On the one hand, Republicans and their allies on the right are committed to censoring the history of slavery and white supremacy through legislation that controls what can be taught and through book bans.

Their attempt to turn educators into enemies of the people has resulted in teachers across the country, who fear the consequences of teaching the history of slavery. Many of them will likely steer clear of discussing the history surrounding Juneteenth for fear of being reprimanded or even fired.

To get a sense of just how far Republicans have gone to shore up their base, presidential candidates Ron DeSantis and Mike Pence are now working to outdo Trump’s embrace of Confederate memory by promising to reinstate Fort Bragg after it was recently changed to Fort Liberty. Bragg owned over 100 slaves before the war and racked up one of the worst military records of any Confederate general.

For Republicans, honoring and remembering Confederate generals is more important than teaching the tough questions surrounding the history of slavery.

The left has also made it difficult for more Americans to fully embrace Juneteenth as their own and worthy of celebration. In his Juneteenth proclamation President Joe Biden suggested that, “Juneteenth is a day of profound weight and power.”

According to the president, it is, “A day in which we remember the moral stain and terrible toll of slavery on our country –- what I’ve long called America’s original sin. A long legacy of systemic racism, inequality, and inhumanity.”

Referring to slavery as this nation’s “original sin” is a problematic choice of words. It implies that racism and white supremacy are baked into the fabric of the nation rather than a learned behavior passed down from one generation to the next. Most importantly, it implies that we can do nothing about it.

Such language has become more common in an attempt to re-frame American history solely around the history of race and white supremacy.

Historian Johann Neem writes:

According to this extreme revisionist—and what I call post-American—perspective, we need an entirely new accounting of the past, not because the history we currently teach is incomplete but because all of American history is a lie. As post-Americans see it, this nation was founded on racism and is defined by racism. It is not just that America has a long history of racism. It is that America exists for, and because of, racism. It is a country for white people. White supremacy is its defining feature. The story of America was “stamped from the beginning,” in historian and activist Ibram X. Kendi’s words.

Our tendency now to reduce the founding of American history to 1619 weaves the legacy of this nation’s “original sin” through every aspect of its story in a way that obscures its complexity and the change that has taken place over time.

This historical reductionism minimizes substantive change in American history. Many people now insist that slavery really didn’t end in 1865; rather, it just morphed into a new form.

Such statement make a mockery of the accounts of former slaves, who themselves understood just what had changed with the defeat of the Confederacy and the end of slavery.

Historian Barbara Fields pinpoints the fundamental problem with the 1619 Project in this brief video excerpt.

Given this polarizing approach to American history it should come as no surprise that Black and white Americans have been unable to find common ground in a holiday that celebrates the end of slavery in 1865.

It’s unfortunate.

No one in 1860 could have predicted that slavery would be abolished in a few short years. As we all know there was nothing inevitable about the end of the South’s “peculiar institution.” Slavery had adjusted to an expanding and diversified economy well beyond the popular image of large plantation fields.

However we choose to explain the end of slavery—regardless of whether we take a long view or a short view centered on the war itself—at its center we will find an interracial coalition of unlikely allies.

The rhetoric behind the American Revolution inspired both Black and white abolitionists that would continue to push their agenda right up to and through to the end of the Civil War.

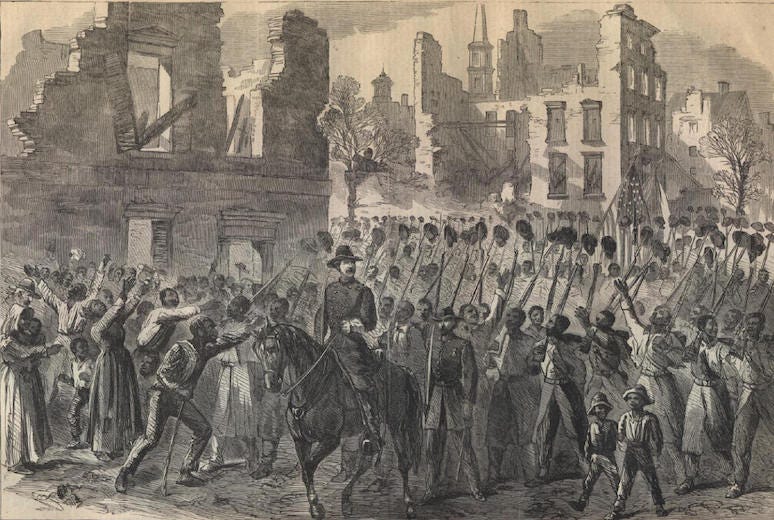

The Civil War itself led to a most unlikely coalition as a result of the contingency of war and military failure. From the very beginning enslaved people refused to accept that the United States was simply fighting to preserve the union. Their refusal forced commanders in the field, like Benjamin Butler at Fortress Monroe in May 1861, and eventually Lincoln himself to push for legislation that weakened slavery and steered the conflict toward emancipation by January 1863.

Many United States soldiers, who harbored racist views and who had little interest in fighting to free Blacks, were horrified by their first encounters with the violence of slavery and eventually came around to seeing its end as a combination of military, practical, and moral necessity.

By the middle of 1863 African Americans were volunteering in the thousands to save the Union and end slavery. Black regiments represented coalitions between white officers and the rank and file. Of course, these were always imperfect coalitions that were fraught with conflict. Many white officers embraced racist views and doubts about the ability of Black men to face the challenges posed by military life and especially the battlefield.

As I continue researching and writing about Robert Gould Shaw, I now see the young colonel as one linchpin in this uneasy and messy coalition that included his abolitionist parents on one side and the men in the 54th Massachusetts, who he chose to command for a number of reasons—most of which had little to do with his own abolitionist sympathies.

The history is complicated and messy. Like most revolutions it left many things unfinished. The outcome of the war raised the question of whether the United States could be re-imagined as a bi-racial democracy—a challenge we continue to face over 150 years later.

But one thing is for certain. The Civil War destroyed slavery once and for all. Regardless of the problems that continued to fester on the racial front for decades to come, it was never going to return.

If ever there was a holiday that should be able to bridge our political and cultural divide in this country it’s Juneteenth. The holiday highlights what is possible when groups embracing divergent and sometimes opposing goals find common ground around a shared cause.

Juneteenth should remind all of us of the hard work that still needs to be done on the racial front, but it is also a holiday that (dare I say) ought to leave room for a little national pride as well.

Kevin, I want to thank you for introducing me to Barbara Fields. When I taught American history i presented the origins of slavery much as she does, she does it much better. But many of my colleagues and students did not understand the arguments. They are rooted in the English adoption of industrial farming into what becomes British North America and as she said a need for labor in a place where just about anyone could acquire land. I think, as she points out, the roots do eventually take on significant racial overtones. But I realize this is not the point of your essay.

It is important for the country to acknowledge that we did grapple with and eventually end slavery. It is also important to acknowledge all that has happened since. The American world has changed since 1865 and mostly although not entirely for the better. Juneteenth should be, could be, a time to do that. This essay is excellent.

This WaPo article from Friday, June 16, is an excellent summary of Braxton Bragg’s career. “‘Bragg,’ Confederate officer William Dudley Hale wrote in a letter after the war, ‘was obstinate but without firmness, ruthless without enterprise, crafty yet without stratagem, suspicious, envious, jealous, vain, a bantam in success and a dunghill in disaster.’” His name was chosen for the new artillery camp because he was an artillery officer from North Carolina, and because his name was short. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/06/16/fort-bragg-renamed-fort-liberty-braxton-bragg/ I sincerely doubt that Pence and not-my-governor have any idea who they are defending.

Thank you for the link to Dr. Fields’ comments. I’ve often thought that, unless someone studies history post-high school and goes on to teach and write, most Americans are stuck with the simplicity of what they learned in fifth grade, slightly expanded in the higher grades if they had good teachers. I would include the majority of legislators at all levels. Our President, by contrast, met with Dr. Heather Cox Richardson https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/p/interview-with-president-biden

See you tomorrow evening.