I finally had a chance to watch the new Will Smith movie, Emancipation. It’s not a great movie, but it is well worth watching. For the purposes of this post today, I am going to confine myself to making a couple points that connect the movie to broader issues of Civil War history and memory.

The main character is based loosely on the famous Harper’s Weekly image of Gordon or “Whipped Peter,” whose scarred back shocked readers in the summer of 1863. There is much we don’t know about this individual. As historian David Silkenat writes:

The image of Gordon, his back scarred from whipping, remains one of the most visually arresting depictions of slavery. Based on photographs taken in Baton Rouge in April 1863, the image gained notoriety originally as a carte-de-visite (CDV), before being published as an engraving in Harper’s Weekly in a special Fourth of July issue that same year. The image illustrated to the Northern public and Union soldiers the brutality of the slavery. In the one hundred and fifty years since the image was created, it has become one of the most widely reprinted and recognizable images of American slavery, a common fixture in textbooks, university lectures, museum displays, and documentaries. However, despite the image’s ubiquity, we know relatively little about the image and the man featured in it. Most historians who have examined the image have accepted the narrative in the accompanying Harper’s article as an accurate account of the subject’s life and the image’s origins. This article argues, however, that there is good evidence to suggest that the accompanying article was largely fabricated and much of what we think we know about “Gordon” may be inaccurate.

The focus on the landscape of Louisiana throughout the movie, including its swamps and wildlife, offers a powerful argument for environmental history, which over the past few years has made its mark on the fields of Civil War history and American slavery.

A great place to start if you are interested in this literature is Silkenat’s new book, Scars on the Land: An Environmental History of Slavery in the American South.

The beauty of the landscape, as depicted in the movie, initially masks the brutality of slavery. Viewers eventually come to see it as both a road to freedom and, at the same time, as a barrier.

One of the things I was most impressed with is the movie’s depiction of slavery in the Confederate military itself. Most Hollywood movies set the institution of slavery on a plantation, as this one does in the beginning, but it quickly moves to the construction of a military railroad by the Confederate military.

Tens of thousands of enslaved men were impressed by the government to do this work.

This particular setting offers an important reminder that enslaved labor functioned as the “cornerstone” of the Confederate army and military operations throughout the South.

Every Confederate soldier, regardless of whether he owned one hundred or no slaves at all, was invested in maintaining slavery.

The setting also offers a sharp contrast with the way in which impressed slaves were depicted in the movie, Gone With the Wind.

During the evacuation of Atlanta and amidst all of the confusion of Federal shells and runaway carriages Scarlett happens upon former slaves from Tara, including “Big Sam”. He reassures Scarlett: “[T]he Confederacy needs it, so we is going to dig for the South…. [D]on’t worry we’ll stop them Yankees.”

Much of the movie centers around Peter’s escape from slavery in the military to the United States army, operating along the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge. The violence of slavery is pervasive throughout the movie, much of it in the form of a sadistic Confederate officer committed to tracking Peter down before he can reach the Union army.

Unfortunately, his Black companion, whose status is never clearly revealed, is little more than a distraction. Some viewers will be reminded of the character Daniel Holt from the movie, Ride With the Devil.

I also appreciated the way in which Peter’s escape complicates our understanding of emancipation in the South during the war. For far too long historians debated whether enslaved people freed themselves as opposed to Lincoln’s role through the Emancipation Proclamation and other federal policies.

We now know that the movement of the army played a key role in convincing enslaved people to attempt to free themselves.

Peter’s decision to join the First Louisian Native Guard and fight for the United States army completes his journey from slavery to freedom.

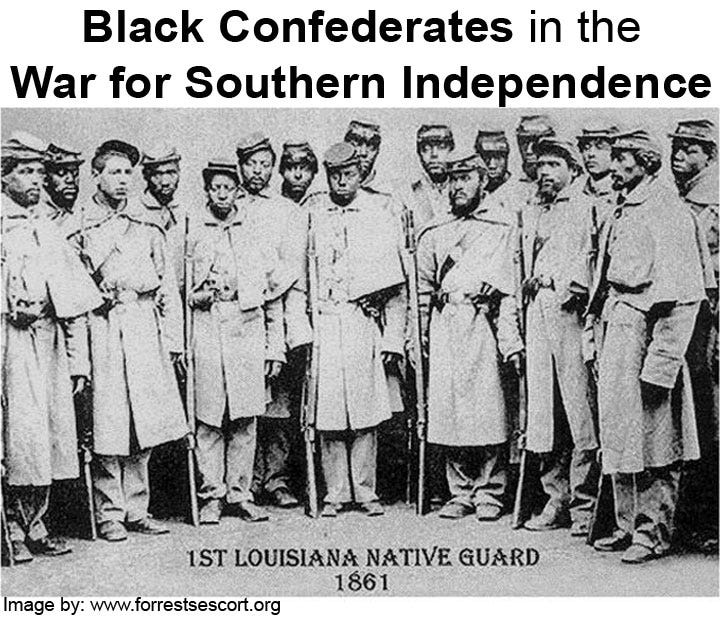

It was encouraging to see the LNG depicted accurately as a federal regiment as opposed to the many times over the years that it has mistakenly been referenced as a regiment of Black Confederates. This has long been encouraged by a photoshopped image of Black Union soldiers that was taken at Camp William Penn, near Philadelphia in 1864. You can still find it on hundreds of websites.

The scene depicting the battle of Port Hudson was done extremely well and might be the best battle sequence involving African American men fighting in the Civil War since Glory in 1989.

As I said at the top of this post, Emancipation is not a great Hollywood movie. Most of the characters are not developed in any significant way and the trajectory of the narrative is predictable. That said, I can see sections of this movie working extremely well in the classroom alongside other primary sources. The movie raises a number of questions for students to consider.

Finally, the movie reflects the ascendency of an “emancipationist” memory of the Civil War over the Lost Cause.

The movie was not bad, I'd give it a 7/10. But one thing I noticed that I had a question about (and please don't read this if you haven't seen the film):

In the Confederate slave labor camp, an enslaved man is shot and killed because he didn't listen to someone's orders. Granted, this is done to underscore the horrors of slavery and give one more reason for Peter to escape (as if there weren't enough already by that point). My question is, wasn't the enslaved man someone else's leased "property," to which you now have to explain that you've killed him? And wouldn't such an action likely make slaveholders less likely to rent out their enslaved people and do as much as they could to keep it from happening? I mean, even the heads on the posts might discourage enslavers from renting their enslaved to the Confederate military.

"I also appreciated the way in which Peter’s escape complicates our understanding of emancipation in the South during the war. For far too long historians debated whether enslaved people freed themselves as opposed to Lincoln’s role through the Emancipation Proclamation and other federal policies."

Peter is prompted to escape on hearing the news of the Emancipation Proclamation and that the escapes of Black people will be protected by the Union army, rather than turned away.

Personally, I don't see much value in the who-freed-the-slaves as much as as I see the two forces working together. Yes, I think it was a mistake to teach the history of emancipation without highlighting the agency of enslaved people themselves, especially with the many incredible stories of clever escapes. But I also think it's a mistake to understand emancipation while leaving out the actions of the Lincoln Administration, the Union Army, and career abolitionists. It doesn't have to be either/or.