One of the projects that I hope to return to in the new year is the editing of the letters of Captain John Christopher Winsmith. This is one of the best collections of Civil War soldier letters that I have ever come across in the archives. There are roughly 250 letters in the collection, but that’s not all. Winsmith went through the war as a “diehard Confederate,” but eventually joined the Republican Party in South Carolina during Reconstruction. He spoke out in favor of Black civil rights. One of his last letters was written to William Lloyd Garrison. This piece originally appeared in The New York Times in 2012.

In the spring of 1861 John Christopher Winsmith of Spartanburg, S.C., went to war with all the enthusiasm, determination and clarity of a member of the slaveholding class. Winsmith understood what was at stake, and he urged “the whole South to make common cause against the hordes of abolitionists who are swarming Southwards.”

The framing of the war in such stark terms not only reflected the region’s economic and political dependency on slave labor, but a sense of urgency manifested in the violent memory of Nat Turner’s 1831 insurrection and, more recently, the failed raid at Harpers Ferry led by John Brown. White Southerners convinced themselves that only outsiders could upset what they believed to be an organic, paternalistic master-slave relationship.

Thinking about subscribing as a paid member? Here is your chance to do so with a 25% discount for life. You will be able to post comments, gain access to the chat room and my new podcast series, as well as other exciting features that will be introduced in 2023.

OFFER ENDS ON DECEMBER 31. Happy Holidays!

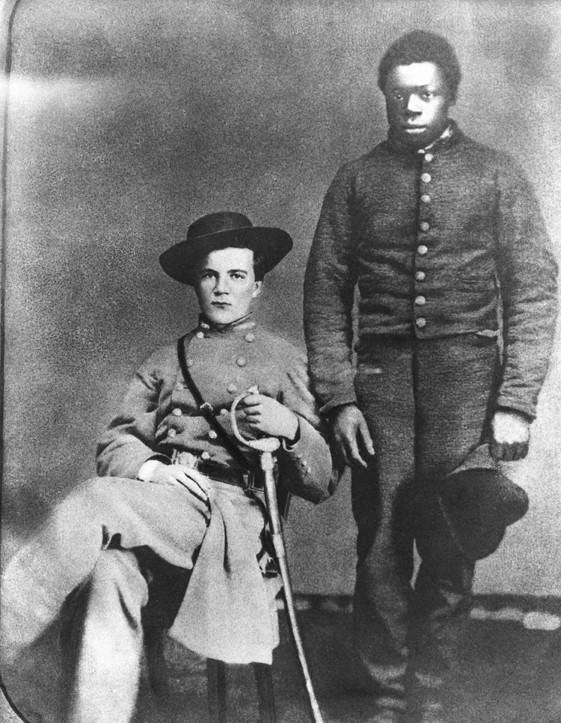

The Winsmith family, like other slaveholding families, expected their slaves to remain loyal and productive in exchange for a benevolent hand. Christopher, as he was known to his family, not only set out to defend this way of life, but he brought a piece of it with him — in the form of a personal body servant named Spencer.

During the next 16 months Christopher and Spencer remained side by side, moving from South Carolina to Virginia and back again. Although Spencer’s legal status never changed, the challenges associated with being away from home, as well as the exigencies of war, stretched the boundaries of the master-slave relationship to its limit. Their story fits into a broader narrative of the dissolution of slavery on a personal level and, ultimately, the defeat of the Confederacy.

John Christopher Winsmith was born in 1834 to John Winsmith, a member of the state General Assembly, and his wife, Catherine. At age 15, Winsmith attended the Citadel Military Academy in Charleston, but he did not graduate owing to poor conduct: in November 1851 he was brought in front of the college’s board of visitors for defrauding “a Negro woman by passing to her a copper coin covered with quicksilver for amount greater than its value.” One can only guess at the nature of this transaction, but it may have been sufficiently embarrassing to prevent him from reapplying when given the opportunity.

Dismissal from the Citadel, however, did not prevent Winsmith from pursuing a law degree at Charleston College, which he completed in 1859. Two years later, he left for war.

Both Winsmith and Spencer departed the family home of Camp Hill with heavy responsibilities, the former having been commissioned a lieutenant in Company G of the Fifth South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. While Winsmith learned the art of command, Spencer acclimated himself to his role as camp servant. Early in the war thousands of slaves followed their masters to war; their presence not only pointed to the social rank of their owners, but also satisfied the need to mobilize as much of the Confederacy’s population as possible in the face of a much larger enemy. Indeed, tens of thousands of slaves would be impressed by the Confederate government by the end of the war to work on military projects, often against the protests of their owners, who viewed the policy as a violation of their property rights.

In addition to ensuring that Winsmith’s quarters were kept clean, Spencer washed his master’s clothes, prepared his food, brushed his uniforms, polished his swords and buckles, ran errands, foraged and tended his horse. Among all these responsibilities, Winsmith noted, “Spencer has proved himself an excellent cook.”

While it is impossible to ignore Spencer’s instrumental value to Winsmith, the two likely found comfort in the shared experience of living away from loved ones. For Spencer, communication with his wife, Peg, and children took place through Winsmith’s letters, which regularly included a passing “howdye” or thanks for a recent package toward the end before signing off.

The emotional pain of separation for Spencer was most likely balanced to some degree by the experience of increased privileges. His responsibilities left him with free time to earn extra money, which he did by washing for other men in the company – an arrangement that Winsmith consented to and acknowledged: “He is making more money than any of us.”

Winsmith could have said no, of course, but one thing comes clearly through his letters: Winsmith trusted Spencer, and, in a way, vice versa. Spencer tended to Winsmith during a brief bout with measles, and was even on the receiving end of care when dealing with his own health problems. Spencer performed his duties admirably, and even continued them when Winsmith was assigned to serve on a court-martial trial in May 1861. Winsmith declared Spencer to be “the best servant by far in Camp.”

A reflection of Winsmith’s trust can be found in his decision to take Spencer along on picket duty while stationed in Northern Virginia in September 1861. Along with the rest of the patrol, Spencer “could see the Yankees moving about,” but he made no attempt to flee. A few days after returning from picket duty, Winsmith told his family that “I do not have any fears of his being deceived by the Yankees.”

Winsmith’s confidence in Spencer persisted through the first winter of the war and during their journey back to South Carolina in May 1862. By then Winsmith had been transferred to Company H of the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry and elected as its captain. The unit was first assigned to a Confederate force on James Island, just outside Charleston. Following the battle of Secessionville in June 1862, and as part of the organization of his new regiment, Winsmith spent more time away from camp, first to procure bounties for new enlistees and later to organize conscripts from the area around Columbia. This meant leaving “Spencer in charge of my affairs at camp.”

It was in Columbia where Winsmith learned that Spencer was “missing.” Writing to his father, Winsmith promised to provide additional details once he was back in camp, but he urged his father to send another servant as if assuming the unlikelihood of Spencer’s return. He learned little upon returning to camp in July:

He went out on Sunday morning the 20th in company with another boy from the Regt, having obtained a permit from Lt. Nesbitt to go for potatoes near River’s house, which is not more than ¾ mile from the Stono River, in which there were some Boats. They did not return, and their absence being reported to Maj. Duncan, he sent out several companies to scour the surrounding wood, but nothing could be seen of them, nor of any trace where the Yankees had been. It seems to be a doubtful point whether they went off to the Yankees of their own accord, or were captured. Most of the men in the Co. think Spencer was captured, as he took nothing away with him and went off in his shirt sleeves, and from his conduct nothing had occurred to make them suspect that he meditated on escape. The watch, which he wished to take, was a galvanized one. I hear, that he had bought it in town, and wanted to dispose of it as I had told him he would go home soon. He brought all my things over right when our Regt moved, and I have missed nothing. If he was captured he will very probably make his escape at the first opportunity.

As that last sentence indicates, Winsmith struggled coming to terms with Spencer’s sudden and unexpected disappearance, even going so far as to suggest that his partner had “persuaded him off after they left camp.” He would consider any number of explanations but for a desire on his part to be free. Finally Winsmith comforted himself by falling back on the common stereotype that, “negroes are very uncertain and tricky creatures so it is difficult to tell what is the real truth in this case.”

The loss of Spencer tugged at Winsmith’s emotions, at least at first. “You may know I miss him very much,” he admitted to his father, “but I will not let the matter worry me in the least as I know it will do no good.” Winsmith’s sincere feelings of loss, however, did not overshadow the instrumental role that Spencer had played in his life, and in short order he pressured his father to send along another slave. By the beginning of August, Winsmith had “nothing more to write” about his former servant.

One of the many tragedies of slavery is its legacy of illiteracy and the lack of a substantial record that gives voice to slaves such as Spencer. In this case, as in so many others, we are forced to rely on brief references from the man who claimed legal title to him to discern what he thought of his own condition. Unfortunately, we know precious little about how Spencer experienced the war. The most we can say is that Winsmith, for all his claims to “know” Spencer, understood very little about him.

UPDATE: Just to be clear, when I reference Spencer 'following' JCW to war I am doing so fully aware that the master-slave relationship was defined by coercion. Spencer had NO choice but to accompany JCW.

Good story. Even the most self-proclaimed benevolent slave owners couldn’t understand the desire for freedom. It is a shame we don’t have better accounts from those who accompanied their owners as servants and laborers. Their stories, and what the war meant to them, would be fascinating.