There was nothing inevitable about the way our Civil War monument landscape emerged by the early twentieth century for the same reason that there was nothing inevitable about the rise of Jim Crow and legalized segregation.

I sometimes wonder how our Civil War monument landscape would have evolved had it reflected the collective past and values of the majority of towns, cities, and counties across the South at this time. But it didn’t and we know why.

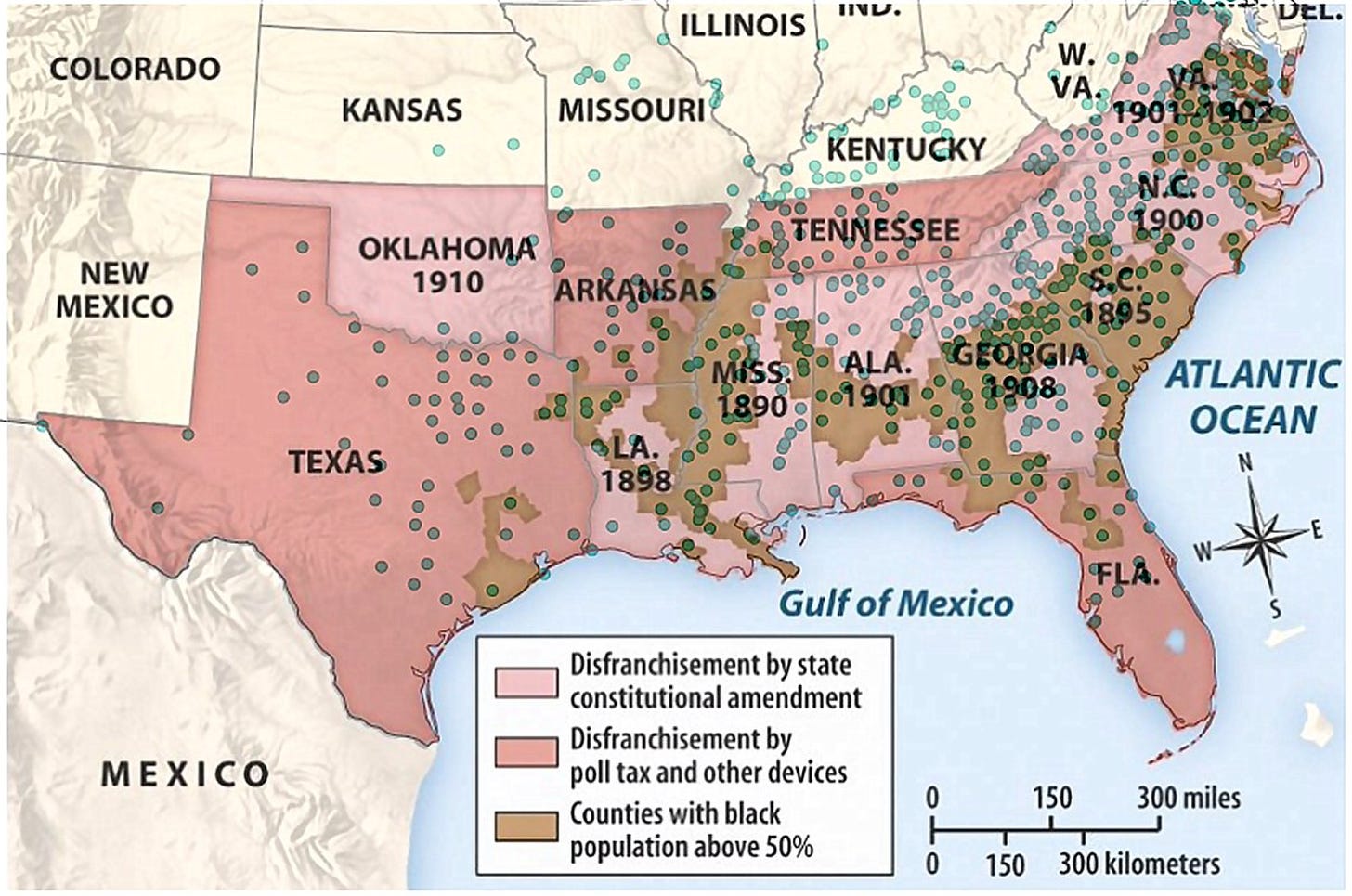

I’ve used this map many times before because it’s very instructive.

Monuments reflect the shared memory and values of those members of the community who enjoy political power or have access to the wheels of local government. By the beginning of the twentieth century most African Americans had lost the right to vote and run for office as a result of new state constitutions and rampant violence throughout the South.

Just consider all the Confederate monuments that were dedicated during this period in counties where African Americans were the majority. As I have pointed out before, the problem isn’t that Confederate monuments no longer reflect the shared past and values of the majority of many communities throughout the South. The problem is that in many places they never did.

Thankfully, this is beginning to change. The removal of monuments should and has been accompanied by the dedication of new monuments. Over the past few decades this has taken the form of monuments and markers honoring United States Colored Troops.

Let’s put this in perspective.

Before the dedication of the African-American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1998, only two monuments commemorated the service of Black Civil War soldiers. The first was the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Massachusetts Memorial dedicated on the Boston Common in 1897. In 1920 a statue of Sergeant William H. Carney, who served in the 54th and who earned the Medal of Honor for gallantry at Battery Wagner, was dedicated in Norfolk’s West Point Cemetery.

Ask yourself how many monuments honoring African Americans and emancipation could have been dedicated in the areas shaded in brown on the map above during the height of Civil War monument dedications across the South. Instead, a commemorative landscape emerged that erased and/or mythologized the history of African Americans by reducing them to “loyal slaves.”

History and memory came to serve the interests of white Southerners in the maintenance of white supremacy.

Since 1998 and especially over the past 15 years we’ve seen a number of new Civil War monuments that honor Black Civil War soldiers. In October of 2021 a statue was dedicated in Franklin, Tennessee.

And just this past weekend a statue was dedicated in Clarksville, Tennessee. Make no mistake, these new statues reflect changes in the racial profile of local government and the ability of local citizens to work for change—many of whom were prevented from doing so in year’s past.

Just as there was nothing inevitable about the emergence of our Civil War monument landscape in the twentieth century, there is nothing inevitable about its future. As we have seen over the past few years Americans, who were once prevented from shaping the monument landscape owing to legalized racism, now have the power to do so.

Perhaps we are only now moving closer to where our Civil War monument landscape more accurately reflects the collective history and values of communities across the country. Perhaps we are only now moving closer to what it always could and should have looked like.

Thanks for a great post. For a while, I was wondering if we were losing history when the monuments came down. Now it seems we were losing a history that never happened.

Hope this will put the kibosh on the dishonest argument that removing statues is erasing history. Of course, removing a statue of e.g. Jefferson Davis does nothing to remove the harmful marks he left on the USA or the histories describing them.

Better argument, however, is that removing some statues is removing some lies about American history. That's an argument worth having.