One of the things that I am fascinated by, in my researching and writing about Robert Gould Shaw, is the extent to which his understanding of slavery was transformed as a result of his extended service in Maryland and Virginia in 1861-62. Like many of his fellow Brahmin officers in the Second Massachusetts, Shaw had no direct connection to the institution of slavery before the war.

His wartime letters home and those of his fellow officers are filled with stories about interacting with the enslaved, especially individuals and even families seeking freedom. Regardless of their embrace of abolitionism before the war, it was this direct contact that played the most important role in convincing many that slavery needed to be destroyed along with the Confederacy.

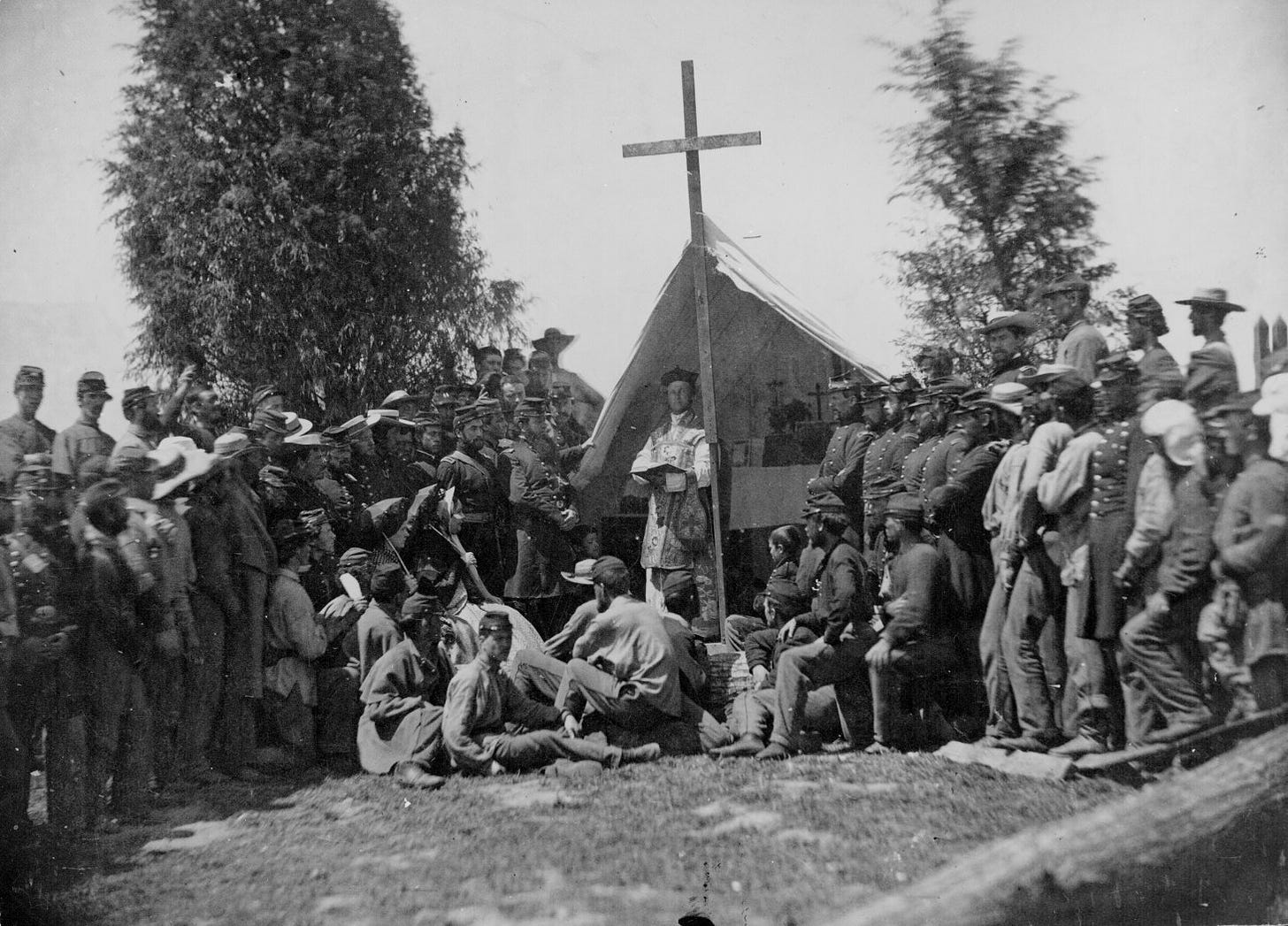

A really interesting example of this transformation can be found in the correspondence of Alonzo H. Quint, who served as the regimental chaplain.

Quint was born in Barnstead, New Hampshire on March 22, 1828. He graduated from Dartmouth College in 1846 and went on to study medicine, but left early to enroll at Andover Theological Seminary in 1849. He remained at the seminary for one year after graduating in 1852. Quint became the pastor of the Mather (Central) Congregational Church in Jamaica Plain (now part of Boston), just a stones throw from where I currently live.

On April 5, 1862 The Congregationalist published a letter from Quint that had been written just weeks earlier while the Second Massachusetts was encamped in Winchester, Virginia. The First Battle of Kernstown was about to be fought—the first of many engagements against Confederate forces under the command of Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson that would become known as the Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

The letter focuses on Quint’s growing disgust for slaveholding ministers and slavery generally.

The Gospel hereabouts is set in a pro-slavery frame. Ministers occasionally own their fellow beings. I used to think that I would admit a brother minister into my pulpit careless of the question whether he were a slaveholder or not. I would not do it now. I will not say that there are not many slave-owners who are Christian; I know some whom I do respect and love; some who labor and pray for the conversion of their slaves as those for whom they must give an account as the day of judgement. But a slaveholding minister—I could not endure that.

I am no fanatic. I never even voted a Republican ticket. I would treat tenderly those thus perverted. But this eight months’ campaign on slave soil, in localities where slavery assume its mildest type, has made me feel—and I do assure my conservative ministerial brethren—that the whole system is infamous.

‘The sins of slavery’? there are none: it is slaveholding itself that is sin. Its effect on the masters is one of its greatest evils; it perverts the conscience, warps the intellect, brutalizes the heart. Believe no such nonsense as that ‘the slaves are contented.’ They, with no noticeable exception long to be free. Nor is there any difficulty in settling the slave question so far as our armies go. The property is thenceforth good for nothing. Crowds of blacks forsake their masters at the first opportunity. In this very place, over and over again, do they say, ‘I have worked so many years for my master, now I want to work for myself.’ They are docile, peaceable and industrious. They say, ‘only hire us, and try us.’ Can it be that Government means to remand these now happy fugitives to their oppressors? As any army we have nothing to do with slavery. We neither entice, nor drive back. The blacks take care of themselves.

I was amused with one case at Charlestown. A master refused to sell any chickens, even ‘because,’ said he, ‘I must feed my poor servants, who will never leave me;’ and he wanted a guard over his property. In a few days his ‘poor servants’ were all gone, and this aristocratic son of one [of] the ‘first families of Virginia,’ was himself taking care of his solitary cow and pig.

Quint’s observations fit neatly into the free labor ideology embraced by so many Northerners. He described them as “industrious” who yearned to work for themselves. The letter also reveals the ways in which enslaved people themselves helped to shape wartime goals. The very presence of the army allowed African Americans to “take care of themselves,” or assume some control of their own destinies by running away from their masters in search of freedom.

The Valley Campaign continued to undercut the institution of slavery in the region. I am still thinking through the extent to which Shaw’s time in the region impacted his thinking about slavery and emancipation, but there is no question that it was as important, if not more, than anything he learned from his abolitionist parents before the war.

Think of the change in the Army of the Potomac that was devastated when Lincoln fired McClellan in November 1862 then voted overwhelmingly for Lincoln over McClellan in the presidential election two years later. McClellan of course detested the Emancipation Proclamation and was probably right when he told Lincoln the Proclamation was very unpopular with the soldiers when it was issued. But two years of moving south, experiencing slavery and freeing slaves, convinced them that Lincoln was right on this issue, and McClellan was wrong.

"....perverts the conscience..". Good read. Thanks for sharing these thoughts.